But I do more or less keep up on the fate of the planet from global heating, species extinction and other tragic destruction of the natural world that sustains all life, including ours. And there the news in 2019 could hardly be worse. The insane policies of the current US regime are beginning to take a severe toll on the nation's laws and policies, and perhaps most obviously on the world's will to address the climate emergency, as evidenced by the virtual collapse of the recent UN climate summit.

Lack of US leadership, or even encouragement in the wrong direction, has emboldened the government of Brazil to allow the cynical burning and cutting down of vast areas of the Amazon rainforest, which is not only causing severe degrading of air quality and other problems in the vicinity, but which adds to the load favoring global doom. Add this to relentless and expanding effects of melting at both poles, and any chance of saving the future seems more and more remote.

All of this is fueled by global social conflict leading to a growing imbalance in the human response to almost everything. The dark side of human nature is in the ascendancy: greed, hate, systematic and reflexive mendacity, willful ignorance and an almost inexplicable cruelty.

So 2019 was not a good year for the world and many people in it, and a potentially catastrophic year for the future. Except for important reductions in severe poverty, and what now seems like the distant memory of the Obama years, there's little better to say about the entire decade.

As for those prominent people I knew of but did not necessarily know who died in 2019, when looking at the long list of them, I see my own world slipping away as well. These were people who populated my life in some way, and as I have waning interest in (or access to) a lot of current culture, they are not being replaced. This is part of getting old, and realizing it is part of dealing with the change. But it's also true that the world is changing in ways it hasn't changed in generations--the ways we typically get the news, for example.

When I read some of the names, I recall first my experiences with these individuals, however brief. James Atlas was a writer, editor and publisher I encountered a few times when we were both young men in Cambridge and Boston in the early 1970s, and had friends in common. Even then he was working on his biography of the American poet Delmore Schwartz that was nominated for the National Book Award, and complained that Schwartz was invading his dreams. My most extended memory is of an evening when the two of us detached from a larger group to go bar-hopping, and got gloriously drunk together.

I interviewed architect Cesar Pelli in the 1970s, when he was chiefly a designer of shopping malls (including Greengate Mall in Greensburg.) He was a key voice in my "Malling of America" article for New Times and subsequent book. His pronouncement on the mall's effect ("Towns disappear!") was an influential eye-opener at that early stage in my research. He later became a prominent architect indeed of major urban projects in New York City and around the world. I remember him as gracious and thoughtful. (And in these photos, he looks a lot like James Atlas.)

|

| Wofford accepts the Presidential Citizens Medal from President Obama in 2013 |

I also recall that at one of our Job Center inaugural events, Wofford asked everyone not to use the increasingly common jargon of "servicing" people. We service machines, but we serve people, he said. This respect for language impressed me, as did his urbane and--yes--Kennedyesque manner. Later he was elected to the US Senate as a prohibitive underdog, the first candidate to demonstrate the political potential of running on expanding health care coverage.

Among the musicians of my time who died in 2019 (including Ginger Baker of Cream and Peter Tork of the Monkees) I remember a more obscure one: Leon Redbone. I saw him perform at a small club in Cambridge, from the front table reserved for music writers. He wore dark glasses and a broad-brimmed hat, and kept his head down so we hardly saw his face, as he played acoustic guitar and sang one old standard after another in his rich baritone. It was the strangest performance I'd seen to that point. Still, I got several of his records, and I always hear "My Blue Heaven" in his voice.

When I met Tom Ellis in the WBZ television newsroom in Boston in the early 70s, a lot of people didn't know what to make of him. With matinee idol looks and a sometimes uncertain grasp of words, it seems to some he was a model for Mary Tyler Moore's Ted Baxter. But his newscasts led the ratings by a lot, and he hung in there, learned his craft, and stayed on the air for the next 30 years or so. For awhile he kept jumping stations for more lucrative contracts, and everywhere he went became the top news station. He was the only person in Boston ever to anchor number one news broadcasts at all three network affiliates. After a stint in the Big Town of New York, he returned to Boston to anchor for another 14 years. I can't say I got much of an impression of him, except that he was not arrogant or manipulative. He was genial and hugely enjoyed what he was doing.

Speaking of the future, my research for magazine articles in the 70s on the subject brought me in contact with futurists Wendell Bell and Barbara Marx Hubbard. Hubbard, as heir to the Marx toy fortune, was a kind of godmother to young futurists, kind and careful and probably rightly suspicious, though in a gentle, tentative way.

Others I never met, I remember in their historical moment. Writer Dan Jenkins and screenwriter Christopher Knopf were making a big noise (as Anthony Hopkins might put it) in the 1970s. Actors Anna Karina, Peter Fonda, Sue Lyon, Danny Aiello, Valerie Harper, Rip Torn, Peggy Lipton, Carol Channing, Phyllis Newman, Carol Lynley, Michael J. Pollard, Rene Auberjonois, Rutger Hauer, Bruno Ganz and especially--over some 50 years-- actor Albert Finney populated the collective dreams of my era known as movies and television.

One of my favorite Finney films was Two for the Road with Audrey Hepburn (1967), directed by Stanley Donen, who also died in 2019. Donen had also directed the 1950s classic musicals On the Town and Singin in the Rain (which I've only learned to appreciate years later), the 1957 comedy Kiss Them For Me with Cary Grant (which I discovered on TV); the 1960s caper films Arabesque and Charade, the Peter Cook and Dudley Moore comedy Bedazzled (all of which I saw first run at theatres). All of them fondly remembered.

The lovely Julie Adams lit up odd movies like Creature From the Black Lagoon and Francis Joins the WACs, but her long career confirms her acting talent and intelligence. Franco Zeffirelli caught the 1960s youth spirit with his Romeo and Juliet. Dusan Makavejev made one of the strangest yet most compelling movies of the 1970s with WR: Mysteries of the Organism.

I had perhaps as many arguments as agreements with Harold Bloom's work, but I honor his reverence for literature. Ward Just and Larry Heinemann were among the writers first ruminating on the Vietnam War after it was over. Paul Krassner was a provocative and often funny presence in the 1960s. Ram Dass was his more spiritual counterpart.

|

| Sander Vanocur with RFK |

And that's the paradox of mourning these deaths: they are so bound to moments of my past, with no likelihood that there would be such presence in my future. In a sense I lost them long ago. Their moment is fixed in time forever, yet their definitive passing still seems to depopulate my world.

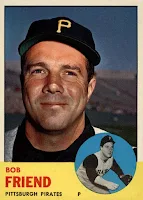

So I mourn Joe Bellino, possibly the first football star (for Navy) that I recall by name from my youth, and Bob Friend, the oddly colorless ace pitcher for my beloved 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates, whose record for the most innings pitched in a Pirate uniform is unlikely to ever be broken. (Rex Johnston also died this year--I don't recognize his name, but he has the distinction of having played for both the baseball Pirates and the football Steelers.)

Other once-important names float through my journalism days memories--Harold Prince, Eliot Roberts, Robert Evans, Andre Previn... Their accomplishments are recorded, but some fame is fleeting. Ross Perot was once one of the most important people in the US--he was the first billionaire who ran for President in 1992 as an independent and might have won if he hadn't dropped out and then reentered the race. He ran again in 1996, and both times got more votes than nearly any other non-R or D candidate. Though he was a Texan, my hometown of Greensburg, PA bragged that he'd married a local girl, with the wedding in Greensburg itself. But his death in 2019 was barely noticed, and his name didn't generally make the "notable deaths" lists.

|

| Lee Radziwill |

May they all rest in peace. Their work and their memory live on.

So with their passing in 2019, my world inevitably and inexorably got smaller. These figures in the ground of my life leave me in a world of noisy strangers who can't understand me, or perhaps even see me, the Mad Hatter presiding over a phantom tea party, spouting nonsense. I am left to live and grow and change--quite happily-- among the fixed stars of the past, and above all in the near and present.

And what's that up ahead? The first hour of a new year.

Note: In addition to previous posts here on Ric Ocasek and Jonathan Miller, I've posted on writers who died in 2019 at Books in Heat, and on Star Trek and Doctor Who related deaths at Soul of Star Trek.