|

Jerry Siegel was 20, the son of poor immigrants in Depression Cleveland, searching for ideas for a comic strip character that he and his friend Joe Shuster could sell to newspaper syndicates. Grabbing elements of characters and how they looked from other comics, B-movies and science fiction pulp magazines and novels, he added some unique features to his choices.

In the 1890s H.G. Wells reversed the usual plots in scores of forgotten Mars stories: instead of sending humans to Mars, he brought Martian invaders to Earth. Siegel made a similar move. Instead of a hero like Edgar Rice Burrough’s John Carter whose exploits took place in the strange societies of Mars, Seigel brought the strange visitor from another planet to the familiar streets of everyday life on Earth.

As the ultimate illegal immigrant from outer space, he could have powers and abilities far beyond those of ordinary humans. But to mix with humanity he would need a secret identity: somebody that didn’t look like a superhero, somebody—like Siegel and Shuster—who wore glasses.

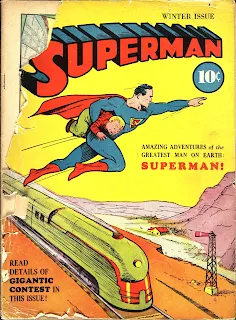

They talked about how Superman should look and Shuster drew him with the signature S on his chest. The costume was futuristic, like Flash Gordon, but it also made his powers coherent to his 1930s audience. For where did people see beings of immense strength, who could leap through the air, and had other powers bordering on the mystical and magical? Only one place: the circus. So Superman had the aerialist’s tights, the underwear on the outside of the circus strongman, and the magician’s cape.

But Superman was a Depression product in a more profound sense. In 1934, when Siegel first started dreaming up the character, he was influenced (as he later recalled), by “President Roosevelt’s ‘fireside chats...being unemployed and worried during the Depression and knowing hopelessness and fear. Hearing and reading of the oppression and slaughter of helpless, oppressed Jews in Nazi Germany...seeing movies depicting the horrors of privation suffered by the downtrodden...”

Siegel was also reading about crusading heroes and seeing them in the movies. He wondered how he could help these victims of the 30s. “How could I help them, when I could barely help myself? Superman was the answer.”

This became the key to Superman’s character that has endured many reductions and perversions over the years but has somehow survived. His first adventure in Action Comics involved saving an unjustly condemned woman from the electric chair. His next was stopping a wife-beater.

According to author Thomas Andrae, Superman was “neither alienated from society nor a misanthropic power-obsessed nemesis but a truly messianic figure...the embodiment of society’s noblest ideals, a ‘man of tomorrow’ who foreshadows mankind’s highest potentialities and profoundest aspirations but whose tremendous power, remarkably, poses no danger to its freedom and safety.”

Superman became so immediately popular that barely more than a year later, he appeared at the New York World’s Fair and his huge balloon image flew over the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade.

Just two years after that first comic book story, Superman was the star of his own radio show, and a year after that, he was the star of the first animated adventures shown in movie theatres in the ground-breaking Fleischer Studio cartoons.

|

| from the 1940s Fleischer animations |

But radio and the animated cartoons added new characters (Jimmy Olsen, Perry White) and elements (kryptonite), including Superman's ability to not just leap tall buildings in a single bound, but fly.

Still, the original impetus for the character of Superman remained. Versions of the opening made famous on television began in radio, but with significant additions. On the very first radio broadcast Superman was described as "champion of the oppressed...who has sworn to devote his existence on Earth to helping those in need."

Later on radio he would be described as “ champion of equal rights, valiant, courageous fighter against the forces of hate and prejudice.” In 1946, a 16-episode series had Superman battling an organization based on the KKK ("The Clan of the Fiery Cross.") Reputedly based on descriptions by an actual reporter who infiltrated the Klan, it exposed its secret rituals as well as its crimes. The series was credited with reducing KKK recruiting. Notably, immediately after the war, it related this domestic racism to Nazi racism.

Of course, Superman also foiled bank robbers, defeated and deflated mad scientists, and rescued people, Lois Lane in particular.

Two mostly live action serials (the flying was animated) for movie theatres came next, with Kirk Alyn and a young and especially fetching Noel Neil as Lois Lane, a role she reprised in all but the first season of the 1950s Superman TV show.

Television was the next natural step, so just as Action Comics pioneered the fledgling field of comic books (only four years old in 1938), The Adventures of Superman starring George Reeves was one of television's first major hits. But producers first tested the waters with a 1951 theatrical release, Superman and the Mole Men. The mole men were probably unintentionally comical looking little beings who lived deep under the Earth, with a few of them emerging from the deepest oil well shaft ever sunk.

|

| from Superman and the Mole Men, seen also as episodes in the first season of the TV show |

The syndicated TV show itself premiered with its version of the Superman origin story in 1953. I was six years old and happened to see it when it aired one Saturday afternoon on a Pittsburgh channel.

|

| a Kryptonian in the origin episode |

Afterwards I hastened to my room to think about it. I wasn't sure what I'd just seen, and nobody else was interested. The girls were engaged in their frenzy of shrieks and running, while my mother was inaccessible in the kitchen with her guest-- If I ventured in, they would either ignore me or, even worse, talk about me as if I wasn't there.

So alone in my room I made the classic kid move: I tied a blanket around my neck and trailed in down my back as a cape.

|

| George Reeves and Phyllis Coates, who played Lois Lane in the first season |

But I did not want to keep my true identity secret from a blond girl named Judy, and once stood outside the classroom where I knew she was, significantly glancing to the sky and running off, George Reeves style, to transform into the Boy of Steel. I somehow believed she would interpret my actions correctly.

I fell deeply into every second of those stories every week, especially the first two seasons. I have the series on DVD and the opening sequence still had an indescribable effect. The first season had the same producer as the radio show, and both the stories and the style seem derived from radio but also the noir aspects of the Fleischer animations and the movie serials, themselves influenced by crime and suspense movies.

The Adventures of Superman was also an immediate hit, but since it was a favorite with children, a new producer was hired for the second and subsequent seasons who eliminated its moodiness and crime movie violence, and skewed the stories more towards kids (and the approval of meddling congressional committees.) Still, the second season began with the first comic book plots--Clark Kent proves a man convicted of murder is innocent, and Superman saves him from the electric chair.

Beginning with the third season, the TV show was filmed in color. There were no color televisions yet so these shows were first seen in black and white. That accounts for the fact that the characters were all dressed mostly in blue, which transferred to black and white best (and because the shows were shot quickly, often scenes mixed and matched from several episodes at once, the characters tended to have the same basic wardrobe.) But when color TV sets became possible and popular in the 1960s and 1970s, reruns of the last four seasons of Superman got new life for several more generations.

Most of the memorable episodes are in the first two seasons, but even within the rote plots of the last seasons there are delightful performances and surreal comic moments, as when one thug fantasizes about what he will do with his cut from his gang's robberies: he'll build a big house shaped like a penitentiary so his friends will feel at home.

Under the spell of the TV show, I sent in for my membership to the Supermen of America Club. I got my letter, membership card, button and the secret code, which I remember as a colorful grid rather than a cardboard wheel. There were actually nine different codes, one for each planet. They were for secret messages in the comic books. I kept the codes between my mattress and springs.

The button image, by the way, shows Superman breaking chains--another throwback to the circus strongman. But the motto--strength, courage, justice--was all Superman.

The button image, by the way, shows Superman breaking chains--another throwback to the circus strongman. But the motto--strength, courage, justice--was all Superman.Superman fell on hard times for decades after that. The comic books got more fantastic--thrilling in their way for awhile, but then downright silly. Superman's powers grew to an absurd extent, and so he required villains with their own extraordinary powers, usually matched by motives of revenge or wanting to rule the world (or the universe.) This is the same superhero syndrome we've got today. So I look back to the otherwise awful episodes of the 1950s TV show to see at least a human scale Superman, who helps those in need.

Superman was also treated as a joke (on Broadway and a short-lived TV show as well as the comics) and then with cynicism and derision. He wasn't hip or relevant, he was square and establishment and obsolete. His story was twisted, he and his Earth parents were given cynical motives, his myth seemed outworn and false.

Then in 1978--exactly 40 years ago--Superman came back.

To be continued...