I remember for certain that I showed him the first short story I wrote at Knox. I'd read somewhere--probably in Writing Fiction by writer and veteran teacher R.V. Cassill (the only such book I owned)--that stories are told in either the first or third person. Almost no one had adopted the second (or "you") person. So naturally, for my very first college story, I chose to try it.

It was an interesting exercise but it's clear why it's so rare. It did create a certain impersonal tone, suggesting a narrator trying to keep a distance from the emotions evoked by the events in the story, while enabling stark expression of those emotions. Though I doubt I was aware of this at the time.

The subject was leaving home for college (it became a source for details I included in a previous post about that first trip to Knox.) Mr. Moon honored the feeling, the importance of the feelings in the story, while gently and sometimes bluntly pointing out its many flaws and especially the worn-out expression which I had absorbed from the Reader's Digest and another popular sources, which I was just learning to disdain.

Sam Moon taught poetry writing and play writing (he himself was a poet published in the most respected journals, and edited a book of classic one-act plays.) The professor who taught fiction was Harold Grutzmacher. Everyone said he was leaving Knox at the end of the 1964-65 school year, and his second semester fiction workshop would be the last opportunity to have a class with him.

"Grutz" was young, glib, charming and somewhat glamorous. Seldom without a lit cigarette, he exuded the writerly blend of sardonic wit and surprising gentleness. At some point towards the end of first semester I ambushed him outside Old Main and asked to be in his upcoming class. He refused at first--it was oversubscribed already. We were interrupted but I stuck around and finally he relented a bit, and told me to drop off a story I'd written, and we'd see.

I may have actually written a story for this purpose, but in any case I provided ten pages of fiction that must have shown enough promise for him to accept me in the workshop.

Looking at that manuscript now, it does have some surprisingly apt turns of phrase and, for a story in which nothing much actually happens, a narrative flow. I recall that he picked out a single detail he liked: the protagonist reads a letter he's just received, and notices the point at which the handwriting switches from black ink to blue.

My emphasis on physical detail came in part from Cassill's instruction, as well as a bit from the example of John Updike's stories. But mostly it came from J.D. Salinger, who--especially in his stories--was the poet of clothes and postures, and where cigarettes and ash trays were placed. In Salinger, that description was more than description; it was substance, and it was style. The switching from black to blue ink was a Salinger-like move (though not literally a steal.)

Moreover, so was the letter. In the story it functioned as offering a different point of view, a clarifying judgment, on the protagonist's self-absorption. But the fact of it and the tone of it came from the big brother letters and phone calls in Salinger's Glass family stories and novels, or even the Hollywood big brother D.B. in Catcher in the Rye. I'd recently been missing a big brother's point of view (hard to get when you're the oldest and the only boy.) In my senior year of high school I'd actually invented a big brother for myself in letters to a young woman in nursing school who'd graduated the previous year, as a kind of running joke, and so I would have someone more interesting than me to write about.

The only surviving manuscript or fragment I'm sure was for this course is a memorable one for me: it is my first story analyzed for an hour by other students in the workshop class, presided over by Mr. Grutzmacher. In fact, it is the very copy, because it contains my marginal notes on what they said about it. (There are a lot of them on the first page, but they grow sparser--not because there were fewer comments and criticisms, but because there were too many.)

Titled "A Little Less Than the Angels," it was an account of a walk along a wooded fringe of a golf course, taken by two Catholic high school students the summer before college, Ted and Jeanne. In Ted's pocket is a letter he'd just received from another student they both knew, Lois. She and Ted had something like a romance that seemed to die out before being unexpectedly revived just a few months before. In between, he'd been dating Jeanne. So he couldn't tell her about the letter.

Near the end of the story the letter is excerpted: Lois tells him she had to make a choice, between him and God. Her choice was to enter a convent. Summed up like this it seems funny if not cringeworthy, and perhaps the chief accomplishment of the story is that it does not seem so in its context. It's a crisis for Ted, which among other things, affects his relationship with Jeanne. That part of the story is largely true, compressed in time.

I noted in the margins several times the class critique that the shifts from "realism to romanticism" were confusing. Also "shifts in point of view," a regular criticism of student stories. Certain passages were rightly flagged for being trite in expression.

But the class also discovered possibilities I hadn't seen, or consciously intended. Ted keeps interrupting the conversation with Jeanne by claiming to see a light in the fir trees that she always just missed seeing. To me, this was just his way of distracting her from places in the conversation he didn't want to go, or just out of boredom with their mundane talk and life. But others linked it to the larger philosophical issues on Ted's mind, like destiny and faith. I wrote down one striking comment by an anonymous classmate: "Lois is never going to find God--but Ted will, in a pantheistic way."

There was a lot of discussion about the title and what it could mean beyond what was said--that all humans have some divinity, just a little less than the angels. I note that Mr. Moon thought Ted sees irony in this when he mentions the phrase, responding to Jeanne's observation of players in a sandlot football game they pass as "animals." (Was Mr. Moon at the workshop? Or did he read the story at another time?)

Grutzmacher commented that the story's principal faults were lack of proportion--Ted and Lois are strong, Jeanne is not--and the shifting point of view. Today I think the story's principal fault (apart from trite expressions) is that it is too long. Cleaned up and compressed and a third shorter, it might be a decent story. But that process was probably beyond my capabilities at the time. I wrote it so instinctively, and the feelings in it were being worked out on the page. I had no real distance.

After this workshop session, I took a real walk with Judy Dugan, who'd become a friend as well as sometime debate partner. As we re-entered campus, Mr. Grutzmacher saw us and smiled his approval. It's good to get some consolation after a workshop session, he said, for they can be brutal.

Now these many years--and many workshop and writing courses later--I have mixed feelings about writing classes and workshops, and doubts about the nature of their value. (This is no reflection on Grutzmacher, who remains a pleasant memory.) In any event, these days they've become more assembly-line and credentialing for my tastes.

The right teacher at the right time can be crucial to a writer's development and success. But whatever there is to learn from teachers and workshops, the primary lessons for how to write come from reading. Absorption, imitation and variation have always been the basis for learning any craft or art, but you don't learn much from watching somebody write (except maybe tenacity.) You learn from reading what they wrote. It doesn't surprise me that until very recently, no Nobel Prize winning writer had ever taken a writing workshop.

Like its immediate predecessor, "A Little Less Than The Angels" shows me a continuing J.D. Salinger influence, particularly in the dialogue. (Not in the letter--it's almost exactly from the real one.) Even the name Ted was probably suggested by Salinger's story "Teddy." (Or by Ted next door in Anderson House.)

Jeanne's one-dimensional character was in sympathy with Salinger's characteristic over-sensitive male among carefully mundane females, who are still intrigued and attracted. Salinger also dealt with questions of faith and value, even in religious terms, which was a vocabulary familiar to me from Catholic schools. Salinger's main characters gravitated towards mystical traditions, towards Eastern philosophy and Stoicism, all of which were more appealing alternatives. But this would be my last story in which these issues were overt concerns--except destiny. That keeps coming up.

In his exit interview in the Knox Student, Grutzmacher did not dispute this--his salary would be doubled, with additional benefits. But his job would also offer a fresh challenge--administering other teachers in the freshman writing program as well as teaching.

He also noted the uncertainty of the writing program's future at Knox, and the college's commitment to it. Indeed, he would not be replaced with a full time faculty member until my senior year.

At that point he'd published one book of poetry, titled A Giant of My World (which referred to his young son, Stephen.) I bought a copy at the Knox Bookstore, and he autographed it for me "with pleasant memories of a hectic year." I still have it.

Harold Grutzmacher went on to chair the Parsons College English Department, and after an administrative stint at the University of Tampa, returned to the Midwest to become Dean of Students at his alma mater, Beloit College in Wisconsin, another Midwest Conference school along with Knox.

There he was "Hal" and became "an influential member of the Door County community." In addition to his administrative work, his book reviews and columns, and eventually owning a bookstore, he wrote more poetry. His second book was a collaboration with his son Stephen, to whom his first book was dedicated.

He continued to teach writing at several schools in Wisconsin, even teaching freshman writing as a Dean. He helped several writers edit their books. There is still a series of annual awards in writing and other arts in Door County, known collectively as the Hal Prize.

Harold Grutzmacher died in 1998. A story about him, along with one of his poems, is here.

There's a corollary to my theory about the college experience--that all of history is experienced Now. The problems sometimes come when something seems Now but isn't. For example, in college we read Hemingway and Fitzgerald, and read about their milieu (Paris as a paradise of the arts, their dedicated editor Maxwell Perkins, etc.) It all seemed very Now, but most of it was long past, as some of us eventually learned the hard way. This was a more general problem in that the literature we studied stopped years before, mostly years before we were born. There were similar situations in other fields.

When it came to literature and related arts, the Knox counteractive to this absence of the contemporary was Sam Moon and the living writers and other active artists he enticed to campus. My first remembered experience of this was during that second semester spring. Every year a writer was brought in to judge student writing competitions, and for several days of talks and readings. That year it was the poet Robert Creeley.

Creeley as a writer and a presence electrified a good portion of the Knox student body--certainly all the writers. He seemed to change everything overnight. His late April reading in the Common Room was the first of several memorable moments I experienced there (and it was memoralized by a photo of Creeley taken by Knox student photographer Jim Bronson, which graced the back cover of a Creeley book published later.)

Creeley read poems from his collection For Love: Poems 1950-1960. It was the way he read them that mesmerized, and remains memorable. Reading certain lines in the title poem today, I hear Creeley's voice saying the words before I read them.

This in a sense was not a coincidence. Creeley talked about his poetics, based on William Carlos Williams and especially Charles Olson, with whom he'd worked at the fabled Black Mountain College. We got a mimeographed handout of Olson's Statement on Poetics (which he developed as a result of correspondence with Creeley), emphasizing the poet's breath as fundamental to the form of the poem. So Creeley's reading was a key to the form of his poems, with their short, tremulous, fragmented lines. (In marked contrast to Olson's own full-throated, arm-waving, histrionic style, as preserved in this video.)

Creeley also said that "form is never more than an extension of content." Olson wrote of "field composition" in which the poet "can go by no track other than the one the poem under hand declares..." He also referred to poems as energy discharges, and it was that tremulous energy, trying desperately to find expression, that gave Creeley's reading such presence and drama.

Looking back, I see that I hadn't had a real literature course yet, so in a sense these discussions on contemporary poetics was the first such instance in my college education.

Every student involved in writing or reading contemporary poetry was reading For Love that spring, and the following year's issues of the literary magazine (then called the Siwasher) showed Creeley's continuing influence on Knox poets. That possibly also derived from Creeley as the romantic figure of a contemporary poet: lean, dark-haired, with one eye missing, he looked like he'd stepped out of a western movie (rather than Harvard, where he'd been an undergrad.) His voice belied his New England background for those with a more experienced ear than most of us, and there was a certain rugged Puritan rigor (and guilt) in his writing and persona, if not necessarily in his behavior.

My copy of For Love has several poems marked, and a note on the page with the poem "After Lorca" which indicates that Creeley said the lines really were Lorca's, but no Lorca scholar could locate them. But it would be a few years later, though still before I left Knox, that I settled on the poem in it that still means a great deal to me. I felt then and now that it's somehow emblematic, though of what I can't quite explain. It's called "The Innocence:"

Looking to the sea, it is a line

of unbroken mountains.

It is the sky.

It is the ground. There

we live, on it.

It is a mist

now tangent to another

quiet. Here the leaves

come, there

is the rock in evidence

or evidence.

What I come to do

is partial, partially kept.

|

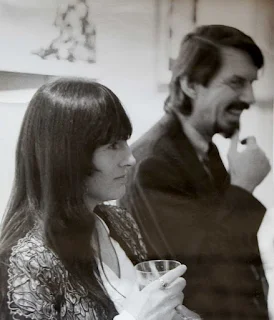

| Bobbie and Robert Creeley |

Many things happened in those months, but one of them was spending time with Robert Creeley, on the teaching staff there. I remember in particular a party at which Bob was holding court at one end of the house, and his wife Bobbie at the other end. Bobbie read palms, and she loved the maze of lines in mine.

Creeley was instrumental in getting me admitted to the graduate writing program for the following year. He felt that the small college was no longer adequate preparation for the literary life, and that something more urban like Buffalo would help. Eventually I decided not to stick around. The last time I saw him was a year or two later at a reading at Boston College, and I spoke briefly with him afterwards, essentially to let him know that I was there in the Boston area, and doing okay.

I have another 8 or so of Creeley's books: poems, interviews and essays, short stories, his only novel. One of the poetry collections, Pieces, was an unexpected best seller due to being sent to American troops, though he was a vocal opponent of the Vietnam War. Creeley thought it was a mistake--somebody thought it was about guns, he surmised, or "pieces." It's one of his best anyway.

As fragile and self-subverting as he sometimes seemed, Creeley had a long career, publishing some 60 books and becoming an eminent and award-winning poet and teacher. He helped a lot of young writers along the way. He died in 2005--forty years after that April week in Galesburg.

Next time: Philosophy, Fred Newman and the exodus of dreams, as the second semester 1965 concludes.