By the 1960s TV news

was growing up, at least to some extent.

The Camel News Caravan disappeared in 1956, replaced by the

Huntley-Brinkley Report, which became the dominant evening news broadcast on

television (though for awhile, the sponsor’s name appeared prominently on the

set.)

With this competition, CBS

replaced Douglas Edwards at the evening news desk in 1962 with Walter Cronkite,

who had co-anchored the network’s 1960 political conventions coverage with

Murrow. About a year later it became

the first half hour network news (fifteen minutes had been the norm), with NBC

soon following, and fledgling ABC several years later. Cronkite remained the CBS anchor until 1981, with his familiar closing: "And that's the way it is." According to polls, he became the most trusted news voice in America, and his on-air analysis of why the Vietnam war was failing legitimized mainstream opposition; "losing Cronkite" and hence much of America allegedly became instrumental in President Lyndon B. Johnson's decision not to seek re-election.

The early 60s team of Huntley-Brinkley (Chet Huntley reporting from New York,

David Brinkley from Washington) was famous for David Brinkley’s unconventional

speech pattern and wry takes on the news, and for the “Goodnight Chet,”

“Goodnight David” sign-offs. The first

Telstar communications satellite linking television transmissions from the US

and Europe in 1962 led not only to an outstanding hit record by the Toranados,

but a celebratory TV program with participants from all the networks—allowing

Walter Cronkite to say for once, “Goodnight, David.”

I was a big Huntley-Brinkley fan, and later when I did the

late night news on our college radio station with an expected audience of near

zero, I liked to amuse our station engineer by re-writing and reading wire

service news stories with the cadence and inflections of David Brinkley. Beginning with NBC’s coverage of the 1960

Democratic convention, NBC was my first choice network for news, the rest of

that fateful decade.

|

Grissom, Shepard, Glenn:

first 3 Americans in space |

One continuing news story of the 1960s was the US manned space missions. Launches of the first US manned spaceflights were covered live on television, and Americans learned to say "A-OK" and call the launch a "lift off" instead of the "blast off" of Saturday morning science fiction. I watched Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom on their sub-orbital flights, and then John Glenn’s three orbits of the planet, all described and shown (within fairly primitive technical limits) on live television as they happened. Later in the decade the Apollo missions were covered extensively, and the first human step upon ground not on Earth was seen (more or less) as it happened when Neil Armstrong stepped off the lander onto the Moon.

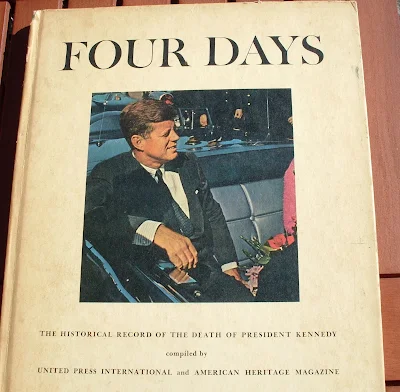

The Kennedy presidency, it was said, was the first

television presidency. The first-ever

televised debates of the 1960 campaign helped him get to the White House, and

his televised press conferences became viewing sensations, demonstrating his

knowledge of detail and his ready wit and ironic humor. Kennedy sat for long, thoughtful televised

interviews, with single reporters or groups of them in year-end

retrospectives. In these he talked

about the institutional and practical limits of presidential power, and the challenges

ahead—seminars in themselves.

I absorbed every scrap and pixel of information I could

about the Kennedy administration when I was in high school in the early 60s,

and almost felt I was part of it. (I can still recite the members of the JFK

cabinet, but not of any administration since.)

I had a world affairs column in the high school paper and maintained a

world news bulletin board in a classroom. It soon became impossible to ignore

that world anyway.

Thanks to an

official of the local political arm of the AFL-CIO who my friend Clayton’s

father knew, we got to attend President Kennedy’s only speech in Pittsburgh in

October 1962, officially as ushers.

Part of our responsibility was to alert Secret Service agents of anyone

acting suspiciously.

A few days later, President Kennedy saw surveillance photos

of Soviet offensive missiles in Cuba, and I was soon watching the Cuban Missile

Crisis unfold on television, along with the rest of the country. In school

one day I was reprimanded for being late to class, because I had stayed beside

a radio to ascertain whether Russian ships were going to fire on American ships

quarantining Cuba, giving us perhaps hours or even minutes before we would be

engulfed in nuclear war.

Months later in June 1963 I proudly watched coverage of JFK

giving his American University speech, which proposed the first break in the

escalation of nuclear weapons, the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, with an

eloquent case for the necessity of pursuing peace. Then the very next night I watched his

powerful nationally televised address

from the Oval Office on racial justice (carried by all three networks),

introducing the legislative ideas that would eventually become the law of the

land in the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts.

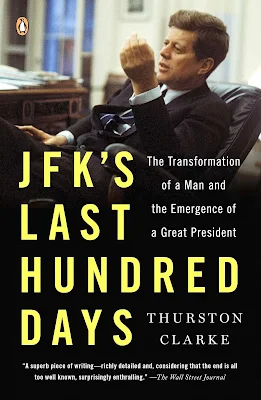

And then one November Friday afternoon in 1963 we heard

principal Father Sheridan’s voice announce over the public address that

President Kennedy had been shot. After the next school period I was walking up

the steps from gym class held outdoors, having almost forgotten about it, or convinced myself I would learn that he would be all right,

when a student going down to the locker room told me that the President was

dead. That day I knew my life and the

world around me would not be the same as it might have been, and I wasn’t

wrong.

To an extent it would be nearly unimaginable now, the entire

nation was in shock. There was nothing

on television that weekend except coverage of the assassination, the capture of

the suspect Lee Harvey Oswald, the preparations and then the funeral, with

retrospective footage of JFK. I watched

it all, almost every waking moment. I

couldn’t even be pulled away on Sunday to go to church with my family, and so

it happened that I was watching a live picture as Oswald was being

transferred. I jumped when I saw what I

thought was a gun, but I saw then it was a microphone (you can see it in this screenshot.) A moment later, a man rushed into the badly

lit black and white picture, the crackling sound of gunshots, a glimpse perhaps of Oswald grimacing and

crumpling, then rushed away, before I could be sure of what I saw. What I’d seen, however obscurely, was a man

murdered on live television.

Until then I’d accepted television as a given part of my

ordinary living. But that weekend in

November 1963 solidified it as a participant, wanted or not, in major moments

of what turned out to be my life.

By this time, I had served my short and tempestuous turn as

the freshman editor of the monthly high school newspaper (at least Edward R. Murrow

might have approved of me) and had joined speech club. After a couple of years

doing my best JFK style ex temp speeches on various topics (lugging file

folders of clippings and index cards down hallways of schools where we

competed), I went on to debate, partnering with my friend Mike Krempasky. We won

two district championships in our senior year.

Because of all this,

I was subscribing to and reading a lot of news and political issues magazines,

and haunting the periodical room at the Greensburg library, with occasional

forays to the college libraries at Seton Hill and St. Vincent. As well as keeping up with TV news,

commentaries and documentaries.

I was reading in other areas, following my nose in areas of

classic and contemporary literature. But these concerns with current events were regular activities. These

interests and passions regarding the issues that TV news

programs discussed to some degree, influenced some of the non-news television

shows I watched in the early to mid 1960s.

Once I started high school my viewing was more sporadic and

limited—I had more homework, debate research and preparation and other

extracurricular activities, and the semblance of a so-called social life

(mostly related to school—football and basketball games, school dances, band

concerts.) The speculative and melancholy mooning over girls took up their own infinities of time. So there were shows I watched when I found myself with the time and

inclination, but there were others that I made sure to watch.

There were two courtroom shows that featured characters that

would become all but unknown in television thereafter: idealistic defense

lawyers, fighting for justice.

The Defenders is the better known,

starring E.G. Marshall and Robert Reed, and written by Reginald Rose, a veteran

of live drama anthologies. It ran from 1961 to 1965.

The other is more forgotten now as it was obscure even then:

The Law and Mr. Jones managed just two seasons (1960-62) starring James

Whitmore as a modest fighter for the rights of the little guy, espousing

principles he quoted from Lincoln, Olivier Wendell Holmes and other greats. I didn’t know anyone else who watched this

series, and so it was my personal nurturance.

For a year or so, The Defenders and The Law and

Mr. Jones were both on, along with an early evening commentary show by

Howard K. Smith, one of Edward R. Murrow’s protégés at CBS who was fired for

expressing outrage at the conspiracy he’d uncovered between Birmingham, Alabama

police chief Bull Connors and the KKK to beat up Black civil rights protestors.

He moved over to ABC, where this commentary program was broadcast. I made sure to see it, and its tenor seemed

to fit into the same context as those two courtroom shows.

Beyond the courtroom, the struggle for social justice was

waged by social worker Neil Brock, played by George C. Scott in

East Side

/West Side. It ran for only one

season, beginning in the fall of 1963, but I saw every episode every Monday

night.

I was not only inspired and

excited by the passion that Brock/Scott brought to injustices and inequities

behind the tragic consequences he had to deal with as a social worker, but I

learned a lot as well. His partners in these efforts were played by Elizabeth

Wilson and the very young Cicely Tyson (the first Black woman in a featured TV

role, a few years before Nichelle Nichols.) James Earl Jones was among the guest stars.

Late in the series, Brock caught the eye of an ambitious

liberal Member of Congress in the JFK mold (played by Linden Chiles), and Brock

is persuaded he could do more good if he worked in his legislative office. But the process is full of compromise and

too slow.

|

| Cicely Tyson, Scott, Elizabeth Wilson |

As far as I can

recall, things were unresolved until CBS cancelled the show, sending the real life Scott on

an epic drunk (according to someone who had worked on the show I met years

later.) I met Elizabeth Wilson in the

1980s and told her of my admiration for the show. Also in the 80s, I saw George C. Scott in a production he also

directed of a Noel Coward play,

Design for Living at the Circle on the

Square theatre in New York. I was

seated on the aisle in the top row of the steeply raked auditorium, and Scott made his entrance

from just behind me—before I saw him, he shouted his first line directly in my ear. I was so stunned I missed most of the first act.

The coincidence of these three shows in particular (The

Defenders, East Side/West Side and The Law and Mr. Jones) during my junior

and senior years of high school, when I was engaged daily with some of the same

issues in interscholastic debate, were important to who I was becoming. Shows like those, that explore real issues

and model responses to them, are always rare.

The later years of Boston Legal came the closest to the approach

of those lawyer shows, and to my knowledge there’s never again been anything

like East Side/West Side. One series much later that dealt with social issues but from the perspective of reporters was Lou Grant, which also renewed that Monday at 10 p.m. appointment.

Viewing this combination of news, documentary and these

shows concerning the law and social justice, together with whatever impressions

I’d absorbed from those topical dramas from the Golden Age 50s, all informed

the scripts I wrote that won National Scholastic Magazine awards, the ones that got me my college scholarship. One of those scripts may have been a courtroom drama but the

one I more specifically recall involved Senate hearings. (Of course, of all the nonsense I saved from

those years, these scripts are absent.)

|

| Nancy Ames |

A somewhat related

show came soon after. I had already assembled some friends to enact my own

audio scripts of topical satire into a tape recorder when suddenly

(in January 1964, when I was still in high school) there was a television show

that did it all in a big way:

That Was the Week That Was, a weekly

satire on the news and culture, introduced by a song about that week’s events

to the theme tune, sung by Nancy Ames, on occasion her blond hair swinging as she gently

propelled her rotating office chair.

David Frost was the host, bringing a British edge to the

satire by a group of regulars, which included Buck Henry and Phyllis

Newman. Burr Tillstrom (Kukla, Fran

and Ollie) provided Emmy-winning puppetry, guest comedians included Nichols

and May, Woody Allen and Mort Sahl; Comden and Green provided their music, and

Tom Lehrer sang his subversive songs—so wildly popular later on campuses and

record albums—such as “The Dance of the Liberal Republicans” and of course my

favorite, “The Vatican Rag:” Genuflect, genuflect, genuflect. Other guests included Roscoe Lee Brown,

Steve Allen, Elliot Gould, Ann Bancroft, Alan Alda and Kim Hunter.

Mostly my viewing was catch as catch can: watching

Perry

Mason and

The Fugitive with the family, or a western (my favorites

were

Have Gun, Will Travel and

Maverick, but only when James

Garner was appearing.) The family

watched the

Dick Van Dyke Show sitcom, which I liked when I saw it

occasionally, and even more in syndicated reruns every afternoon in the summer. Though I appreciated some of its formal deadpan humor, I never took to

The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. Bob Denver's Maynard G. Krebs was funny, but I didn't dig him as a representative beatnik. I liked Tuesday Weld and Zelda. I just really didn't like the character of Dobie.

The one sitcom I made sure to see was Hennesey,

staring Jackie Cooper as a peacetime Navy doctor at a San Diego base

(1959-1962.) It was gentle, human and

humane humor, with a sweetly jaunty opening theme (which I can still

reproduce.) My old Dumont favorite

Roscoe Karns was Hennesey’s irascible superior officer, and I had a crush on

Abby Dalton, who played his nurse and love interest, and in the last season,

his wife. These were my teenage years, so in addition to everything

else I was listening to the latest music on the radio, following the top ten

and the “Wax to Watch” on KQV. I

watched American Bandstand after school, and Dick Clark’s Saturday night show,

as well as a local Pittsburgh version, “Dance Party” on Saturday afternoons

hosted by disc jockey Clark Race. I once saw him so apparently enthused by the

Marvellettes dancing and lip-synching to their new record, “Please Mr.

Postman,” that he had them repeat it twice more. (These scenes take on a

question mark with the revelations a few years later of payola.)

.jpg)

By now - after 1957-- television had videotape, and programs

were often, as they said, “pre-recorded.”

In addition to live interviews with kids and guests, and live dancing,

the music shows of Dick Clark and imitators featured singers and bands miming

to their records, before and after which teenagers danced to other records, and

some of them were selected to rate a new record. Their responses were almost always so much the same—“It has a

good beat. You can dance to it. I give it an A”—that they might as well have

been separately pre-recorded and inserted.

TV was moving farther and farther from live performance.

In the later 50s I had watched Your Hit Parade with

my family, in which a half dozen regularly appearing singers did versions of

that week’s hits. It had been an

important radio show, at one time featuring Frank Sinatra. But after 1956 or so, half the fascination

was noting the struggles that regulars like Dorothy Collins, Snooky Lanson and Giselle Mackenzie

were having with rock and roll tunes, until the program, like an old soldier,

finally faded away.

The early 60s made a

few attempts at live pop music programs but I wasn’t grabbed by any of

them. For a year or so there was Hootenanny

to feature the folk music boom, but it never had very prominent acts. Years later I learned the reason: the show

was incredibly still obeying the Blacklist fears of folk performers like Pete

Seeger, and because of that, the stars of the day like the Kingston Trio and

Peter, Paul and Mary refused to appear.

There were a few shows that everyone I knew at school

watched and would talk about. One was

The

Twilight Zone, especially its first few years. I can recall several of those shows even now, as probably others who saw them can. Nuclear apocalypse was a frequent theme.

Later there was 77 Sunset Strip, with its finger-snapping

theme song, Kookie the hip parking lot attendant, and some decent detective

stories with stars Efrem Zimbalist, Jr and Roger Smith.

But in my high school there was one show that was wildly

popular, at least among the students I knew, even though watching it would seem

imprudent if not impossible, because it didn’t end until one in the

morning.

It was the latest iteration of the Steve Allen late night

show. No one disputes any longer that Steve Allen created the template for late

night shows with the program he refined for local New York City audiences that

NBC broadcast nationally as The Tonight Show in 1954. At the same time he hosted a Sunday prime time variety show,

which by the early 60s had moved to Monday and then Wednesday nights. When that show ended, he immediately

returned to late night.

This show was produced through Westinghouse Broadcasting,

and it so happened that its flagship station was KDKA-TV in Pittsburgh (the

former Dumont affiliate as WDTV), so we had the opportunity to see it. It was broadcast from an old vaudeville

theatre in Los Angeles, rededicated as the Steve Allen Playhouse.

I was too young for the Steve Allen Tonight Show (or

for his successor Jack Paar), but I was a big fan of his Sunday show. The Westinghouse late night show was even

wilder. Allen was a bundle of

intellectual energy with a surrealistic edge. Sitting at his desk sipping orange

juice, he theorized that some words were innately funny, because of their

sound. Three of his candidates were

“smock,” “fern” and “creel.” Thereafter he might punctuate whatever he was

doing by suddenly shouting “Schmock! Schmock” like wild bird cries, or

seriously ask a guest, “How’s your fern?”

His fascination with words led him to play Mad Libs (filling in the

blanks of a narrative with random words, and then reading the result) with his

audience.

Jay Leno later

called Steve Allen the first modern comedian without vaudeville ties and

schtick, but as this show proved he was also adept at creative and outrageous

physical comedy as well as satirical skits and wisecracking commentary

befitting the best vaudevillians. One

of his regular offbeat guests was the health food advocate Gypsy Boots, who

entered by swinging across the stage on a vine.

What Steve Allen could do that no other late night host did was play piano with his band and musical guests (mostly jazz)--and he did this frequently. He was also a composer, and would challenge audience members to give him three or four numbers corresponding to notes on the keyboard, and he would use them to compose a song on the spot.

When I interviewed him in the early 1990s in Los Angeles I

referred to this game, though I suggested he used letters. He corrected me, saying he used numbers.

Until we were backstage at the 40th anniversary Tonight Show (his

last appearance, as it turned out) when he was chatting with comedian Phil

Hartman who referred to the same bit, and also thought it was letters—so a

thoroughly confused Allen mumbled, sometimes numbers, sometimes letters. But much later I realized the source of my

mistake—I had borrowed the bit in high school to dazzle female classmates,

substituting letters in their names that matched keys for numbers to compose a

rudimentary tune on the piano.

The show was so popular with my contemporaries who really

shouldn’t have been up that late that the class ahead of mine selected the

Steve Allen Show as the theme of their class variety show, with Jerry Celia at

a desk wearing his Steve Allen glasses, orchestrating the music and mayhem,

including the patented Gypsy Boots entrance.

This iteration of Steve Allen’s show—and a late 60s

revival—were often cited as inspirations for the next generation of late night

comics, including David Letterman, who shamelessly stole many of Steve Allen’s

bits—that is, the ones Johnny Carson wasn’t already doing on the Tonight Show. I remember as well that late 60s revival, being home from college

in the summers and waiting all day to watch it in the silence of late

night.

In the fall of 1964 I went off to Knox College in Illinois

(carrying with me the Kenyon Hopkins album of his jazz compositions for East

Side/West Side, and an LP of Steve Allen leading a jazz band, Steve

Allen at the Roundtable.)

While

there I won a national college writing prize, again with a television script,

but I never had a TV set. I

occasionally watched something on the big console in the student union (

Star

Trek, the Monkees) and caught some reruns in the summers (those same shows

plus

Get Smart, The Man From U.N.C.L.E), but during the school year

there was far too much else to do, and other claims on my attention.

Ironically perhaps, this was also when I became besotted

with the writing of Marshall McLuhan, who proclaimed that television heralded

an entirely different view of reality.

His insistence that the importance was not in the programs but in the

medium itself was new to me, and pretty much everyone else.

The only television show I associate with college was a few

months of gatherings at a student apartment (either James Campbell’s or Bob

Mizerowski’s) to watch the campy Adam West

Batman series, after which we

went out on the lawn to toss around a Frisbie (then also new and hip.) Most of network television seemed dismal:

the vast wasteland.

Television’s potential power began to be felt immediately in

the 1950s, but as television grew, it was the decade of the 1960s that opened

more eyes to its still unfathomed cultural, societal and political influences

and impacts. John F. Kennedy was said

even at the time to be the first television President, and Vietnam was the

first television war (or “living room war” as it came to be called.)

But the profound and even shocking effects on political life

and power became more striking and more ominous in 1980 when Ronald Reagan,

known nationally as the genial host of television’s

General Electric Theatre

and

Death Valley Days (brought to you by Twenty Mule Team Boraxo)

was elected President. Before that,

Reagan at least had two terms of government experience as governor of

California. But in 2016, a man with no governing experience on any level was

elected President, his self-created caricature of an image having been

burnished and elaborated on a nationally popular television reality show. There’s a detailed study to be made

comparing his campaign and presidency played on television, with the radio rise

and reign of Adolf Hitler.

Before the decade was out, television would make me witness to Vietnam and the antiwar demonstrations I didn’t attend personally, student

uprisings on other campuses, and the out-of-body moment when we heard LBJ announce

he would not run for President again (which at the time seemed to promise an

antiwar candidate.)

And more than a witness to horrors of Martin Luther King’s

assassination aftermath, and especially Robert Kennedy—the speech in Los

Angeles after he won the last and biggest primary of all, and hours later the

news of his being shot, then many hours, days and nights, of the deathwatch,

then the funeral and the funeral train. The coverage became surreal as reporters tried to find interviewees and so on to fill the time while Robert Kennedy's life was still in question, and one of the remaining unknowns was the alleged assassin Sirhan's first name. I watched NBC's Sander Vanocur, on the brink of physical and emotional exhaustion, try to report the breaking news answer with objective gravity: his first name was Sirhan. He was Sirhan Sirhan.

Then that summer the Democratic Convention and televised police riot in Chicago, cops smashing clubs on protesters, with witnessing crowds then chanting (for the first time): The whole world is watching!

Even without these associations, I was more repelled than

attracted by television in those years.

In the later 60s, as countercultural pursuits emerged to absorb my

attention and alter my focus, television programs seemed even more out of

it. Laugh-In and The Smothers

Brothers Comedy Hour were of some interest, but at least for a time, it

seemed that while I’d grown up with television, I’d now outgrown it. But there would be more to it than

that.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)