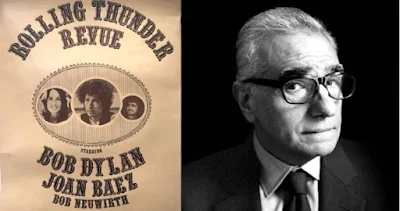

The other night we watched the new Martin Scorsese film on Netfliks:

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story. I came to it with innocence and curiosity. I vaguely remembered reading about Dylan's Rolling Thunder tour in 1975-76, and seeing photos of him with heavy eye makeup and in whiteface. I was still pretty current on the music scene, being in what now historically was the first generation of rock critics, but Dylan was not central to that scene anymore. He was mercurial, changing faster than anyone could follow, and yet a little too familiar. He would soon lose a lot of cred during his Jesus phase, though his 1974

Blood on the Tracks album was clearly one of his best. But before we all could absorb it, he changed again with his next record,

Desire.

So just about all I knew about the Rolling Thunder tour was what I read in the music press at the time, principally Rolling Stone. (The only other element I recall is the impression that there'd been ample cocaine use, pretty common in the mid-70s. Some of the footage here does nothing to dispel that notion.) So I was very interested to see and especially hear what this tour had been about.

The music does not disappoint. Dylan was absorbing influences a lot of us were not ready to hear at the time, including perhaps the gypsy violin of Scarlet Rivera. His radically different takes on his own old songs were sometimes jarring then, but hearing them now, they are bracing and revelatory. Perhaps the most surprising element is how good his singing is; it was never better, before or since, especially in the range of styles he employed. There were

Blood on the Tracks style renditions, very bluesy or rock or jazz renditions that took liberties with the melodies no one else could get away with.

The basic format of the tour was to assemble players, some of whom would have solo spots in the show, and to play smaller venues. Eventually the tour would include performances by Joni Mitchell, Roger McGuin (the Byrds), and (not shown in the film) Robbie Robertson. Dr. John and Stevie Wonder, plus regulars like Ramblin Jack Elliot and country rock singer Ronee Blakely.

Joan Baez was on the whole tour, and her participation is a highlight of this film. All the Joan and Bob angst of

Don't Look Back and Scorsese's previous Dylan biopic has disappeared. She sings duets with Dylan, dresses up and cavorts and dances onstage. She was never more beautiful. Poet Allen Ginsberg is also a positive presence throughout.

The stagecraft is unusual, and this film gives various reasons for it. The one that makes the most sense was an attempt to adopt a Japanese Kabuki theatre style, with the makeup and the exaggerated formal stage gestures, like the incredible stares Dylan does, or that he and McGuin do at each other in the final number shown in the movie.

But this brings me to the problem that not only spoils the movie for me, but causes me to condemn it. When the film was over, I thought I'd come to understand something about this tour. There were some contradictions, and even in present day interviews, Dylan was being Dylan and contradicting himself--the sincere put-on seems a habitual part of his public personality.

But a few things confused me. I was particularly bothered by an interview towards the end of the film, in which a supposed Member of Congress in the 70s spoke at length about how President Jimmy Carter got him in to see one of the Rolling Thunder performances. It was otherwise a pointless story. I recognized the man as an actor--I remembered him especially from a Robert Altman film--but of course actors do run for office, and maybe he had.

It was only after looking up information on this tour and Wikipedia's short piece on this film that I learned that significant elements of this Scorsese film were entirely fictional. In other words, a lot of it was comprised of lies.

The supposed filmmaker, the promoter of the tour are fictional; actress Sharon Stone appears, relating how she became part of the tour as a teenager, and present-day Dylan talks about her, but none of that actually happened. (I'd wondered about this, knowing that she was from my part of the country, not New England.) And that actor--Michael Murphy--was playing a politician he had originally played in a 1970s series. He'd never been in Congress. His pointless screen time was also false.

It's become pretty standard for biographies, autobiographies, memoirs to follow the practice of Hollywood films about well-known people (usually dead) in creating composite or fictional characters to collapse a life into a more classically shaped story line. This is more dangerous when the story is not being re-enacted by actors who clearly are not the real people, but it is a trend in print as well as on film. In that regard, the character of the promoter is excusable, provided that he is expressing views and experiences of the actual promoters.

But I do not find the other deceptions remotely excusable. The politician was merely pointless. But the others deceived viewers on major points, and obscure actual understanding of the Rolling Thunder tour.

In the back of my mind I associated this tour with

Renaldo and Clara, though I couldn't remember whether that was the name of an album or what. I did recall it involved Dylan in role-playing. It turns out that it's a movie that Dylan and his first wife Sara starred in, that lists Dylan as the director and writer, and that was shot during the Rolling Thunder tour. It also may have been the major reason for the tour itself.

That film--originally four hours, cut down later to two--has hardly ever been seen. There are hazy bits of it on YouTube. Sometimes when a film (or other work) meets with failure at first, it gains new respect later. That's not the case with

Renaldo and Clara, at least not yet. (Apparently it got a better reception in Europe.)

But this movie is never mentioned (and neither is Sara, to my recollection) in the Scorsese film, and it seems that the deceptions are designed to draw attention away from it.

That's a bit ironic, in that film historian Scorsese might have been interested to explore how

Renaldo and Clara relates to its alleged model,

Children of Paradise, a 1945 French language film by Marcel Carne. It involves members of a 19th century theatre troupe in love with the same woman. Observers note several similarities between this film and Dylan's, notably the use of whiteface--one of Carne's main characters is a mime.

|

| Faked photo placing young Sharon Stone with Dylan |

If indeed the tour was mostly a setting for a fictional film, and especially if this French film is the inspiration for whiteface and the other makeup and costumes--a possibility never mentioned in the Scorsese film--then the elaborate lies the Scorsese film tells about the origin of the whiteface (including a Kiss concert Dylan is said to have attended, which he did not; the concert itself didn't exist) is intentional dishonesty, and unforgivable.

So are the Sharon Stone sequences--including a composite photograph to show her with Dylan-- which seems to have no purpose other than to further obscure the reason for the whiteface. In particular, it attributes to Dylan a depth of knowledge about Kabuki that he may not have had. (Though indeed he might have--Dylan had traveled a lot and knew a lot about American and world culture. Certainly more than I did in the 70s.)

|

| The fake director |

One of the most compelling characters in the Scorsese film is the fictional filmmaker who supposed shot all this footage. In fact the footage was shot at Dylan's direction for

Renaldo and Clara. Though that film is never mentioned, there are some possible in-jokes referring to it in the Scorsese film. In snippets of interviews, several tour participants refer to Allen Ginsberg as a kind of "father figure." (The present day Dylan contradicts this.) The character Ginsberg played in

Renaldo and Clara was called the Father.

Here's the larger problem: because all this footage was shot for the fiction film

Renaldo and Clara, any and all of it from the tour could be fiction. That includes two of the more affecting scenes: one a conversation between Dylan and Baez, and one a conversation between Dylan and Ginsberg at Jack Kerouac's grave. I can no longer believe them. Not only might they have been scripted for a different movie, they are not even seen in the context of the movie they were intended for: a double lie.

This falseness extends to the present day interviews. In them, Dylan talks about the fictional characters as if they were real, and about Sharon Stone as if she had actually been on the tour. Others make similar comments. Now I can't believe anything they said.

Once the fakery is known, how are viewers supposed to respond, especially if they didn't live through the 1970s? Do they wonder whether there really was a Hurricane Carter, who was wrongly imprisoned for murder, or was he just a character that Dylan made up for a song, portrayed in this movie by an actor? (Unfortunately, the footage of President Jimmy Carter giving his earnest and silly interpretation of a Dylan song is probably real.)

|

Cate Blanchett as Dylan in

I'm Not There |

It's one thing to do a film about Dylan in which he is played by various actors, including a woman (as Todd Haynes did with

I'm Not There. A useless movie in my opinion but still, legitimate.) That's a pretty clear signal to viewers to take the supposed biographical information with a grain of salt.

But this is a film by a noted filmmaker who has established a record of going from clearly fictional films (however based on actual people and events) to documentaries--in particular one of the best concert films in

The Last Waltz and then the later Dylan biography,

No Direction Home and the excellent George Harrison biography,

Living in the Material World. Other directors, like Michael Apted and Jonathan Demme, have done the same. This distinction is what the public now has the right to expect, unless clearly told otherwise.

Despite the excuse in the subtitle--A Bob Dylan Story--this film has all the usual features of a documentary, that may take the usual liberties of such films but is essentially fact-based, and certainly does not elaborate falsehoods. It is not a reenactment--it features the actual artists and actual concert footage and so on. It is natural that viewers take this as truth--by the evidence of YouTube videos that pass on some of its falsehoods as truth, at least some viewers have. But there is nothing trustworthy in this film.

It turns out I'm not the only one to react this way. A

Variety reporter at an event after a premiere wrote this:

"It wasn’t hard to gauge the reaction, since in just about every case, when I asked people what they thought about the fakery, that was the very first they’d heard of it. (Unless you have extra sensory perception, you’re going to buy what this movie shows you.) Most of the people I spoke to were wide-eyed with disbelief yet kind of bummed. Over and over, they said that they felt duped, suckered, maybe even a little betrayed. Of the 20 or so people I had conversations with, not one said, “Really? That’s kind of cool!” The fakery left no one with that Andy Kaufman feeling of awe. And this was a crowd of people who were disposed to like the movie, many of them with two or three degrees of separation from Martin Scorsese."

And here for me is the money quote from this reporter about the director's deception:

But the way he does it, as a friend of mine said, “It seems more Trumpian than Dylanesque.” Perhaps we are a bit more sensitive to lying now, but we have good reason to be.

If I were still a rock critic (and if there still were rock critics) and got the freebie box set of music performances from the tour and a disk of this movie, I would toss the movie aside. Only the audio recordings can be trusted.

"Art is the lie that tells the truth," Picasso famously is said to have said. This film just lies. Does that make me Mr. Jones? Possibly. Or maybe I believe more than I did in respecting the audience as a matter of principle, or at least respecting the form. I certainly feel disrespected as a viewer, and offended as a writer. This is no direction home.