Somewhere nearby President Kennedy was also watching the parade. He'd just been sworn in as President, and was about 44 hours away from another milestone (which was shaking my hand.) But President Kennedy saw something in that parade that I didn't. Moreover, he did something about it, and it changed history.

|

| Robert Kennedy is in one of those cars. My photo mostly shows the job done clearing Constitution Av. of snow that had piled up from a storm the days before. |

Back at the White House, he asked why. Eventually he was told that there was only one black officer in the entire Coast Guard. Again, he asked why. It turned out to have something to do with Academy requirements. Eventually he got those requirements changed. From today's perspective, we can see that it was in a real way a seed of Affirmative Action.

|

| Washington Post front page 1/21/1961 |

a reputation it maintains to this day.

Towards the end of his address, after speaking about the major goals and policies of his upcoming administration, Kennedy cautioned: "All this will not be finished in the first 100 days. Nor will it be finished in the first 1,000 days, nor in the life of this Administration, nor perhaps even in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin."

The "let us begin"--three short words, four syllables--he separately emphasized, pounding out the rhythm on the lectern. References to the future now are prophetic and tragic. But the words of action--that emphatic burst of intent--remain inspiring.

And they were true. For reading this chapter now, I see how many beginnings there were: how many seeds were planted that did not fully bear fruit for years or even decades, but eventually changed things. JFK and RFK often talked about "the unfinished business of this country," and of course that business remains unfinished. But there was progress, and it was seeded, or began or was accelerated in the Kennedy administration.which began that day, January 20,1961 and ended on November 22, 1963.

Kennedy fought a tough primary in West Virginia and spent a lot of time in the state. It was perhaps his first close-up view of poverty--including white poverty-- particularly in rural areas of Appalachia that rivaled anything seen in the Great Depression. Perhaps this was behind his first executive order as President: to increase the quantity and quality of surplus food available to low income Americans.

The federal government distributing "surplus food" had been its main way of addressing hunger since the Great Depression. Being on welfare was not required--families below a certain income could go to distribution centers and get everything from powdered milk and eggs to cheese and canned meats (including Spam.) At a particularly lean time for my family in the 1950s, big blocks of surplus cheese and tins of roast beef (which tasted more of the tin than the beef) began showing up in our household.

Also in those first 100 days, Kennedy ordered a pilot food stamp program, so that eligible citizens could get the same food as everyone else at the supermarket, including fresh produce. That became a full-fledged program in the Johnson administration, and food stamps replaced surplus food in the 1970s except as a supplementary program for targeted populations, such as Indian reservations.

Much of what Kennedy set in motion immediately was designed to take up the slack in the economy and "get America moving again," as he'd promised in the campaign. But he made crucial changes within the government that seeded more changes to come. His appointees made entire departments--from Defense to the Post Office--more professional and accountable. He changed the composition of the Business Advisory Council within the Commerce Department from a self-appointment gang of cronies who used it to enrich themselves to a group selected by the Secretary of Commerce, with their meetings open to the press. Greater transparency was coming to government. At the same time, a more active Labor Department was looking out for workers but also entering labor disputes as arbiter.

Some of the most eye-opening changes concern the US military. The defense budget had become a disorganized grab-bag decided on by the various services in conjunction with big arms contractors. Kennedy ordered a complete review of US defense capabilities and needs, and after hearing from the military services and congressional leaders, created a defense budget that aligned with the findings of this review, and choices to upgrade and make defense more flexible.

This was a specific result of a more general policy of great importance. Kennedy, this chapter asserts, "inherited a government in which high-ranking military officers had grown used to issuing pronouncements on diplomatic and security policies, however embarrassing to their civilian superiors. President Kennedy lost no time in reasserting the Constitutional principle of civic supremacy."

This was a battle that would extend throughout his presidency. Deferring to the military caused the Bay of Pigs debacle, while defying top military leaders essentially saved the world from thermonuclear war in the Cuban Missile Crisis. But when the novel Seven Days in May, which depicted an attempted military coup in contemporary America was published in 1962, Kennedy told friends it was a plausible scenario. Today civilian control of a more professional military is established.

Kennedy sent a stream of legislation to Congress, on everything from housing to national parks and scientific research. Some of it notably was to continue or finish projects begun in the Eisenhower administration, including the federal highway program. But much of it was innovative, and among these bills were several seeds for the future, notably the legislation on the issue then called "medical care for the aged," to be administered through Social Security. Republicans opposed it as "socialized medicine" (much as they opposed Kennedy's call for a raise in the minimum wage to a grand $1.25 an hour, which they said would ruin the economy.) Eventually "medical care for the aged" would result in what we know as Medicare.

In 1961 ecology was a future word and the environment was not yet a thing, but thanks mostly to his pioneering Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall, Kennedy sent a special message to Congress about coordinated federal responses and policies to control air and water pollution, conservation of forests and water, and preservation of public lands. These were the seeds of environmental action.

|

| Early class of Peace Corps volunteers |

In Civil Rights, Kennedy instituted reforms that would ultimately result in the federal government leading the country towards equal opportunity and diversity in the workplace.

After the specific efforts to encourage racial diversity in the Coast Guard, the Kennedy administration took a number of meaningful steps in the civil rights area, including the Kennedy Justice Department entering several desegregation cases on the side of African American litigants. But in terms of the future, Kennedy's major step in the first 100 days was to ban discrimination in federal government employment, as well as the contractors it hired. This covered nearly a quarter of the national workforce.

But he did more to make the order effective. He ordered a report "which would provide for the first time a statistical breakdown by color by all those whose work entailed the use of federal funds," as well as recommendations on how to remove inequities. He created an executive structure to receive this report and to use it to end those inequities.

But even planting the seeds was not over in the first 100 days in the brief life of this Administration. Some of the better known seeds were planted very close to the end. The Limited Test Ban Treaty not only seeded the many arms reduction and anti-proliferation treaties entered into by the US, Russia and many other countries, it changed the dynamic of the Cold War. Lines of communication and trust based on common interests and respect were, for one thing, suddenly crucial when the Soviet Union fell apart and nightmares of scattering bombs, or a collection of small and barely formed nations all with nuclear weapons, were avoided.

Kennedy breathed new life into the treaty negotiations with his historic address in June 1963, often considered his best speech after his Inaugural. (The basic themes were sounded in fact in that Inaugural.) The treaty proved unexpectedly popular, and Kennedy milked public support and also called in some crucial favors to see it ratified in the US Senate, which was in some ways more difficult than getting the USSR to sign it.

Then the evening after that landmark speech, he made another one--a television address, scheduled at the last minute, in which he announced his Civil Rights bill, the most sweeping in history. He would not live to see it passed, but eventually two bills including the Voting Rights Act would become law.

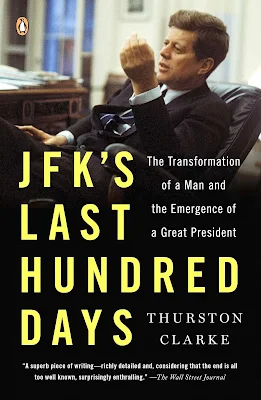

The seeds continued to be sown until the end. Thurston Clarke's 2013 counterpart book, JFK's Last Hundred Days, uses facts gathered during decades of historical research and reportage to flesh out and at times reveal some of the dramatic accomplishments of Kennedy's last months, which included securing the Test Ban Treaty ratification.

Clarke makes a convincing case that JFK's horror of war and suspicion of military brass that began with his experiences in World War II, were paramount. Some of the most prominent military leaders were pressuring him to launch a preemptive nuclear strike against the Soviet Union in late 1963, when US missile superiority was at its height. The Test Ban Treaty was even more crucial because of this pressure.

Still, the forces within the government opposing him, particular on military matters and policy regarding the Soviets, were known to simply not carry out his orders. This included the failure to send the response that Kennedy wrote to the Soviet premier's friendly letter, and disregarding his order to close obsolete missile bases in Turkey that later became a point of conflict during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

|

| March on Washington leaders with JFK immediately afterwards |

There were smaller seeds sown as well in these last months. He had ordered a report on how equality in hiring for women in the federal government and the private sector could be encouraged, and he spoke at the presentation of the report, despite being (in Clarke's terms) a male chauvinist through and through.

He also took affirmative action of another sort by appointing the first Italian American and the first Polish American to the cabinet. He was criticized for doing so as base politics, not taking into account "Kennedy's determination to make it easier for other ethnic groups to walk through the door that his election had kicked open," as Clarke writes. For Kennedy was the first Catholic to be President, and the first Irish American.

Clarke noted that these appointments of individuals from immigrant groups of a few generations past came at the same time as Kennedy (who'd authored a short book called A Nation of Immigrants and had sponsored bills expanding immigration as a Senator) had submitted to Congress an immigration bill that summer that promised "the most radical transformation of U.S. immigration laws in almost half a century."

Kennedy had argued for the end of discriminatory national quotas. An immigration bill passed in 1965 (with the support of Senator Ted Kennedy), that came significantly close to this goal, and effectively dumped the discrimination in favor of northern European immigrants that had been US policy since 1920. Apart from issues of illegal immigration, this provision alone added to the diversity of immigrants and the country ever since.