“Literature, as I saw it then, was a vast open range, my equivalent of the cowboy’s dream. I felt free as any nomad to roam where I pleased, amid the wild growth of books.”

Larry McMurtry

Adam Gopnik loves reading cookbooks, collections of letters, and James Bond novels—pleasures, but not guilty ones. “If you can tolerate one piece of advice,” he says, “it’s don’t segregate the great continuum of reading. “”To be a good reader, paradoxically, doesn’t mean being a discriminating reader, it means being an omnivorous reader,” he explains. “You never know what will grab you.””

Danny Funt

in Columbia Journalism Review

I'm a free range reader, as Larry McMurtry describes. I love Adam Gopnik's phrase "the great continuum of reading," but though I wander I'm not exactly an omnivorous reader. I have my interests, which vary from time to time, but I don't read everything. My selection process is a mixture of idiosyncratic searches and serendipity. In particular I've learned to believe in serendipity.

Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen is in part a memoir of reading by novelist and legendary book scout and book seller Larry McMurtry. I'm reading it now, and it is resurrecting and focusing memories of my own reading history that I'll probably be boring you with later in this space. But I am reminded that before serendipity was either a research technique or a selection process, it was a necessity. In the ignorance and restrictions of my early years of reading, I had to choose from what I happened to come across.

Since my retirement from, among other things, book reviewing, my reading has changed somewhat. Just for fun I've assembled books I've read (in whole or part) since January, to see where I've been roaming this year. (There are a few more books than pictured.)

The non-fiction books are fewer than fiction, which is itself a change. Jerome Kagan's

On Being Human is the second newest book in this pile, and the only one I got from the publisher as a review copy. Kagan had a long career as a research psychologist but is also thoughtful and erudite on larger issues of mind and the human spirit, as well as a trenchant critic of psychological research as it is practiced today. The first time through this book was to find those chapters and pages that most interest me, to which I will return. It's also one of those books that quotes other books that I immediately want to read.

Kagan is himself sort of retired now, and writing from that perspective. I'd read and reviewed

the book before this, which dealt more specifically with the practice of psychology, as well as an earlier book. So I was sure to read this one eventually.

Man and His Symbols is a classic work with a long essay by Jung (the last he published) and other essays by mostly first generation Jungians. This volume stands in for several others of Jung's I read parts of since the election, notably a volume of his collected works called

Civilization in Transition, with essays from between the wars and after World War II.

I had an old mass market sized paperback copy of

Man and His Symbols, and I carried it in my backpack on our Christmas trip to Menlo Park. What a great relief and pleasure it was to leave an awful attempt to make mechanistic and poorly designed psychological experiments into a theatrical experience, to sit in the sunny patio of a cafe, drinking coffee and reading Jung's chapter.

But after carrying it around with me since, the book's cover fell off, and its small size couldn't do justice to the many illustrations, reproduced in smeary black and white. So more recently I located a gently used hardback copy on Amazon and ordered that. It's one of those books that's probably going to disappear in a few years, so I just acquired some plastic book covers to preserve it. I'll keep the paperback--I like to open it at random at odd moments when I'm out and about, and usually I come upon something that strikes a spark.

Apart from memoirs, the only other nonfiction books I've read in the past few months are by digital revolution analyst and prophet Jaron Lanier, particularly

Who Owns the Future? Very smart, pretty dire.

This is a change from recent years, that I'm reading more fiction than nonfiction. It's also different from the preceding months as there are no plays in the pile, though I did read and enjoy a memoir by playwright David Hare,

The Blue Touch Paper. The trail I followed to that one was not entirely new--I got the DVDs of Hare's tv trilogy

Worricker starring Bill Nighy (films I'd seen before), and so looked at Youtube videos of interviews with Nighy and Hare that I hadn't seen the last time I'd searched. In one of them, Hare mentioned

The Blue Touch Paper. So once again, Amazon Marketplace.

Hare explains a number of things in this book but I came away still not knowing what "blue touch paper" means (had to google it.) I can tell you however that by far the dominant color in the Worricker trilogy (clothes, walls, landscapes) is blue.

The last time I committed to reading big long novels was in the 1980s, and they included

Gravity's Rainbow. It was however the only one I didn't finish then. I happily completed

Moby Dick, War and Peace and

Anna Karenina. But this year I did it--all the way through

Gravity's Rainbow, even following the plot. The style of Pynchon's sentences, his wonderful descriptions, were always attractive--I'd often read a few restorative pages over the many years since this novel first landed on my desk at the Boston Phoenix, when I assigned a reviewer for our first books supplement. Finally reading the novel whole was an accomplishment and a pleasure.

The other really big book this time was Dickens'

Bleak House, which I wrote about

here already. I got it off my own shelves, obviously bought used. I'm re-reading David Copperfield and will go on to

Tale of Two Cities (which I may or may not have read before) before tackling the massive

Our Mutual Friends, once I've had the adventure of acquiring a copy.

The newest book is Kim Stanley Robinson's

New York: 2140, a science fiction novel about surviving the climate crisis which I hope to write about in the future. I interspersed these and other more weighty volumes with some old science fiction written in the 1950s for teenagers, a genre which (again) I plan to write about here soon.

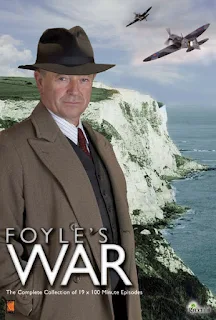

Also a Sherlock Holmes novel by Anthony Horowitz, who created and mostly wrote the

Foyle's War UK television series about World War II in the homefront.

House of Silk is a classic Holmes novel in style and subject, though with crimes Conan Doyle probably couldn't write about. I'd recently acquired the

Foyle's War DVDS with Horowitz interviews. It was mentioned that he published novels, so I looked him up on Amazon and found this one.

Flyover Lives by contemporary novelist and critic Diane Johnson is mostly about her childhood in a part of the country near where I lived for a time--Moline, Illinois, on the Mississippi River. I learned more about that area than I knew, and found similarities as well as differences in our childhoods and backgrounds. I got this particular hardback book at the local Dollar Tree--not the first or last I'm glad I scouted out there.

McMurtry laments the collapse of the antiquarian/used bookstore business. I've seen evidence of it--all the used bookstores (I remember 3) and the two or three new bookstores I knew on Murray Avenue and Forbes in Squirrel Hill, Pittsburgh, were gone in the first few years after I left in 1996, apparently done in at least in part by the big Barnes and Noble store that came in. Then the last time I was there, the Barnes and Noble was gone. (However, the Squirrel Hill Public Library on Forbes was greatly expanded, with a lot of computers but also more stalls of used paperbacks for sale.)

In Arcata in the late 90s there were four used bookstores; now there is one. The owners of two of the others continued to sell but only on the Internet. But there are other places now to find books, especially the thrift stores, of which there are many in Arcata and Eureka. I bought McMurtry's book at the Arcata thrift store run by the Humboldt Hospice organization.

There are still two used bookstores in Eureka, one of them also antiquarian. I trade books at the Booklegger in Eureka--they make the fairest trades--for credit on books there. That's where I found Sebold's

The Emigrants, which I'm now reading. I looked for it after seeing it praised in several different places within a week or two: serendipity. I'm glad I found it.

I heard Roy Parvin read once at Northtown Books in Arcata, when he lived in a nearby town and had recently published this volume of novellas

In the Snow Forest. I enjoyed the reading but couldn't afford the book at the time. I found a used copy later on and never got around to reading it until this month. The stories are well written and unlike anybody else's. I liked the first novella the best, although the second was the title story and the third--which includes a evocative description of a long train trip in 1957-- got made into a movie in Europe. So this one is an argument for keeping a library. Still, there was a certain serendipity in finding it---when I relocated a pile of books with little in common but that I'd long meant to read them.

My library held another interesting surprise. Before taking another look at Ford Maddox Ford's World War I saga

Parade's End, I thought I should read his more famous novel,

The Good Soldier (which has nothing to do with any war.) I looked in my tumbled fiction section and sure enough, next to several novels by Richard Ford, was a paperback copy of this one.

One of the delights of acquiring used books (including old library books) is the hints that previous readers leave. Not the manic highlighting--I can live without that. Sometimes just a name, a few notes, or a telling bookmark. I once had a first edition of

Gravity's Rainbow but sold it when I left Pittsburgh. Here I bought a used quality paperback--previous owner Joshua Wolf not only signed it, but left his United Airlines boarding pass stuck in between pp. 344-5. So I celebrated not only getting further into it than I had before, but far past Joshua as well.

With

The Good Soldier, this time the previous owner was known to me--an old girlfriend who evidently read it for her high school College English class, several years before I met her. (Along with her name and her familiar home address, she'd carefully written the name of the class and its teacher.)

That I had it in my collection--evidently for years--was a complete surprise. I haven't been in touch with her in decades but through her handwritten notes--probably based on what her teacher was saying--I found myself oddly communing with her teenage self. I was also reminded of how many of my college classmates had attended better high schools than I did. We didn't get literature beyond

Silas Marner and

Great Expectations at mine.

This pile of books doesn't include several I started but abandoned. One was a paperback from my shelves by Anthony Burgess, the English novelist with whom I once shared a deliriously liquid lunch. But the narrator was a man in his 80s, and I wasn't in the mood. However, the book's previous owner (Matt Hinton) left a wonderfully enigmatic message on the flyleaf: "The pelicans are flying in groups of seven today." Maybe he took "flyleaf" literally? That and his signature were all he left me.

Some of these books were discrete reading experiences, while others will likely lead to other books--by their authors, or mentioned in their pages, or on a similar subject, which in turn will branch in other directions. I picked out the Diane Johnson book because I recognized her name, and got it mostly because of Moline, but also because last year I read a couple of excellent memoirs that included childhoods in isolated areas of America--which started with the serendipity of finding one of them in a "free box:" cardboard boxes of stuff exiting students and other transients left behind on the sidewalk. (In another free box, I found a vintage paperback of the Isaac Asimov s/f classic,

I, Robot, which I hadn't read--but I will now. A book in the hand is worth two on Amazon.

In my free range reading, I don't know how much content I retain, but that's not as important to me as the reading experience, and the sense of things, the added depth and breadth, the connections and inspirations, the interplay with memories, of events and people and feelings.

So this is an account that suggests ways that books are in my life these days. (I wrote more about it now and again over the years, especially at my

Books in Heat blog, which by the way, has some paragraphs about a book in this pile I haven't mentioned--Don DeLillo's outstanding novel

Zero K.)

It probably isn't your typical twenty-first century story, but perhaps someone out there might be reading this and thinking, well I may be crazy but at least I'm not completely alone.