Television and I grew up together. This is our story. Fifth in a series.

I was stuck inside one weekend afternoon in December 1952, probably a Saturday. I was six years old, and had just started first grade at Sacred Heart School in September. One of my aunts on my father’s side was visiting, accompanied by at least one daughter. All of my Kowinski cousins at that point were girls, so they would play with my sister. That usually involved a lot of screaming and running around. On this day they would erupt from my sister’s room and barge into mine, point at me, scream and run away.

My mother and my aunt, busy talking over coffee in the kitchen, were no help. So I parked myself in front of the television set in the living room, and turned it on, with no expectation of what I might see.

What I saw was a man in a futuristic Flash Gordon outfit, explaining to others dressed in a similar way that their planet was about to explode. They got angry and didn’t believe him.I had stumbled upon the first episode of The Adventures of Superman. But I’d missed the opening—the “Look! Up in the sky!” and the “faster than a speeding bullet” and probably the most famous description in early television, of the “strange visitor from another planet, who came to Earth with powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men.” I even missed the name: Superman.

I started with that first scene on Krypton. So I didn’t really know what I was watching, but I was mesmerized. I don’t know how much of the story I followed that first time, but by the end I’d seen Clark Kent become Superman, and fly to the rescue—of a man dangling from a dirigible.

I know I felt completely absorbed in that world, and when the program ended I felt bereft, confused. I didn’t know what to do. My mother and my aunt were still in the kitchen. I didn’t have anyone to talk to about it. So I went back into my room, closed the door, and thought about it. And then I did what many others would eventually do: I tied a blanket around my neck to create a cape.I watched episodes all that school year. At the same time I was getting my first doses of Catholic doctrine, mostly through stories Sister Mary Kathleen would tell every morning (although since first and second grade were taught in the same classroom, I probably also got my introduction to the Baltimore Catechism.) For awhile I started to think of Superman’s father Jor-El as God the Father (anticipating a theme of the Christopher Reeves’ Superman movies.)

I was especially taken with Superman’s secret identity as Clark Kent, and the episodes in which that secret was endangered. Perhaps this had something to do with going to school, where I was no longer the hero of epics my playmates and I invented as we performed them, but I had to be meek Clark Kent and fold my hands and put them in the center of my desk.

Still, I didn’t want to keep my true identity a secret from a blond second grade girl named Judy, and once stood outside the classroom where I knew she was, significantly glancing to the sky and making those quick movements George Reeves did, as I ran off to transform into the Boy of Steel. Somehow I believed she would interpret my actions correctly—the first of many such mistakes.But before that December day, I was a complete Superman innocent. Superman did not exist for me until I saw that first television episode.

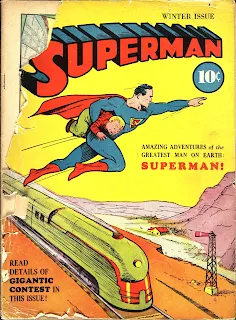

But Superman had been around since his first comic book appearance in 1938. He was an immediate hit, far beyond comic book readers. His first “personal appearance” was on Superman Day at the 1939-40 New York World’s Fair. Superman has still sold more comic books than any subsequent superhero.

A radio show soon followed in 1940 (the voice of Superman belonged to Bud Collyer, who I would see as the mild-mannered host of the TV game show “Beat the Clock”), which ran until 1950.

Then a series of theatrical cartoons in 1941 and 1942, the first nine of which were made by the Fleischer Studios, with an unusually large budget. (Eight more were made by different directors, with lower budgets and a choice of wartime stories that exposed elements of the racism of the time.)After that there were a couple of live action movie serials in 1948 and 1950, with Kirk Alyn. These were the most profitable serials in movie history, outdoing the classic Buster Crabbe Flash Gordons. In these, Superman was seen flying in animation.

The next step was a feature film in 1951, though it was really a low-budget test drive for the upcoming television series. Superman and the Mole Men starred George Reeves as Superman and Phyllis Coates as Lois Lane, and clocked in at under an hour. It would later be edited into two half hours for the TV series. This time, and for the first time, a live action Superman flew.

The first season of the television series The Adventures of Superman went into production immediately after the movie was shot in the summer of 1951, with the addition of Jack Larson as Jimmy Olsen, Robert Shayne as Police Inspector Henderson and John Hamilton as Perry White, editor of the Daily Planet. Nothing happened for awhile until Kellogg’s cereals (eventual sponsors of the radio version) agreed to sponsor it. It was a syndicated program, which means it wasn’t on any network schedule. So it was up to individual stations to take the chance.The first to air it was WENR in Chicago, in September 1952. Then Davenport, Iowa and other small Midwestern markets in October. Then Buffalo in November, and Pittsburgh’s WDTV in December. Most scheduled it in an open early evening slot. I may have seen a Saturday afternoon re-showing from the previous week, a not uncommon practice at the time. Or it may have been where it was first scheduled, though it soon had an evening time.

Those of us in Chicago or in range of the Pittsburgh station got a head start, since the big markets—Los Angeles, Baltimore/Washington and New York City—didn’t air the first episode until the spring of 1953. Once it hit New York in April, though, the show was an instant smash hit.

|

| Kirk Alyn and Noelle Neill in the movie serial |

The Adventures of Superman made six seasons of half-hour shows, though only the first two were of the full 26 episodes (which were then re-run for a year of 52 weeks.) The next four seasons had 13 new episodes each, with the second half of the season as re-airing of previous episodes, including from earlier years. Starting with the third season in 1955, the series was shot in color, though most stations didn’t air it in color until there were enough color sets, at least a decade later.

The color episodes helped extend the life of the series, but it didn’t really need much help. The Adventures of Superman was seen off and on for decades—so kids in the 60s, 70s, 80s and beyond might replicate something like my first-time experience. (One fan site I ran across was run by someone who first saw it on a cable station in 1986.)Superman was a touchstone during my entire childhood. Even in the 50s, Superman episodes were aired and re-aired many times, so my memories include responses from throughout my childhood. Still, when I’ve gone back to view these episodes on DVD, it’s been clear that my sharpest memories are from the first and second seasons.

I remember a moment in an early first season episode, “Mystery of the Broken Statues” (a variation on a Conan Doyle Sherlock Holmes plot) when Lois Lane suddenly cries in surprise, “Eureka!” I’d never heard the word before and wondered what it meant. I was fascinated to learn in one second season episode that diamonds are made from “coal, carbon: you put a lump of coal under a million tons of pressure for a thousand years, you get a diamond.” But of course, Superman did it with one hand.

And I recall Clark Kent playing with words when he teased Lois, “You wonder? No wonder that you wonder—you’re a pretty wonder-ful girl.”

Most of all I remember the attempt to kill Superman in the final first season episode, “Crime Wave.” Superman was lured into a large room, with geometrically shaped objects on the walls, presumably parts of the deadly device. The door crashes closed behind him—he tries to find a way out, pressing the walls at the corners, but he’s trapped. Then the “professor” in the next room turns on his machine, which attacks Superman from all directions with jagged lightning-like spears, crackling like electricity. Superman ends up in the center of the room, trying to ward off the rays with his hands, but sinking to his knees and then falling, inert on the floor.The professor comes in and pronounces him dead. The Big Boss (the one that Superman and the Metropolis police have searched for in vain) arrives to gloat—until Superman jumps up, and demonstrates how easy it is for him to escape. He has baited the Big Boss into revealing himself (he turns out to be the head of the citizen crime commission.)

This attack on Superman remained vivid in my memory for a long time. In fact, either it has been edited down since or I added every more agony in my imagination, because it seemed longer and more convincing. I “remember” specific moves that aren’t in there anymore.

But the stories in a sense were secondary: everything was in that still haunting opening—that strange visitor from another planet with powers and abilities far beyond those of mortal men, standing against a background of the stars, just above the Earth —energized my imagination and yearning.

I became such a loyal fan that I sent away for my “Supermen of America” membership and secret code book, probably from the comic books. (There were actually nine codes: one for each planet, including Krypton, but not, of course, Earth. I kept the booklet under my mattress.)The edge and seriousness of the first season became lighter at times in the second (in one episode, the bad guys are defeated by customers at a diner throwing pies at them) and in later years, plots began veering off into low-budget fantasy. (Though they could hardly compete with the comic book fantasies of that decade.)

Towards the end there were surreal moments that seemed to be coming from writers entertaining themselves, as when one hoodlum described what he was going to do with his share of the loot—he would build a big house that looked just like the penitentiary, so his friends would feel at home.

Still, there was a theme communicated to us, maybe even better when the early crime-fighting faded: Superman rescued those in trouble (even if too often it was Lois and/or Jimmy). He was the strong champion of those who needed help.This was the apparent paradox of Superman: a man so powerful he could take anything he wanted, but he only helped others. In a first season episode, a criminal mastermind type who is trying to figure out which Daily Planet reporter might be Superman in disguise, questions Lois Lane and speculates it might be her. Superman might be a woman, he suggests, because he defends the weak, and acts out of compassion. Implicit in this telling observation is that Superman redefine the conventional view of the masculine to emphasize altruism.

According to Superman’s chief creator, a young man in Cleveland named Jerry Siegel, this idea of the altruistic champion was a motive for the character’s origin in 1934. He described his state of mind at the time: “Being unemployed and worried during the Depression and knowing hopelessness and fear. Hearing and reading of the oppression and slaughter of helpless, oppressed Jews in Nazi Germany…seeing movies depicting the horrors of privation suffered by the downtrodden…How could I help them when I could barely help myself? Superman was the answer.”

Siegel and his drawing partner and friend, Joe Shuster, looked to science fiction, movies, pulp and comic strip adventures to shape the character and his environment. “Metropolis” came from the classic Fritz Lang futuristic movie of the same name. Superman’s dual identity was preceded by such fictional figures as Zorro and the Scarlet Pimpernel. Clark Kent’s look was partly inspired by silent film comic Harold Lloyd. Lois Lane was derived from a B-movie heroine, a reporter called Torchy Blane. (Shuster hired a Cleveland girl to model for his first drawings of Lois, and later married the model.)While the Superman costume was influenced by a variety of fictional characters, ultimately it comes from the shared imagery of the circus, for many years a major source of entertainment in America: the aerialist’s tights, the bodysuit with the underwear on the outside of the circus strongman, and the magician’s cape.

(The first comic strip character by a couple of years to wear what is now the standard superhero costume was The Phantom, who technically wasn’t a superhero because he had no superpowers. The Phantom was a long-running comic strip series, with one movie serial. I followed his exploits in our daily paper when I was old enough. A proximate inspiration for his costume was Douglas Fairbanks’ Robin Hood. Fairbanks was also a model for Siegel and Shuster’s Superman.)

When Siegel got to actually write Superman stories for comic books, the character he created was that idea of Superman that inspired him in 1934. In his first story Superman prevented a woman from being wrongfully executed. In his second, he went after a wife-beater.

In his 1930s adventures, Superman rescued miners in a cave-in, battled stock market manipulators and munitions manufacturers fomenting wars to sell their wares. He fought crime, but also poverty and unsafe labor conditions. He battled crooked politicians and lobbyists, slumlords, corrupt industrialists and crooked labor leaders alike. He came to the aid of individuals in trouble, and was devoted to the common good. He was a compassionate, high-spirited and humorous hero of the people, a wise-cracking crusader, like Spiderman with an edge.When others took over the comic books (Siegel and Shuster had signed away their rights to the character), the themes of righteous rescue and battling injustice were weakened, but never completely faded.

They emerged again from time to time in the 1940s radio show. On the very first radio broadcast Superman was described as "champion of the oppressed...who has sworn to devote his existence on Earth to helping those in need." Later on radio he would be described as “ champion of equal rights, valiant, courageous fighter against the forces of hate and prejudice.”

In 1946, a 16-episode series had Superman battling an organization based on the KKK ("The Clan of the Fiery Cross.") Reputedly based on descriptions by a reporter who infiltrated the Klan, for the first time it exposed its secret rituals as well as its crimes. The series was credited with reducing KKK recruiting. Notably it related this domestic racism to Nazi racism.The 1950s television series hit some of the same notes. The first episode of the second season echoes that first comic book story when Superman saves an unjustly convicted man from execution, just in the nick of time. In the pilot film, “Superman and the Mole Men,” Superman defends harmless and helpless aliens against a mob. He reasons with these men but then explodes: “Stop acting like Nazi storm troopers!”

(This Superman in the pilot movie had the harder edge of the early comic’s character. He saves the life of one of the mob, but when the man tries to thank him, all Superman says is, “You don’t deserve it.”)If Superman’s rescues became less pointed and more generically humanitarian, they still maintained that initial image to some degree.

According to author Thomas Andrae, Superman was “neither alienated from society nor a misanthropic power-obsessed nemesis but a truly messianic figure...the embodiment of society’s noblest ideals, a ‘man of tomorrow’ who foreshadows mankind’s highest potentialities and profoundest aspirations but whose tremendous power, remarkably, poses no danger to its freedom and safety.”

The Adventures of Superman series we saw in the 1950s was in large part a legacy of earlier versions. Besides the comic books, the early 40s animated cartoons made the key change of giving Superman the ability to fly, instead of just leaping tall buildings in a single bound. (They animated this in one sequence and thought it looked dumb, so they got permission from the comic book company to show Superman flying.)The animated series in particular began the evolution of the similar theme music that continued until John Williams made it definitive in the first big budget feature film in 1978. But the 1950s TV version was also exciting. We would dat da da, da da da da the melody out loud while we played.

The radio show also added Kryptonite, the Daily Planet as the newspaper’s name, and the characters Jimmy Olsen and Perry White. The comics then absorbed all of it. Though he was invented for radio, it was the TV version of Inspector Henderson that persuaded the comic books to include him, too.

|

| Jimmy Olsen (Jack Larson) and Lois Lane (Noel Neill) |

But by the second season the TV series settled into itself. Noelle Neil as Lois Lane was a key to the difference. She was a good-natured skeptic in relation to Clark Kent, but without the withering contempt, and treated Jimmy Olsen as more of an equal. That worked better with the new interpretation of Clark Kent, and helped elevate the increasingly popular Jimmy Olsen.

There was a relationship, a camaraderie among the principals that transcended some of the hokey stories, without ever seeming insincere. This happy family was more reassuring to kids. The suspense in the stories was sometimes furnished by threats to Superman (especially Kryptonite), but more often the suspense was whether he would find out where the trouble was and get there in time. Of course, all this was the surrounding sideshow for what we sat down to see: Superman flying, bursting through walls, facing bad guys with their bullets bouncing off his chest. As children we may not have noticed, but there’s no hiding what a low-budget series this was. It was shot very quickly, with scenes in the same location but for various episodes shot on the same day—one reason that the characters wore pretty much the same clothes all the time. When the series was shot in color, those clothes got even more similar: they were all mostly in shades of blue, presumably because they would also register well in black and white until the color sets came along.And those outfits in the origin episode that look like the ones in Flash Gordon? One reportedly was worn in a Flash Gordon serial, while others had appeared in other serials such as Captain Marvel and Captain America.

The absurdities became in part a kind of television convention, such as the opening shot of the huge Daily Planet Building, in which it seemed that about five people worked. They got out a metropolitan daily newspaper with an editor and two and a half reporters.

The same special effects shots—especially of Superman flying—were shown over and over. Other shots—Clark Kent running down the alley to become Superman, or Superman landing in front of a wall of boulders—were also repeated often, even when not entirely appropriate. But to us I suppose it was all ritualized. Perhaps that early childhood insistence on repetition (the same story over and over) never completely goes away (playing the same song over and over.)

The low-budget nature of the TV show unfortunately extended to the shockingly little the cast was paid. Eventually George Reeves was paid decently, but the others all had to live modestly and insecurely. John Hamilton (Perry White) lived in a bungalow and took a city bus to work on the Superman set. They were all cut out of the residuals paid over the many years that these episodes were repeated. (But then it took Siegel and Shuster several lawsuits to begin to get a tiny piece of the huge action from their creation.)It took more than 20 years after the TV show but the character of Superman went on the big screen in a very big way in 1978, with the first of the four Christopher Reeve Superman films. To me Reeve is the definitive Superman, as well as the definitive Clark Kent.

More television shows followed, and more and even bigger movies. Superman was the first superhero, and now superheroes are a genre in themselves. They dominate feature filmmaking and exhibition, and with films that cost more than the annual budgets of some countries, not to mention the combined annual incomes of millions of people. Superhero films get bigger and bigger, as teams of superheroes battle teams of super-villains on a cosmic scale, with the survival of worlds, the universe and everything at stake.

Now the human scale of the TV Adventures of Superman is almost completely lost. The idea that superheroes might waste their time rescuing miners after a cave-in, fighting a slumlord or a protection racket targeting small storekeepers, saving a child from harm, or even dealing with the unfortunate consequences of goodhearted but misguided inventors, would seem beneath them, not to mention failing to generate big enough visual effects battles, explosions and loud mayhem.For all its flaws, the 1950s TV show better represents the rationale and the uniqueness of the Superman character, including human wish fulfillment to address human scale tragedies, in which the worst of it includes feeling powerless. Something a six year old understands very well. Yet the message was part of the character: if you have power, you use it for others, and for the common good.