“No Thyself”

sidewalk graffiti, Berkeley 1969

Many of the countercultural concerns I heard in Berkeley were the same I’d seen in Boulder that summer (and fall) of 1969: astrology was big, we often consulted the I Ching. “Hexagrams to horoscopes, these add the symbolic dimensions to our lives erased by technocracy,” I wrote in one of my Berkeley notebooks.

There was also a lot of emphasis on alternative medicine and health, organic food and so on, as well as the evolving countercultural economics and politics. But in Berkeley I quickly experienced the latest echoes of a West Coast approach to psychology.

I kept hearing about something called encounter groups, which may or may not have been related to the Gestalt Therapy that Fritz Perls had been practicing, mostly at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, down the coast from Berkeley. I don’t remember the exact vocabulary but there were certain phrases that I heard a lot, from the moment I got there.

Somewhere in the years since then, I picked up a vintage copy of Perls 1969 book, Gestalt Therapy Verbatim, which is basically a series of edited transcripts of Perls’ sessions, in which he focused on an individual (usually telling a dream, or trying to) but with a large group as audience and occasionally participants. Reading this recently, I began to see the likely source of a lot I heard in 1969: the idea of stripping away “your bullshit,” of confronting illusions and habits of evasion, and being honest with yourself and others...The idea of identifying a personal mythology, which is both a public face and a private identity, and which in both instances could be fake and self-delusion... The often repeated exhortation to “get out of your head” and pay attention to what your senses and your body were telling you.But if I was ever introduced to Gestalt as a system, it escaped me. I recall only fragments, most conspicuously the one that became a hippie cliche: doing your thing. It apparently came from what Perls called the Gestalt Prayer: “I do my thing and you do your thing. I am not in this world to live up to your expectations” (I heard that sentence a lot) “and you are not in this world to live up to mine. You are you, and I am I, and if by chance we find each other, it’s beautiful. If not, it can’t be helped.” (The last part of the prayer, a little harsh for the love generation, I’d never heard before.)

Other elements of Gestalt have become absorbed into various sorts of therapies, such as Perls’ method of interpreting dreams (his idea was that every character—in fact, every thing-- in the dream is you.) Perls had some concepts and models (he was clearly influenced by Zen Buddhism) but even if I’d been sophisticated enough to understand this system, I probably still would have found key concepts lacking, such as the ones I eventually found through Hillman and Jung. So I noticed this element of Berkeley counterculture without entirely understanding it.

But the interest in psychology would be a natural outgrowth of new living arrangements that characterized the counterculture, which involved individuals intimately in groups. (Through Jung we get the concept of introvert, which explains a lot of how I experienced these months, when people intensely relating was stimulating for awhile but quickly exhausting.)

Which might make this a good moment to mention what may be obvious: that I’m leaving out of this account most of the personal and interpersonal events and impressions that absorbed so much time, energy, attention and emotion at the time. I’m not minimizing them—and I do have memories—but I couldn’t do them justice in this space, or possibly at all. But of course, all of that interpersonal and intrapersonal activity was one basic reason for this interest in new psychologies, especially through the lens of insights gained from cannabis and psychedelics as well as the evolving counterculture itself.

As “science” is finally confirming, cannabis and psychedelics really do expand your mind, and though this may include a consciousness of connection (“It’s all one, man!”) it happens inside your own head. So the first effect is personal, and psychologies deriving from these experiences were starting to develop in these years (and Berkeley remains a place where they continue.)

Today the buzzwords of “positive psychology” include self-fulfillment, flourishing, achieving potential. These are influenced by what happened in the 1960s, since before then, the buzzwords were about fitting in, fulfilling your role, adjusting to society. These of course persisted, and became the basis for the sneering title given to the 1970s—the Me Decade. While excesses of self-indulgence and selfishness were part of that decade (though with a cynically different spin, these became major themes in the Reagan 80s) and some crazy stuff spun out from what had been the human potentials movement, the attention to physical, mental, and societal health, spiritual growth and an exploration of potentials were unjustly vilified and ridiculed.

But by the time I got to Berkeley, and communes and other new living forms were features of the counterculture, the concentration only on the inside of one’s head was turning out to not be enough. Relations to others—and therefore to one’s social self, which implied a different order of psychological understanding—became necessarily active concerns. Hence the encounter groups and Gestalt therapy.

Still, what we are likely to forget is that the drugs, the music (especially the music) and even the psychologies and spiritual trips were responding to a suppressed need for joy, for experiences of ecstasy. So much of the cultural forms were meant to create an absence of hassles—“hassled” was a big word, a big problem—which was a precondition for freedom. And freedom in turn was a precondition to joy and ecstasy. And this was part of the social arrangements as well—people who could share ecstasy. These were persistently felt needs of the time, along with an insistence that it was all possible. Today it mostly may seem inconceivable. Yet the desire for ecstasy is perennial.

Psychedelics entered my Berkeley experience only once I can recall. In a hapless attempt to earn some “bread,” members of our household acquired and attempted to deal a small quantity of what was purported to be LSD. But most of what wasn’t given away was stolen. We saved enough for one trip apiece. I had mine in the living room with the Beatles Abbey Road album.

Others in the house (I learned later) had a heavier trip, getting deep into psychological complexities and relationships. So while my experience was more pleasant—maybe even a little ecstatic-- it was also solitary, and beyond the music, not memorable. (But Abbey Road is the music I associate with my Berkeley time, and another album in the house I listened to a lot, Judy Collins Who Knows Where The Time Goes.)

Of course, cannabis (as we call it now; grass was a more preferred term then) was more ubiquitous. I remember walking down a street in Berkeley with someone else, entirely engaged in a conversation, and about to pass two young men walking up the hill, also conversing. One of them was holding a Berkeley joint, wrapped in yellow paper. As we passed he simply handed me the joint and we all kept going.

Combining the psychology of the counterculture with its spiritual quests was Stephen Gaskin’s Monday Night Class.

Any number of us in the household climbed into David’s bus on several Mondays to ride over to the Richmond district of San Francisco. There on the Great Highway edging the ocean was the former Ocean Beach Pavilion Ballroom, re-named the Family Dog, which was beginning to host now legendary rock concerts that very summer of 1969, promoted by the manager of Janis Joplin’s band, Big Brother and the Holding Company. But on Monday night, this huge space belonged to a single slim bespeckled man, a former Marine and creative writing teacher called Stephen Gaskin.Upwards of a thousand heads crowded their bodies into available spaces on the floor, as Gaskin held forth on a raised stage. He was riffing on a vast area of what would be classified as Western and Eastern metaphysics, esoteric philosophies, religion, psychology, what we’d now call neuroscience, physics, biophysics, the history of the species, as well as areas then called the occult, mystical, paranormal, and so on. This started as an actual class at San Francisco State called Unified Field Theory, and grew from there. The entry point to it all was the psychedelic experience, the stoned consciousness; the insights not from on high, but from being high. Many of his riffs became a book titled Monday Night Class, and it is still in print in a revised and annotated edition.

From my notebooks it’s clear that we in our household talked about things he said, and I extrapolated and commented in my notes, though the actual content is less clear. The ideas were stimulating. Energy is focus. Truth is experienced. Consciousness is paying attention. Pay attention!Considering that most of his audience was high, there was a good chance that those who were paying attention to him were really paying attention. Words on a page can’t convey the weight of those words spoken in that moment.

“Get high, stay high,” he said. When you are high you know the truth, and no one can lie to you. These statements, seemingly about drug highs, may have been metaphors for higher consciousness and a particular energy state, but was that how they were heard?

So I was also wary, suspicious of his certainty. He never qualified his statements—everything was just that: a statement. My Catholic immersion made me sensitive to the sound of dogma, and to any sort of guru attitude or energy. But his sort of rolling synthesis was what a lot of people in the counterculture talked and thought about. If they weren’t as erudite as Stephen, they also came at it from their own experiences, expertise and education.

For the psychedelic or stoned experience was not only sensation, but perhaps the flying open of doors to a new consciousness, including cosmic consciousness (It’s all one!) These feelings and insights suggested connections to indigenous and ancient approaches, ignored and even forbidden in the modern western world, even in the 60s.

While Stephen spoke in metaphors of electricity and quantum physics as well as auras, such stoned insights and ideas found resonance in non-modern and non-western traditions. So it was the 60s that jumpstarted the already seeded Bay Area interest in Buddhism and other Eastern systems. Now pretty much part of the mainstream, they were foreign then. (Fritz Perls interpreted the Buddhist “nothingness” as meaning process, a Gestalt insight that might be revisited in terms of the now more familiar meditation practices.)

So it seemed a natural outgrowth of the Monday Night Class when Stephen announced an upcoming three- evening event he dubbed the First Annual San Francisco Holy Man Jam. Guest “holy men” included Ram Das, Timothy Leary and Alan Watts. We attended one evening, when Alan Watts spoke. Watts had been the charismatic voice for Eastern insights for decades in the Bay Area. His radio talks are still replayed. I seem to recall that Mike Hamrin praised in particular Watts’ The Book On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are, a modern interpretation of insights from the Vedanta philosophy of Hinduism. (Who you really are might be described as a persona of the eternal.)What I recall about this evening is the festive atmosphere, and the giddy experience of being ordained a minister in the Universal Life Church, sanctified by a pious inhalation on the longest bong I’d ever seen, maybe six feet.

|

| Joni Mitchell and Joan Baez |

As far as that goes, I missed Woodstock itself that August, and only read about in Life Magazine in a bookstore on Telegraph Ave at least a week afterwards, shocked that it took place in the old East while I was finally on the happening West Coast.

Zen Buddhism was a more fashionable element of the counterculture in the Bay Area than elsewhere, but I missed the substantial change in emphasis, from concepts to practice, that was underway, principally emanating from the San Francisco Zen Center. (Speaking of practice, however, I did attend a free, open acting class at San Francisco’s ACT, given by Del Close. Now revered as a master of improvisational comedy, he was with the San Francisco improv group The Committee, between gigs running Chicago’s Second City. Simply sitting in a large auditorium, I learned more about acting in that hour than in college or anywhere afterwards, although it took me awhile to realize this.)

Instead I immersed myself in my Berkeley neighborhoods. Berkeley extends from the residential hills steeply and then gradually down to the flat downtown area, with the UC campus and the Telegraph Ave artery cutting across between them. The hills were known to us as the land of the rich, and we only went up there a few times in the bus to scout out the furniture, appliances and other ritzy stuff left out on the street for garbage collection. The downtown was mostly the residual province of the middle class straights.

Since our Shattuck Street digs were close to downtown, I did visit a few places there, mostly an Italian restaurant called Giovanni’s, though mostly for coffee and maybe a small salad. I first went there because I’d met someone in Colorado who had waitressed there. I mentioned her to a cashier, who remembered her, and that got us acquainted. So I also went there for the company.

But I spent most of my wandering time along Telegraph and on the UC campus. Between hippiedom and academia—yes, that was me.

The places where these worlds—and many others—came together were the bookstores, and at that moment, Telegraph Ave had a lot of them. I’d never experienced that before: going from one bookstore to another to another, in a day or over days, available to me every day. I was in a daze. At times I felt overwhelmed and anxious—so many books, so little time! And no money to buy them anyway! I worried that I didn’t belong there, that they would find me out and ask me to leave. Sometimes I was calm enough to accept that I was in Wonderland. And eventually it began to be a little normal to be there.

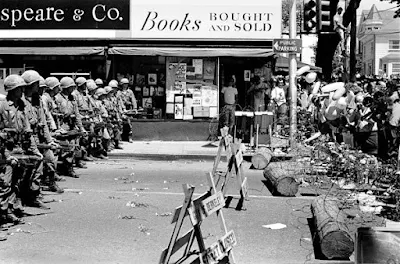

Apart from a number of small and specialty bookshops on Telegraph and adjacent side streets, there were at least four very big bookstores on the first few blocks of Telegraph from the Berkeley campus. There was the university bookstore itself, then Cody’s Books, and two big used bookstores: Moe’s and Shakespeare and Company. I don’t remember how big the Shamhala bookstore was inside, but it had a conspicuous storefront window.Cody’s Books was the most prominent in many ways, and the one that remains in my memory. But though I found photos online that showed several of these stores, I haven’t come across one of Cody’s as it was in 1969. The closest are photos of both exterior and interior in 1974 or so, which look glitzier than I remember. What I seem to recall is the huge glass doors that retracted so that the bookstore was open to the air and the street. When I walked by I could literally see into the bookstore, and that proved irresistible just about every time.

Cody’s sold new books, lots of paperbacks (its initial claim to fame) but also lots of literary titles in hardback and periodicals. One of my last experiences in Cody’s was picking up the new issue of the Carleton Miscellany, with my review of Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five. I also got my check for it—my first paid piece of writing—while I was in Berkeley.

Cody’s became part of Berkeley culture and politics as well. During 60s demonstrations that often included clashes with police (always referred to in 1969 Berkeley as “pigs”), it became a medical aid station for wounded antiwarriors.

Judging from notebooks, I not only browsed but read in the bookstores, but I must have purchased a few used paperbacks somewhere. For my other activity on Telegraph Av was coffee and reading (and writing—I’m surprised to find two pretty good poems in my notebook, and parts of a third.) And occasionally, eating. Our meals on Shattuck were almost exclusively oatmeal in the morning and brown rice with whatever vegetables came to hand in the evening. (These might come from dumpster dives behind the Co-op supermarket, where old but still edible veggies were carefully placed by staff.) I supplemented this diet with tuna salad sandwiches at a university cafeteria, though they would be more accurately described as a thin smear of tuna paste on sliced bread, with some carrot sticks on the side. But it was cheap.

I also frequented a small Mexican restaurant on Telegraph called La Fiesta. They placed a basket of chips on the table and gave you a glass of water, no matter what you ordered. What I usually ordered was coffee. But I got the chips, and sympathetic waitresses might refill both cup and basket as I sat absorbed in my reading. The taste of those chips and that coffee still adhere to at least the first two volumes of Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandrine Quartet. (On my last visit to Berkeley's Telegraph Ave in 2003, that restaurant was still there, pretty much the same—though it was just about the only thing that was.)In Justine, Durrell’s prose was mesmerizing even when I’d lost track of what was going on or why. I then found a volume of Durrell’s correspondence with Henry Miller, probably in Cody’s, and read some of it there.

I quote in a Berkeley notebook from Kenneth Patchen’s Journal

of Albion Moonlight, an apocalyptic antiwar novel that was all but

suppressed in 1941 for the next 20 years but became a legendary work of the San

Francisco Renaissance and Beat era of the 50s and 60s. Patchen was revered as well within the

counterculture (Jim Morrison was a fan.)

I have a used copy now, but I don’t know when I acquired it. Maybe in Berkeley.

My notebooks also mention Frank Budgen’s book on James

Joyce and the Making of Ulysses.

Budgen was an artist who knew Joyce in Zurich. I recognize the paperback cover of the time, so I must have read

that one and possibly owned it, though it is not now among my Joyce collection.

My notebooks also mention Frank Budgen’s book on James

Joyce and the Making of Ulysses.

Budgen was an artist who knew Joyce in Zurich. I recognize the paperback cover of the time, so I must have read

that one and possibly owned it, though it is not now among my Joyce collection.

However, my continuing Joyce obsession did lead to a compulsive purchase. High on a shelf in Cody’s Books I spotted the second two volumes of Joyce’s letters, edited by Richard Ellmann. Though the price for these hardbacks was a bargain, they were still too much for me.

They were high enough on the shelf to require a ladder, so I felt diffident about asking to look at them more than once. But every time I went in or even passed by, I glanced up to see if they were still there. Finally, when I knew I was leaving Berkeley, I broke down and used some of my travel money to buy them. I still have them, though I can’t say I’ve spent a lot of time reading the letters.

Those bookstores had a quantity and variety of books, including arcane collections of the past—from obscure literary and specialized scholarly works to an era’s worth of pulp science fiction—that would have fed a lifetime of voracious curiosity. But they didn’t last for my lifetime.Cody’s was still there in 2003, both on Telegraph and downtown Berkeley, where I happened on a reading by Maxine Hong Kingston, shortly after my review of her Fifth Book of Peace appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle Book Review. (I met her afterwards and she was pleased that my review “got it.”) But the Telegraph Ave. Cody’s closed for good just three years later in 2006—it had been at that location since 1965-- and the downtown store closed two years after that, victims of high rents.

Shakespeare & Company closed in 2015, after 51 years. The Shambhala bookstore opened in 1968, offering spiritual books with an emphasis on Buddhism. In 1969, Shambhala published its first book, and has since become the foremost publisher of non-Western books on spirituality in America. The publishing side soon moved to Boulder and Boston, while the Berkeley bookstore lasted until 2003.

Many other smaller bookstores of that era are also gone. Of the big four, only Moe’s remains, and the university bookstore, which if it follows the national pattern, would be mostly sweatshirts and other branded merchandise, with barely a whiff of a non-textbook, or even a book shelf.

|

| Gary Snyder (l), Lew Welch (r) with fellow poet and Reed College pal Philip Whalen (c) |

Near the end of my stay in Berkeley, I attended a poetry reading for Ecology Action and the Ecology Center that turned out to be a bit historic. It featured some of the better known poets of the time in the Bay Area, a group that likely never read together again. I wrote about it at the time.

The event was held in the Pauley Ballroom on the UC Berkeley campus. I arrived early enough to get a seat in the orderly rows of folding chairs. Eventually the master of ceremonies, one of the ecologists, came to the microphone. “I know this might be difficult, but if somehow some room can be made at the back of the ballroom, more people could get in.”

Instantly a cacophony of scraping chairs as everyone moved them towards the front, obliterating the rows and clumping closer together. The ecologist m.c. watched, and when it was quiet again he said, “What just happened was very much like the action of wind, or water. I think we’re ready to begin.”

The poets who read included veterans of the Beat era: Gary Snyder, Michael McClure, Lew Welch and David Meltzer. Welch and Snyder were former classmates and roommates at Reed College, and maintained a close friendship. The more recent counterculture star was Richard Brautigan.

Gary Snyder was the crowd favorite (I noted). During some poems there was applause after every line. Brautigan read his short non-sequiter poems, marching or preening around the stage during the laughter and applause between them. McClure was more quietly but respectfully received. David Meltzer spoke of the sensations of a city boy moving to a cabin in Marin County.

I’d heard Snyder read at Knox College some three years before, which seemed like a lifetime, and maybe in a way it was. But I recall—and I wrote at the time—that I was otherwise most impressed by Lew Welch.

Besides being a paean to the Bay Area, where (he said) all American revolutionary movements began, Welch’s poem sums up the movement of Europeans across North America, pushing beyond one frontier after another. Essentially it’s the story of humanity, always looking for a better place, and despoiling it before they move on, knowing there’s more. But in California, they reached the limit. Welch’s haunting refrain was: “This is the last place. There is nowhere else to go.”

In the context of an ecology reading, he was talking about Earth itself. I never forgot that line, or that moment.

Less than two years later, Welch disappeared into the Sierras with a gun, leaving behind an old suicide note. He was never found. At a publication event for a posthumous volume of Welch’s poems in 2012, Snyder said Welch could not overcome his alcoholism. David Meltzer called Welch his “demented mentor.” When I spoke on the phone to Michael McClure in 2004, I mentioned this Berkeley reading and he remembered it as a special occasion.

Finally, there was a repeated experience of my Berkeley stay that for me characterizes that time and place, or at least the brighter side of it. It was the Saturday Night Midnight Movies.

First, though, you have to know something about the tradition of the Saturday afternoon matinees at the movies. Back when most films were seen in the movie palaces of cities and towns, there were Saturday matinees for children, beginning in the 1930s and continuing probably until the hegemony of mall cinemas and multiplexes.The standard movie program for adults as late as the 1950s and possibly later called for: a cartoon, the newsreel, a short (usually a comedy, like Chaplin or Laurel & Hardy), the latest episode of a serial (always ending with a cliffhanger), previews of “Coming Attractions,” a “B” movie feature, and then the main feature, just released that week. The Saturday matinee started out with the same basic mix, but the features were selected for kids. The main feature was often new or fairly new, but might be an old favorite.

By the time my early Baby Boom generation was old enough in the 1950s, the Saturday matinee was even more elaborate. It might start at noon or even before, with a dozen or two or three dozen cartoons. At least one of the movies might be an older science fiction, horror or adventure film. The entire program might keep us in the theater until 5 p.m. The point being that everyone in Berkeley in 1969 could have attended Saturday matinees as children.

I don’t remember which theater held the Midnight Movies. I have a vague feeling it wasn’t the Repertory on Telegraph, where during my stay I saw Yellow Submarine and Lindsay Anderson’s ...If again, but downtown. In any case, the Midnight Movies in Berkeley were essentially a Saturday matinee program for heads. There was no disguising the assumption that everyone in the audience would be high, or would be getting high during the shows. Being high in some ways returns the sensory acuity, intense belief and openness that the years erode. So this was the Saturday matinee on dope, and we were children again.

There were differences. The audience behaved badly (in a fun, good-natured way), which no theater manager would have tolerated for long on Saturday afternoons. (I can remember only a few instances of general rowdy behavior in my youth, mostly when the movie was boring. I especially recall a showing of one of the Lone Ranger feature films (there were two, with basically the same plot.) As we walked in, we were all given a plastic silver bullet as a movie promotion. But the movie wasn’t very engaging, and I remember being in the balcony at one point, watching the silver bullets crisscrossing in front of the screen as kids below threw them across the auditorium.)

At the Berkeley shows, bad behavior usually amounted to throwing popcorn at each other, crawling over seats and being loud in response to what was on the screen. It was hilarious. But as it was Berkeley there was also political critique. Whenever a policeman appeared on the screen, there were boos and shouts of “pig!” When the Laurel & Hardy or other comedy short was silent, the entire crowd read the subtitles out loud together, and if the line was addressed to a police officer, usually some version of a Keystone Kop, the word “pig” was spontaneously added. Crowds in Berkeley, I wrote at the time, weren’t like those in other places: people there seemed comfortable in the identity of a crowd. That was certainly true at the movies.

There was a newsreel, but it was from some week in the 50s or 40s. There were cartoons, a serial, a short, and a feature. Some were culled from the archives of our childhood: I specifically remember seeing George Pal’s 1951 apocalyptic science fiction movie, When Worlds Collide. It was the first time I’d seen it since one of those childhood matinees, so I was revisiting it in that late 60s apocalyptic context. But after the world literally ends and a single space ship of survivors lands on a new world that I had experienced as wondrous, I saw this time that this new Eden was an obvious painted flat backdrop. Which was another kind of a message. The other movie I recall from a midnight show was the Busby (no relation to the city) Berkeley musical Gold Diggers of 1935. It was the first B.B. movie I’d ever seen, and it was on the big screen, augmented for me by being high, so I was mesmerized. But the wide-openness of that state has had its drawbacks in my life, and this was one of those memorable times.I was totally immersed in the long and immensely elaborate song and dance sequence for “Lullaby of Broadway,” and totally unprepared—and undefended—for the climax, in which at the height of the frenzy the female singer is suddenly pushed accidentally off a balcony and falls to her death. So much for musical comedy. This may or may not have been a dream sequence, but I was shocked and sobered. A downer, man. And as some things do in that state, it seemed portentous and symbolic beyond the bounds of an old movie.

All during my months in Berkeley, I was writing and receiving letters. Apart from friends and family members, a lot of them were to and from Joni, who had started teaching in Connecticut. In a way also I was being called home. Eventually I decided to head back East.

Of my original housemates on Shattuck, Phil had already left. The others were embroiled but restless. Mike Hamrin’s girlfriend referred to my “solemn and tacit presence,” a characterization I’ve never forgotten, for it was both a revelation and inarguable.

At times it was a close thing, but my life didn’t catch in Berkeley. My head was not always there, and not always in the present. Maybe I was too much the spectator. “All Berkeley really needs,” I wrote in a notebook, “is a proscenium arch.” Though with the gate to the UC campus, maybe it had one. And it was on the UC campus one sunny afternoon that a stray dog came straight over to me, licked my hand, lay down at my feet, and went to sleep.