After my months in Berkeley, I flew to Chicago in late

October or early November 1969. I

visited for a few days with Jeremy Gladstone (a friend from Knox College) who

was back from Europe and staying at the family home in Park Forest until he

sorted out his next move. In Europe

Jeremy had acquired a taste for Pernod, one of the anise-based French liqueurs,

a legal form of absinthe. He showed me

how to drink it over ice, with water.

One evening he

invited a group of former Knox friends, and initiated them as well. I’m pretty sure Howard Partner was among

them. We sat around a table drinking

Pernod. I think it was on this occasion

that I got a better appreciation for how far apart these Chicagoland suburbs

really are. It took longer for everyone

to get there and to get back than the time we spent together.

My next stop was the family home in Greensburg. This was likely a short visit because I was

soon on my way to rejoin Joni in Connecticut.

I got myself there by first going to Washington for the second

Moratorium demonstration against the Vietnam War on November 15. This turned out to be officially the largest

Washington demonstration of the war. I

may have gone down with my friend Mike or maybe I met him there because he was

stationed nearby. He had been drafted

into the Army the year before. So I

marched against the war in the company of an active duty soldier (or in his

case, chaplain’s assistant.)

Many demonstrators from distant places came on rented buses,

and so my plan was to find a bus returning to New Haven and hitch a ride. Not

really a mad strategy in 1969.

In any

case, the plan worked. Mike and I found a bus going to New Haven and they had

empty seats.

I even got acquainted with

someone on the bus who offered to put me up for the night when I couldn’t reach

Joni upon our arrival.

In the morning I

met his wife, and he and I traded versions of Dylan’s “Girl From the North

Country” (I knew the Nashville Skyline version in G, he knew the original version

in C.) Then I called Joni again and she came to pick me up.

Joni had found a small place in a village called Stony

Creek, directly on Long Island Sound, about eight miles from New Haven. As I recall, it was three rooms in a

building set back from the main drag, Thimble Island Road. Though oysters and lobster fishing were part

of its identity, the “stony” in Stony Creek likely came from the quarry. Before it closed at the beginning of the 20th

century, it supplied pink granite for the Brooklyn Bridge, Grand Central

Terminal in Manhattan, and the base of the Statue of Liberty.

With a population of about a thousand, Stony Creek was part

of the town of Branford, Connecticut.

An article I clipped from the New York Times a decade later began with

the quip of an unnamed critic: “Every town has its village idiot, but only

Branford has an idiot village.” This

article made much of Stony Creek’s resistance to change; specifically to

tourism. I don’t know if it’s still

that way, though photos on line don’t give me that impression.

The 1979 Times article suggested that many residents were

employed at Yale, and perhaps that was the case to some extent also in

1969. Across the Sound from Stony Creek

there were houses where groups of Yale Law students lived. One of them was named Bill Clinton. His

girlfriend Hillary was often around.

Joni’s brother-in-law was at Yale Law, and she attended a party over

there sometime before I’d arrived.

Perhaps they met.

I don't know if it was a cultural high point but in the late 1930s, Stony Creek had a summer theatre, operated by two women who also interned for the legendary Mercury Theatre in New York, run by John Houseman and Orson Welles, often the star in its productions. This is how Stony Creek hosted a Mercury Theatre show for a week prior to its Broadway debut. Unfortunately the tryout was so dismal that the show never opened--only those who came to Stony Creek, like Katharine Hepburn, ever saw it. She stole one of the actors, Joseph Cotton, for her 1939 Broadway hit, The Philadelphia Story, which revived her career.

That New York Times article sings the praises of Stony Creek in summer, but

I saw it only in the dead of winter, intermittently from November through

February (with some time back in Greensburg for Christmas, which extended well

into January to avoid Joni’s parents, visiting her and her sister. They were not my allies.)

|

| BK |

Still, even though it was dim and frigid (or sunny and

slushy) much of the time, I liked our corner of Stony Creek by the Sound. The Sound wasn’t the ocean but it

was something, and it was always there.

I wrote this about it:

Dredging the gray sky,/the winter wind sears home./Against the window/it pours/stinging rain from the

sea./Though it does not leap into the warm kitchen/I go out to meet it/greet

it/say hello/and come back in.

Something about that dynamic suited me then, and still does.

Besides the Sound, there was very little else in Stony Creek, at least within

walking distance, except farther down Thimble Island Road there was a small

store--and a public library. It was

(and is) the Willoughby Wallace Library, built in 1956 thanks to a bequest by

the eccentric but public-spirited Mr. Wallace, plus an architect’s donated

design, and donated town granite.

So this bright substantial building was pretty new when I

discovered it, amazed it was there.

I

was inside it just after 3 in the afternoon, and found it was a prime hangout

for high school students after school.

They sat around sunny tables, munching candy from the store and

debriefing the day: who got in trouble on the bus that morning, who got ripped

last weekend, plus demonstrations of how Martha and Jennifer walk. (As well as

casting suspicious glances at the possible narc with the long hair, taking

notes.)

Around 4, they were replaced by a noisy bunch of grade

schoolers. “I wonder what menstruation

means?” I watched a third grader look

over a Jimi Hendrix album. Others

laughed over the magazines, or broke into whispery, gossipy groups.

The library became my regular destination—walking past the

abandoned offices of Pacific Sanchero, Permittee, and the house with the

multicolored design painted by a summer tenant, who also inscribed on its wall

“Latch onto a feather.” In relatively

good weather, I could sit on a stone bench outside, if it wasn’t already

occupied by the aforementioned students.

It was in this library that I discovered an author I would

follow for the rest of his life: Ronald Sukenick. Very likely his latest book

was on display, with a title bound to catch my eye: Death of the Novel and

Other Stories. (The “death of the

novel” was a thing, long before—and much different than-- the death of the author.)

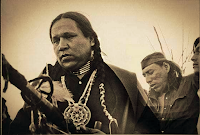

|

| Sukenick |

The stories amazed me—I hadn’t read anything like them

before. Today some might qualify as

“metafiction,” or be called deconstruction.

At the time they felt to be attempts to find new forms commensurate with

the current fractious and fractured reality, as well as further forays in

expanding the possibilities of writing by essentially playing with some of

those possibilities. These stories were

basically comic, and in a sense conventional—the experiments were part of the

story, as for example, when he includes a transcript of a conversation with his

wife with a tape recorder between them.

When the conversation becomes uncomfortable for him, he wants to turn

the tape off. (At least that’s how I

remember it, from a re-reading ten years ago or so.)

So I was delighted to find in the library stacks a copy of

his novel, Up, published the previous year. It also played with narrative—the initial character was a writer,

so part of it is about a character he’s writing (Strop Banally), including the

changes he’s making along the way (the character’s hair color, etc.) It also threads other narratives, but again

includes critiques of their discontinuities and excesses as part of the story.

Sukenick seemed only a little older, and I immediately

bonded with our similarities in outlook and literary attempts, ignoring many

differences. Writing conventional

narrative seemed superficial and false to many in those nuclear psychedelic

Vietnam Nixonated days. I didn’t get

all he was doing or trying to do, but I was attracted to the mosaic form and

the irreverent style I’d been drawn to in the Beatles, Vonnegut, Donleavy,

Joseph Heller, etc.

|

| My Sukenick collection, minus "Mosaic," hiding somewhere |

But Sukenick became a hard author to follow—even as a

reader. Those first two books were from

major publishers, but subsequent ones were from small presses, including the

organization he helped to start, the Fiction Collective. At least a few times I found his books on

carts of university bookstores sale books.

I found his 1986 novel

Blown Away (Sun and Moon Press) deep in a

pile of discount books on my last visit to the Harvard Coop bookstore. But I managed to get copies of all of his

novels, and one collection of stories.

I still have most of them, including his last, easily the best fiction

I’ve read about 9/11,

Last Fall.

I even have his extremely useful book on Wallace Stevens,

Musing the

Obscure, from his earlier life as a very perceptive and methodical literary

scholar. He died in 2004.

Sukenick was a named character in Up, and the novel

followed other characters (his boyhood friends mostly) who also were a little older than me. There were retrospective scenes from their

past, though I wasn’t much interested in them at the time. (Now they seem

vivid.) What impressed me was that this was contemporary fiction about contemporary

times and people. Characters smoked

dope and talked about revolution (though usually their complicated reasons for

supporting it and not supporting it simultaneously.) They were out of school (though some were teaching) and trying to

find a place in a society they feared and loathed. That got my attention, as I

was just beginning that journey.

When I wasn’t in Stony Creek, I was in New Haven, a 20

minute bus ride away. My efforts to

find a job—desperate, muddled and halfhearted simultaneously-- were focused

there. I checked bulletin boards and the newspapers, including the Yale student

paper.

In one of those papers I saw an ad for volunteers for a Yale

psychology department experiment “in learning” that paid $25 for a few

hours. I called the number and asked

for more information on what this experiment entailed. My first suspicion was that it involved

drugs, and at this point in my life I wasn’t eager to let others experiment on

me. The female voice on the other end assured me there were no drugs but when I

asked other questions she was persistently evasive. That turned my suspicions

into alarm bells. As much as I needed

the money, I didn’t participate.

Years later I realized that this was very probably an early

iteration of the famous (or infamous) Milgram experiments. (This was pretty

much confirmed for me in a book by psychologist Elliot Aronson when he

described what subjects were told the experiments were about—precisely what

that ad said.)

The Milgram experiments were one of the most often cited

psychology experiments of modern times.

Participants were instructed to give electric shocks to people in the

next room if they answer questions incorrectly. With each wrong answer the shock is intensified, until the victim

can be heard screaming in pain and begging to be released from the experiment.

The victims weren’t actually getting shocks—they were in on the con. The experiments weren’t about learning; they

were to see how many people will follow instructions and administer the shocks,

even after hearing cries of pain and the begging.

The answer was a shockingly high percentage of them. I first heard it reported as 100%. Later the figure given for those willing to

administer the maximum voltage was 64%.

The experiment is usually said to prove two main points: that people

will do what authority tells them to do, and that people will do so in

situations even if they believe that they wouldn’t, regardless of their

personal ethics.

But here’s the problem.

To make such an inference about people in general, the participants had

to accurately represent the population.

This is the fatal flaw of most such psychological experiments

(participants are mostly students who always need money, and overwhelmingly

white.) In this experiment, those who actually participated had to be willing

to take the unquestioned word of authorities, without knowing what they were

getting into, just to walk in the door. So they were self-selected

pre-disposed. But how many people like me smelled something fishy and just

didn’t participate? On the other hand,

how many participants needed the $25 enough to do what they were told?

Think about it: this was Yale in 1969 and 1970. There were antiwar protests on campus. William Sloane Coffin, an advocate for defying

the draft and therefore the authority of the government, was a campus

hero. Part of the huge generation gap

was the distrust many younger people had for the honesty and veracity of those

in authority in the government, the university

and big business. Scientific

research secretly funded by the military was a big issue on many campuses.

So if you were against the killing and the maiming in

Vietnam, to the extent of resisting the government’s orders to do so, or even

if you were a stoned peace and love hippie, how likely is it that you were

going to push a button to cause somebody pain?

I’ve seen photos of these experiments—there was no long hair, no

countercultural clothing in any of them.

(These experiments, now considered unethical, are often cited

along with the equally notorious Stanford

experiments that purported to prove that people given the role of prison

guard invariably act in sadistic ways towards prisoners. This was a much-cited finding in the

corporate world of the 1980s and 1990s, though the experiments have largely

been discredited.)

My perspective on the Milgram experiments led to my

skepticism of many psychological experiments, and books about them. I found support in the work of eminent

psychologist Jerome Kagan, particularly in his book

Psychology’s Ghosts: The

Crisis in the Profession and the Way Back, in which he gently but

definitely

questioned whether universal conclusions about behavior can be based

on small numbers of culturally identical subjects in a laboratory setting.

In any case, the stark divide in the late 1960s was

something I keenly felt. Even before

the Pentagon Papers or Watergate, there was amply evidence of systematic lying

in high places. All our literature,

movies and music questioned the moral authority if not the intelligence of

those running things. Apart from my

ignorance of how the “adult world” worked, and how I could possibly find my way

into the elements of it I still respected, my general attitude was both baffled

and adversarial. How could I make a

living, and not lose myself? I had too

much yet to learn.

“Out of college, money spent,” went the Beatles’

lyric, “see no future, pay no rent/all the money’s gone, nowhere to go. But oh that magic feeling/ no where to

go...”

Apart from visits to my Knox friend Mike Shain, who for some

reason now forgotten was living in a New Haven rooming house, with a sign on

his door that said “Home of the Bobby Dylan Conspiracy,” I gravitated towards

Yale. The academic campus was still the only industrial site I knew, and where

I was somewhat comfortable. I went to

readings and knew how to get myself invited to the parties afterwards. I believe that’s where I heard poet Kenneth

Koch read.

He read a long poem that may have been called “Eyes.” In any

case, it was my inspiration for a long poem I later wrote called “Ears,” which

was published a couple of times in the mid-70s.

I heard the poet

Bill Knott, who at the time was writing under the name of St. Geraud. I was astounded by his poems—they were the

most unrelenting and mind-blowing surrealist poems I’d encountered. Also very

short. He may have read on the same

bill with Koch or perhaps another poet, because I remember him being at the

after-party and he left without much notice. Later I happened to be in the

living room of this house when the doorbell rang and I answered it. It was Bill Knott, looking shamefaced about

returning. I laughed. I loved it.

I met poet Michael Benedikt and we began a correspondence

when he was back in New York. He was interested

in my writing that I sent him. This was some rare encouragement. I was still sending things out and getting

them back.

Thinking back, it seems obvious that this would have been a

good moment for a mentor to appear in my life. But it didn’t happen then, and

never happened. I later depended

greatly on the faith of several editors, but they were all more or less my

contemporaries. This, like everything

else, was as much my fault as anyone’s, and equally a sign of the times.

I did manage a fair amount of writing at Stony Creek. Apart from verse and short fiction, and the usual endless

notes on the novel I wasn’t writing, I once simply let go and wrote a sustained

prose fiction called “Apostrophe S.”

Influenced by Sukenick but more by Vonnegut in its tone, I wrote it late

at night, in the warm quiet kitchen, while Joni was asleep. I often had the

company of our two kittens, named Abbey and Rhoda, who prowled around the pale

plywood plank I was writing on, and chased my pen across the yellow legal pad.

What survives of “Apostrophe S” seems to include elements

added later. Perhaps a wise editor

could have helped me develop the good parts (some were quite funny) into

something publishable, but in retrospect, the best part of it is remembering

the experience of writing it.

But I did write something while at Stony Creek that was more

of an indication of a direction I would later follow. It’s not much remembered, but in late 1969, there was a brief but

intense frenzy over an assertion that Paul McCartney had died in a car crash

some three years before, and been secretly replaced by a lookalike. Then the Beatles had seeded various songs

with clues. This “Paul is dead” theory

led to top 40 stations all over America airing the “evidence” as well as lots

of Beatles songs. It made the news

(Huntley-Brinkley, Time Magazine) and a New Haven moviehouse advertised a

special showing of Yellow Submarine with the line, “Paul is alive and well in

Yellow Submarine!” Sales of Beatles

albums shot up.

But what apparently impressed me most was how seriously the

high school students I saw in Stony Creek were taking it. I realized that this was a contemporary

subject of interest to my generation and younger that I knew something about,

both in terms of the Beatles and what are now known as “conspiracy

theories.” The long piece I wrote about

it, entitled the “The Paul Is Dead Theology,” was the kind of cultural

reportage and analysis that in the not too distant future I would be writing

and publishing. But at that moment,

though Michael Benedikt especially liked it and tried to get it published, it

only joined my manuscript pile of futility.

The article asserted knowledge concerning what high school

students were talking about that I probably didn’t derive just from hanging

around the Stony Creek library. Joni

was teaching high school, and we talked about her students.

We had happy times in Stony Creek. The music I associate with those wintry days includes the Band albums and The Papas and the Mamas, especially the song "Safe in my Garden." But our garden was not so safe. Our

problem was the future, and the nature of our future together. These issues

were the sources of tension, and along with external and internal pressures,

were more than an undercurrent to those months. But as far as I knew we’d come to no conclusion.

|

| Stony Creek sunset. BK photo. |

Apart from manuscripts, I’d sent out various proposals,

applications and inquiries. I applied

for a summer arts workshop at Cummington, in western Massachusetts. I was in touch with Knox friend Steve Meyers

who was in graduate school in Buffalo.

He was enthusiastic about the English department there, and urged me to

come up and check things out. Perhaps I’d come to the reluctant conclusion that

I didn’t know how to do anything that paid a salary except maybe teach, and if

I was going to have to make a living that way, I would need an advanced

degree. Or maybe I was just looking for

some income for a few years, burrowed into books.

So one cold March morning I slid a duffel bag and my guitar

case into the front trunk of Joni’s yellow VW bug. We drove first to the dump

in a frozen field of thin snow, and I unloaded a bag of garbage. I got back into the car and she drove me to

an interstate ramp, so I could begin hitchhiking up to Buffalo. After a brief farewell, she drove away. It would be the last time I saw her.

Shortly after I got to Steve’s in Buffalo, her letter

arrived inviting me not to come back.

Over the next weeks we talked on the phone a few times and exchanged

letters, but the situation didn’t change.

I was dislocated and bereft on many levels, but I don’t think I really

blamed her. I certainly saw the justice of her point of view.

If Sukenick’s Up has a theme it would probably be to

“be true to the discontinuity of experience.”

Even then, the 60s seemed an especially discontinuous and contingent

time, so it seemed writing should express it.

But discontinuity is also a theme of youth.

All experience that falls outside the expected, the changes and rapid

twists and turns, especially when moving among “worlds” of what passes for the

traditional or normal and what seems to be new, as well as crossing undefined

geographical, socio-economic (class) and other borders, is experienced as

discontinuous. It’s only later that

it’s possible to sense the patterns, the continuities, even if they never

become entirely clear, or they are multiple.

There may be accidents or missed opportunities or stupid

moves and so on, the memory of which may keep us up at night, but ultimately

they become elements in the pattern.

For example, had a certain letter arrived a few days earlier when I was

in Berkeley, my life might have taken me in a different direction, perhaps to

western Canada. And so on. Or as we said a lot in those days, so it

goes.

In a way that’s what this project is about: partly through

the agency of reading, seeing where things fall into the pattern that time has

made, that can only be seen retrospectively.

In a larger sense, that’s a project of old age.

Events of all kinds contribute to the pattern—things that

happened and did not happen, as well as things read or thought or felt or heard

or seen, or desired, or feared. The influence of others at a particular time,

or the lack of it. The picture will never be complete, because memory and

various kinds of records of the time are almost guaranteed to be incomplete, if

not distorting. But it’s pretty clear

what the pattern is of: it’s how you got to where you end up.

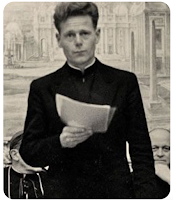

|

| Virgil Thomson (r) |

Sometime in the early 1990s, I had the television on, not entirely absorbed in what I think was a documentary film about

the American composer Virgil Thomson.

There was a brief scene, apparently filler, of Thomson at a party. He

was talking to a young man, who I imagine was troubled about his career or his

life. Thompson was looking at him

intently, and said very carefully and earnestly:

“The outcome of everything

is the way it happens, and the way it happens is the story of your life.”

It took me awhile to accept this but that’s the

pattern. That’s the retrospective

continuity: the story of your life. And as I am finding now, it begins to

become visible when the story is pretty much over, and you’re in the coda, or

maybe the last act.

In Buffalo it was still winter. I slept in Steve’s living room, for longer than I intended. Simon and Garfunkel’s Bridge Over Troubled

Water album had come out, and I learned the first song on the second side, “The

Only Living Boy in New York.” I played

it so much that a friend of Steve’s thought I’d written it. I also liked “Papa Hobo” from that

record. Together they represented my

moment.

|

| Bobbie and Bob Creeley |

The only reading I remember was from the bookshelf in that

living room: several books by William Carlos Williams, notably his essays

In

The American Grain.

I must have also been reading Robert Creeley’s newer poetry, since

he was teaching in Buffalo, and I was seeing a lot of him. I attended at least one of his classes,

spoke with him in his office, and was at an epic party in which, at one end of

the host apartment, Robert Creeley held court, surrounded by others, and at the

other end, his wife Bobbie Creeley was equally the center of attention. When Bob mentioned Bobbie's enthusiasm for palmistry and

I held up my liberally creased hand, he immediately sent me to Bobbie (later

known as writer and artist Bobbie Louise Hawkins), who, as predicted, exulted

in the challenge.

I was deliberately spending time at the English department

building, particularly one long row of offices, belonging to (among others)

poet John Logan, fictionist John Barth, and literary critic and gadfly Leslie

Fiedler, as well as Creeley. I learned

enough about them to find the ways they decorated the window in the door to

their offices appropriately expressive.

Logan’s window looked like stained glass, Fiedler’s was psychedelic,

Barth’s was blacked out, and Creeley’s was clear.

I met a lot of people in the department, as well as other of

Steve’s friends, especially at the almost weekly huge communal meals. Steve remembers that we both brought guitars

to a class he was teaching and improvised a song with lyrics by T.S.

Eliot.

But it was also a moment of crisis for SUNY Buffalo,

eventually including street demonstrations.

After awhile police of various kinds were called in, and there was

barricades and tear gas. Steve and I

mostly listened to the reports each evening on the campus radio station. But we also attended meetings, including a

big one of the faculty (that included graduate TAs) in the College of Arts and

Letters. The issues were wide-ranging,

including academic freedom (unjustified suspensions of faculty) and others I’ve

frankly forgotten.

|

| Leslie Fiedler |

Leslie Fiedler spoke about how serious it was to call for

the resignation of a university president—and why he was calling for it now. A

resolution of no confidence passed overwhelmingly (according to my notebook.)

Then a student came in shouting that police were on their way to a particular

campus building, and so all of us marched arm in arm to that building, where

nothing happened.

There was another moment I had reason to remember

later. Before the meeting started,

someone behind us cautioned that people chatting with each other needed to be

careful what they said because there were probably FBI undercover agents in the

crowd. What seemed a tad paranoid

though not crazy turned out to be broadly true, when the extent of FBI

infiltration of antiwar and related groups was revealed. Some agents were even provocateurs, pushing

radical groups to violence.

I’d never entertained participating in premeditated

political violence, and I was skeptical of its benefits versus its human and

moral costs. My attitudes towards “revolution” were also complicated. I was

selective in what I felt needed to change, and how to go about obtaining that

change. Some of these attitudes were

not quite conscious, so I learned something from a moment in Buffalo.

Richard Ellmann, author of the biography of James Joyce that

had meant so much to me, was teaching at the university (though I never met

him.) But I read somewhere that his

collection of Joyce memorabilia was on display that month at the university

library.

When I went to see it, I couldn’t find it. A library official asked if he could help

me, and when I told him, he said that unfortunately the display had to be put

back in storage because of the ongoing strife in the streets. He must have seen my expression of

dismay—I’d never dreamed that angry students would sack the library but at the same

time, it didn’t seem like an outrageous precaution. And I suppose that, with my long hair and jeans, I was a bit

ashamed to be a cause of such anxiety.

But he saw right away that I was a Joyce enthusiast, and

sympathized.

|

| SUNY Buffalo campus |

At some point in my Buffalo exile, I made a trip over the

Canadian border for a quick visit with Bill Thompson, my former housemate our

senior year at Knox. I met his friends

from the University of Hamilton where he was (or had been) a graduate student. So cold and insistent was the Buffalo winter that it actually was warmer in Canada.

It was at the University of Hamilton that I had my first

exposure to what was then called Women’s Liberation. I attended an open forum on the subject, run with authority by leaders of a campus Women’s

Liberation organization. It was an

eye-opener, or as we would soon learn to say, a consciousness-raiser. A lot of their points I experienced as valid

immediately, and others it took a short while to admit. I was troubled however by how the women leaders

treated a woman in the audience, who said she didn’t think women had to have a

career to feel liberated or be fulfilled—she felt liberated working in her

garden. They fell on her like a ton of

bricks. Today it seems like a first

iteration of the “woke” moment: it’s liberating side, and it’s tyrannical side.

I was still in Buffalo in April (where it was still winter),

for the very first Earth Day. Some 20

million Americans marched or otherwise participated. It was a big deal. (I

wrote more about this

here.) I heard

Ralph Nader speak, and engaged a garage mechanic in a conversation about how

ecology could generate jobs.

In general Buffalo had calmed down in late April, until

President Nixon announced the U.S. incursion into Cambodia, widening the

Vietnam war. The university, along with colleges across the country, immediately

erupted. On May 4th,

National Guard troops shot and killed four Kent State students. The war, it seemed, had come home. There were larger protests at even more

colleges, and a national student strike. For those of us a little older, Kent

State crystallized a feeling we’d had for years: that we were enemies in our

country.

The University of Buffalo was shut down, and Steve and I

spontaneously decided to head back to Knox College in Illinois, perhaps from

some homing instinct in this crisis time.

I had miraculously (and largely through the efforts of

Robert Creeley, I’m convinced) been accepted into the SUNY Buffalo graduate

English program for the following fall.

But I no longer saw myself staying there. Whatever I was going to do or

be next, it wasn’t going to be in academia after all. In the immediate sense I’d abused Steve’s hospitality for too

long. So I knew I wasn’t going back to

Buffalo.

I had also been accepted at the Cummington, Massachusetts

summer arts community, all expenses paid.

Before and after that, I was back to “nowhere to go.”

We got in Steve’s MG, and by the time we got to Ohio—and

drank coffee while being stared at by truckers—we realized that outside of

Buffalo, and despite the ongoing crisis, it was spring.

The story of that Galesburg visit—including my participation

in The Students Are Revolting and the takeover of an administrative office, as

well as the political books of the time—is told in a prior post indexed to this

series, published on the 50th anniversary of these events. Next in this sequence, I’ll pick up the

story at Cummington and Cambridge, Massachusetts in the summer of 1970.