The U.S. was withdrawing troops and negotiating, Nixon said, but the North Vietnamese were increasing their attacks. Action was necessary to protect American troops, and to avoid American "humiliation" and "defeat." "If, when the chips are down, the world’s most powerful nation, the United States of America, acts like a pitiful, helpless giant, the forces of totalitarianism and anarchy will threaten free nations and free institutions throughout the world."

Reading this speech fifty years later, it might seem eminently reasonable--except that by that time, few believed anything that the administration said about Vietnam, and with ample justification. Most of the assertions in the speech have proven to be lies. That phrase--pitiful, helpless giant--would become an epitaph of the era.

Instead, what jumped out of the TV screen was another escalation, this time an invasion of another country without either its formal request or a declaration of war. It was also a time of hyperbole, but it isn't much of an overstatement that, almost at the moment the speech ended, America exploded. In particular, its college and university campuses. Hundreds of them erupted in protest and in varying degrees of violence.

At Kent State in Ohio, that violence on campus brought the war home when National Guard troops fired on unarmed students and killed four. This instantly led to even greater and more widespread campus consternation. Within days, the normal functioning of higher education had pretty much stopped.

Eventually this disruption hit the isolated campus of Knox College in Illinois, with a certain surprise--when Time Magazine covered it, the article concluded that if it could happen in Galesburg, it could happen anywhere. And much to my own surprise, I found myself at the center of it, fifty years ago this week.

This historical moment was the product of many currents, pulled into the same whirlpool by the issue and situation of the Vietnam War in 1970. These currents can be represented by the phenomenon and the individuals involved in what was first called the Chicago 8. The Nixon Justice Department brought charges against eight participants in demonstrations outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968 (which I've written about here.) Ironically, they used a provision of the Civil Rights Act meant to prosecute rioters in federal court when states refused to bring charges.

These eight individuals were also charged with conspiracy, despite the fact that several didn't know each other. They instead represented a continuum of protest, both in Chicago and (just as pointedly) in the years of the 1960s.

Tom Hayden was the most prominent of those who started in the student movement. While in college he was a cofounder of Students for a Democratic Society and the principal author of the Port Huron Statement in 1962, that applied the ideals of "participatory democracy" to all aspects of American society.

More broadly, the student movement symbolized political activism applied to internal college and university issues as well as issues that went beyond the campus. Hayden began in the Civil Rights movement in the early 60s, and became an antiwar activist during Vietnam. He always brought American-born ideals to these issues, as when he adopted the words of Sitting Bull for the title of his 1972 book on Vietnam, The Love of Possession Is a Disease With Them.

Then 1968 was a year of global student protests, notably in Paris (where student Daniel Cohn-Bendit became prominent) as well as the United States. The US protest that got the most attention was at Columbia University, where students occupied administrative offices and other buildings, and were forcibly removed by New York police.

There were a bewildering array of theories, beliefs and political positions represented in student activism, with adherents quoting everyone from Lenin and Mao to the more fashionable intellectuals such as Marcuse. The doctrinaire were not the majority however. Students with a wide range of orientations and backgrounds came together on broader issues such as the war or issues specific to their college or university--or, as would be happening more intensely, in self-defense.

Several of the Chicago 8 were organizers with roots in earlier traditions, such as unionism. David Dellinger was the oldest defendant at 54, a pacifist and Civil Rights activist. But just as SDS had broken into factions, at least one of them advocating violent resistance, there were also stark divisions in the Civil Rights movement, especially since the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Defendant Bobby Seale was a co-founder of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, an organization also proposed with a document setting forth its ideals (and demands) in the Ten Point Platform. Though the document and many Black Panther Party activities stressed community service and self-determination, the imagery and rhetoric were often militant and violent, emphasizing armed resistance.

|

| The Chicago 7 |

So there was conflict and commonality, but it was the commonality that was most apparent to the older generations of conventional America, the Silent Majority (as Nixon called them). The Generation Gap was its strongest in these years, and it became clear (as in the Anthony Lukas reporting) that jurors were judging these defendants as much on their appearance and demeanor as their alleged actions. The common culture (or counterculture) was real enough, but the differences, especially in tactics, were also real, though that wasn't apparent to the most threatened outside this culture.

It is worth mentioning at this point the violence that members of all these groups were suffering, apart from those in Vietnam. Violence against activists opposing racism was no longer restricted to the South. Apart from the ordinary violence that African American men could expect, black activists were particular targets, and the Black Panthers most of all.

This was brought home to Knox College students when Fred Hampton, Illinois chairman of the Black Panthers, was ruthlessly gunned down in his bed and killed by Chicago police and FBI in December 1969. Hampton was engaged in organizing the multicultural Rainbow Coalition that brought together street gangs to work for social change instead of killing each other. Hampton had evidently visited Knox that year. When I read of his murder in an underground newspaper, his photo showed him wearing a Knox sweatshirt.

Another aspect was highlighted by Chicago author Richard Stern, who visited Hampton's apartment after his murder (and that of another man in the apartment), and noted the books that were there. In a brief essay that later became the title piece of his 1973 collection, he wrote:"...it meant that the blood which lumped the mattress and stained the floorboards was in part the blood of the books as well as their readers. If it didn't make that fierce nest a shrine, it lifted its meanness and anonymity."

But previously immune white youth were also victims of violence, and not all because of politics. In a Ramparts collection on the cultural revolution, several articles chronicled routine violence against "hippies" and members of communes--assaults, arson, rapes-- unrestricted by age or gender.

Students experienced beatings and routine tear-gas during political protests, and the campus was no longer a sanctuary. In response to this violence and to the endless war, some protesters engaged in violence against property. Some was planned, some spontaneous, some extraneous, and some undoubtedly fomented by government agents, agent provocateurs.

Violence against student activists was encouraged by the White House, in v.p. Agnew's rhetoric and Nixon's praise of the "hardhats" who attacked protesters. Even in his Cambodia speech, Nixon asserted: "We see mindless attacks on all the great institutions which have been created by free civilizations in the last 500 years. Even here in the United States, great universities are being systematically destroyed." There would be more of this after the speech, when the protests started.

The Chicago convention itself was a prime example of official violence, though the trial of demonstrators attempted to distract from this. The government's own Walker Commission concluded that it was the Chicago police that had rioted.

This long and highly theatrical Chicago trial was featured on the evening news all through the 1969-70 academic year. That theatre was at times inspired and hilarious (Hoffman and Rubin were said to have appeared in court one day wearing judicial robes. When ordered to take them off, they did so, only to reveal Chicago police uniforms underneath.)

But the theatre of this trial was more consistently horrifying and enraging. Right from the start, the judge refused Bobby Seale's request for his own lawyer, or to represent himself. When he continued to protest, the judge had him bound and gagged in chair in the courtroom. That image--seen only in the sketches permitted during court proceedings--became indelible. Bobby Seale was soon separated from this trial, and so the defendants became known through the history since as the Chicago 7.

The verdicts came down in February 1970. The trial was so manifestly unjust that the anger and alienation it engendered were still in the air in May. (Though some defendants were found guilty on riot charges and on contempt of court, eventually all the charges were thrown out because of the evident bias of Judge Julius Hoffman.)

When Nixon made his Cambodia speech at the end of April, I was in Buffalo, New York. I was visiting a friend from Knox, Steve Meyers, who was a graduate students in the State University of New York at Buffalo English department. I was applying for admission in the writing program.

At that moment the University was already embroiled in very serious internal conflict. Charges of specific instances of institutional racism and other issues, some of them related to the war, had led to demonstrations in early February, which led to arrests, which led to more demonstrations, which led to the University president calling for Buffalo police on campus, which led to even larger demonstrations, including a sit-in by 45 faculty members, who were arrested.

Soon the streets near campus became battlegrounds between police and presumably students, with barricades, tear gas and rock and (it being Buffalo in winter) ice-throwing. Steve and I listened to the campus radio station reports each evening, and read the student newspaper, the Spectrum.

We also attended a large meeting of students and faculty, perhaps just the English department, perhaps not. But one topic discussed was calling for the resignation of the university president. (Already several of his top administrators had decided to move on, and at least one high profile faculty member--Edgar Z. Friedenberg, author of The Vanishing Adolescent that had so impressed me in high school--resigned from the faculty.) I remember two things from this meeting: Leslie Fiedler's impassioned speech saying how grave it was to call for a president's resignation, and why he was doing so; and being warned by someone while we were waiting for the meeting to begin not to even chat about anything controversial because there were likely to be FBI or other government agents in the crowd. This proved to be generally accurate.

After spring break in mid March, the intensity was dying down, only to flare up suddenly in response to Nixon announcing the Cambodian invasion. Fighting in the streets between crowds and police resumed at a higher pitch over that weekend.

There were significant protests the next day--on Friday May 1--at Princeton, University of Maryland and other campuses and in cities like Seattle, as well as smaller protests at places like Kent State in Ohio.

Also on Friday, President Nixon spoke to Pentagon employees in a statement that made the front pages by Saturday, saying "You see these bums, you know, blowing up the campuses...I mean, storming around about this issue, I mean you name it get rid of the war, there'll be another one."

On Sunday, a meeting of representatives of 11 universities met at Columbia U. and issued a call for a nationwide student strike the next week, declaring that “classroom education becomes a hollow, meaningless exercise,” in the face of this escalation of war. Over the weekend, a protest march through Kent resulted in some broken windows, while on campus a small group set fire to the old wood frame house devoted to ROTC. It burned to the ground. The Governor of Ohio, whose own rhetoric had become even more heated than Nixon's, sent the National Guard to occupy the Kent State campus. National Guard were also called to the campuses of Ohio State, the University of Maryland and probably elsewhere.

The National Guard presence at Kent State stirred the campus. On Sunday, a 19 year old student named Allison Krause placed a flower in the gun barrel of a National Guard soldier, who may well have been 19 as well.

There was no strike at Kent State on Monday, so at noon, some students were going to classes, others to lunch. A crowd had gathered at the Commons--some to protest the Guard's presence, some for a previously scheduled protest that had been called off. The Guard ordered them to disperse but many did not. According to witnesses, the two sides were so far apart that the rocks students threw landed in the same open area as the tear gas the Guard lobbed.

On Tuesday, an Extra edition of the Spectrum headlined the call for a national strike, with an early report on the Kent State killings. By Wednesday it was a front page story, with that iconic photo, under the banner headline: "They shoot students, don't they?"

Maybe it was some homing instinct at a time of crisis, but Steve and I got into his MG and headed for Galesburg.

|

| Me and Steve Meyers, a snap from classmate Howard Partner, probably 1967 or 8 at Knox |

Somewhere I also saw a story quoting Kent townspeople who blamed the students for the shootings, with one woman complaining that the newspapers were printing the dead students' high school photos but they didn't look like that when they were shot.

Newspapers also reported that on Friday May 8, 200 construction workers attacked protesters in lower Manhattan, in what became known as the Hard Hat Riot. It lasted two hours, spilled into City Hall and left 70 injured.

Around this time, 58% of respondents in a Gallup poll blamed the Kent State students for their own deaths. Another survey (according to historian Katherine Scott) found that 76% did not support the Constitutional right to assemble and dissent from government policies. Whatever their accuracy, these polls reflect the atmosphere I remember.

|

| John Podesta |

John Podesta went on to other things, such as White House Chief of Staff to President Clinton, White House advisor to President Obama and campaign chair for presidential candidate Hillary Clinton. That--and his continued alumni support for Knox--probably contribute to his place in the College's official history of the Knox events of May 1970. At the time, the takeover of a dean's office was hardly something that earned a lot of praise from the college administration. In fact, it was scheduled to earn me jail time. But in retrospect apparently it has become an heroic deed, and Podesta is credited as its leader. We actually joked about this over dinner at his house in Washington, when he was between Presidents. John certainly was intimately involved in the events I am about to recall. But I'll leave descriptions of his role to his own memoirs.

Instead I will patch together my recollections with a few artifacts that have survived from that time, along with fragmentary notes I made at various times in the following few years.

Some 400 campuses went on strike that week, the first national student strike in US history. Knox College was not one of them. Some of its students were upset by this. I found there the same emotions as on other campuses--anger and sadness, frustration and disbelief, feelings of being betrayed and misunderstood, scapegoated and even hated.

Some months later I summarized what I observed. The activist students "were small in number, somewhat paranoid about their alienation from the majority of [Knox] students, factionalized and not all overly fond of each other, yet energized by the solidarity they saw [elsewhere] and the frustration they felt that their own campus was so unresponsive."

I described the situation as "volatile," and I recall some specifics of that. At one end of the spectrum were those students who wanted to work within established channels and the usual means of petitions, letters and demonstrations. At the other there was a small number of students angry enough to advocate violence, specifically setting fires and exploding bombs. And many, probably most, somewhere between them.

Bombing buildings was certainly happening on and around some campuses, and there were individuals and organizations that advocated violence. These particular students at Knox did not strike me as radical ideologues. Mostly they were angry young males. Some of them actually did make a bomb which they attempted to detonate. It may have simply been a stink bomb, I'm not sure, because it didn't work. But it was enough to be alarming. I was frankly less worried that they would blow something up than I was that they would blow themselves up. They seemed more impulsively angry than doctrinaire, or competent at bomb-making.

I recall several meetings held in a large, mostly empty room at the off-campus apartment shared by Carol Hartman and Mary Maddox, where I was staying. Eventually these meetings coalesced around finding a plan of action that everyone could support. I saw that it had to be peaceful but forceful, or at least dramatic.

|

While I was at Knox that spring I was reading Jerry Rubin's book, Do It! I'd previously read Abbie Hoffman's books, Revolution for the Hell of It and Woodstock Nation.

I'd been at the big Pentagon demonstration in 1968 that had been in part a Yippie action, described in Rubin's book. I didn't subscribe to all their ideas but I did feel a certain vibe in common. Writer Jack Newfield called Hoffman "a pure Marxist-Lennonist: Harpo Marx and John Lennon." That worked for me.

Hoffman and Rubin's humor was natural to them but also tactical and strategic. They used humor and outrageousness as political jujitsu, to throw their establishment opponents off balance. The people who held the power--in government, the military, business and in colleges--couldn't be defeated or even meaningfully confronted on their own terms: in terms of power. But in other ways they could be.

Hoffman and Rubin used humor in part the way Madison Avenue did, to attract attention and to make their point through imagery and irony. They used other kinds of theatrics for the same reason, a kind of forerunner of live "memes." But they also used humor as a weapon, as psychological leverage. With humor they could expose hypocrisy, pretension and the truth behind these facades. It opened the opponent to ridicule they brought on themselves. There was also something disarming and winning about humor, especially irony. It made violence against those who employed it perhaps less likely, and certainly less justifiable.

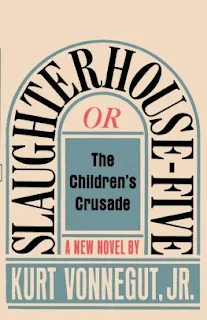

But in this context, humor was also revelatory. By this time, Kurt Vonnegut's novel Slaughterhouse Five had made him a ubiquitous name on campuses in particular. That novel joined Heller's Catch-22 as cultural--countercultural-- touchstones. Both novels employed what was sometimes described as black humor, but which novelist Vance Bourjaily insisted was more accurately called gallows humor. In this context it conveyed Mark Twain's view (Twain being one of Vonnegut's models in particular), that "the source of Humor itself is not joy but sorrow.” It was a way to work with the pain to get at some sort of meaning.

The Yippie approach also had the advantage of appealing to almost everyone in that room as a common action, though I'm sure many had their different reservations. However, many were Yippies at heart anyway. So we proceeded along that line. Was it the best approach to take? Maybe not. With a more straightforward approach, there may have been more support among students, faculty and even administrators than anyone in that room believed there would be. But I don't regret the choice. Because in the end there were no bombs. There was no violence.

This being Knox, everyone at the preliminary meetings knew each other. Black students had organized several years before and a representative attended at least one of the meetings, but the black students decided not to officially participate in a common action, and keep control of their own message.

At the final meeting the target and the time were decided, and the small group of students who would enter first. I believe there was even lighthearted discussion of style--what kind of outrageous costumes we would wear. But apart from a couple of opening statements, nothing much was planned. Most of these actions elsewhere were largely improvised. But this one was continually improvised by design. It was part of the point.

Just about all I knew of what to expect came from reports from other campuses, and books such as The Strawberry Statement by James Simon Kunen, about the Columbia takeovers. Again, I saw that Kunen took a light, personal approach. The cover of his book featured an effusive endorsement from Kurt Vonnegut. So that book as well as the Yippie books were in the back of my mind.

At around 4 on Friday afternoon, May 15, a handful of students entered Dean Sanville's office and handed him the Eviction Notice, which began: "In the name of Abraham Lincoln, Bobby Seale, Bobby Dylan and the scholars of Woodstock Nation at Knox College, the current administration is hereby evicted from Old Main."

It ended by declaring solidarity with the national and international fight to "free Asia from imperialist oppression, to free the nation from racism and repression, to free the planet from self-destruction, to free ourselves." It was signed: The Students Are Revolting.

That's the name I came up with: a Yippie pun. In subsequent documents, it was shortened to the acronym SAR, but it took Time Magazine to point out that the true acronym was TSAR, which was even better because it was funnier and in the same spirit of mirroring expectations and throwing them back. Happy accidents will happen.

My notes remind me however that the phrase had a Knox precedent. I remembered it from a Mortarboard satirical skit--the last one before they were temporarily banned for being salacious. "The students are revolting" was a line said, with appropriate emphasis, by the Dean of Students.

The students in that first group reported that the Dean and his secretary seemed unsurprised by the takeover and left without argument. (They got maybe an extra hour start on their weekend.) After the first group took possession, reinforcements of around 30 arrived. We locked the doors and opened the first floor window, so that people could enter and exit as Lincoln did when he "went through Knox College" and into Old Main. (Though not, scholars suggest, by that same window.)

In the office we found the previous night's campus "activity report" which stated: "God provided us rain" Everything quiet on the campus. We also found college president Sharvey Umbeck's memo on how to deal with crisis situations. Though it included some surprising humility (" Don't focus on finding a scapegoat...We start by searching our own souls before seeking fault in others") the basic message was to emphasize the positive and "develop a program which turns the crisis to the College's advantage."

We issued a press release: From an original strike force of 2,000 who nonviolently took over the administration, the ranks have grown to nearly a million...We are getting all our orders from Ho Chi Minh. Then everyone was encouraged to issue their own press releases, which they did, on the best available official stationery. Dean of Students Ivan Harlan stuck his head in, saw us using the phones, and left to have the phones cut off.

I later described the occupation as an open-form action without imposed structure, an expression that became a challenge.

"We're not being violent. We are having a political party," that first release said. By evening this was literally true. Somehow a rock band appeared (again, not previously planned), and set up in the Old Main hallway. Soon there were hundreds of people outside and inside--talking, arguing, and occasionally dancing. They were students, faculty, the occasional administrator, and the college public relations person.

|

| Photo from the college archives, taken in Old Main that night. That's Robin Metz in the foreground, and that's me in the funny hat behind him. This is the only photo of the event I have. |

Some of the students who originally threatened bombing were particularly upset by the party atmosphere. By that time news had spread of more students being shot by police, this time at the predominantly black college, Jackson State in Mississippi. Two were killed and 12 wounded. So the rest of us responded by pulling the plug on the band and asking people who wanted to discuss further action to stay, and others to leave.

When things quieted down there were (my notes indicate) now about 80 committed to the occupation. This larger group had a serious and heartfelt discussion that went on most of the night, interrupted for a time by drunken comments and personal insults from the other room (aimed at me, for one) by a few members of the faculty and administration. A meeting of a faculty committee, probably the Student Affairs Committee, was scheduled for 10:30 in the morning.

The discussion ranged from the war in Vietnam and now at home, to earnest talk about community, ideals and possibilities. This week that forcibly took everyone out of regular time was an opportunity. A consensus quickly arose (again, I'm referring to more or less contemporaneous notes) that the students who were now present wanted a strike, with official mourning for the Kent State and now Jackson State students, and discussions of relevant issues instead of standard classes. The difference of opinion was whether or not to bring such a proposal to the faculty committee. Some believed they would consider it, others doubted it. Almost everyone realized simply making the proposal was a concession, a return to the old power dynamic of asking for something.

Eventually everyone agreed to work out a proposal, and that's what happened the rest of the night. Unfortunately I don't have a copy of it. But I believe it proposed several days of a "free university" devoted to relevant issues. A group of representatives was elected, and they took it to the committee in the morning, while everybody else tried to get some sleep on the floors.

I remember one moment from that strange night. I was walking through a group of students sitting and lying on the floor, when one young woman looked up at me and smiled. I hadn't known her before, but she looked at me with such faith and trust. I felt a particular responsibility placed on me by that look, beyond what I'd felt from the start of this, and I knew at that moment that I would do my best to see that no harm would come to her or anyone, as a priority. We all knew that the police might well become involved at some point, for not even Knox College was immune.

On Saturday morning the faculty committee refused to discuss anything with occupation representatives while we occupied the offices, because (they said) that meant the faculty was under duress. So the representatives roused the sleeping occupier and we all went to the committee room down the hall. The faculty did not discuss their proposals but rejected their legitimacy, and harshly criticized the occupiers.

Cooler heads might have expected this, and even seen it as a part of the process that would end up in some sort of compromise. But (my notes more than indicate) most of the students were shocked by its dismissive intensity, involving what would today be called shaming. The desires and possibilities they had articulated, sometimes tearfully, in the suspended space of the night, were ignored and disdained.

A theorist might suggest that the Yippie/Dada occupation had monkeyed with the structure and mystique of authority, denying its moral validity, and the faculty now reflexively attempted to restore and enforce that authority and mystique. Or it simply was an angry reaction with rational justification, which felt like violence to the exhausted and vulnerable.

The faculty meeting did have its Yippie moments. I noted that John brought a flashlight to the meeting and pretended to flash messages to confederates outside. He and the other representatives requested donations for the Old Main One--a student who'd been arrested for trying to shoplift chains, to chain up the doors.

In any case the faculty response also seemed like part of a bad cop/good cop strategy, because when we got back from the meeting, the Dean of Students entered, made "a few subtle threats" but offered to negotiate. "I'll be in my office," he said. "We'll be in ours!" one of the students shouted, to cheers. The occupying group seemed on the verge of splintering until that moment.

The deans stuck around and talked with whoever came into their offices. Perhaps some actual negotiation began at this point, but it mostly became chaos. The deans' huddle was interrupted by a student asking for a match, and then leaving. Just as one of the more traditionally liberal members of the occupying group was explaining to the deans that one of these days things might get so bad that somebody might throw a bomb, in slid a long sputtering fuse attached to a loaf of bread. Then 30 of the occupiers got down on the Old Man hallway floor and crawled towards one of the offices crying, "Crumbs! Crumbs from the table! Please!"

The occupation continued throughout the day on Saturday. There seemed to be only two alternatives: to acknowledge defeat, or await the police. We talked about it. We could ask those not willing to be busted to leave, but the group believed it had achieved something by staying together, and they wanted to remain together. But to some, and especially to me, the whole group staying required trusting that the police would not be violent, and in this week that did not seem a safe bet.

And what would be gained? Injury or worse, radicalization of some, a lot of alienation and turmoil with lasting repercussions. This scenario had become predictable. Issues had been raised and a process begun, however disingenuously. It seemed time for a last act of Yippie jujitsu. The group made the final decision, with what seemed like relief.

In the darkness of very early Sunday morning we packed up and left, announcing that we were enacting the solution to the wearisome question of how do we get out of Vietnam? Our answer was: declare victory and go home.

Later I learned, probably from Becky Harlan, Dean Ivan Harlan's daughter, that a police raid had been in the works, working with the college. Students who participated would simply be sent home, but--as an ex-student Outside Agitator-- I would be arrested, as would the other ex-student present.

Shortly after the occupation, the college did call off classes and held an open university for a day or two. I can't imagine where they got the idea.

The occupation and my participation in it got me some odd responses. Some I thought would be more positive, weren't. But one faculty member I expected to be hostile--in fact the professor who'd flunked me and adamantly refused to let me graduate--complimented me on taking an interest in my old school, with a smile. To this day I don't know if he was sincere, or more skilled at blank sarcasm than I'd ever seen.

The head of college public relations--who I've decided not to name here-- may have felt personally betrayed because he'd employed me writing for the alumni magazine and tried to get me a summer reporting job while I was a student. In any case he was bitter, angry and very hostile. While it was going on, I'd written a verse parody about the occupation called, naturally enough, "The Students Are Revolting." The main character was Free Podesta, which wasn't meant to be John specifically, but was a pun referring both to the "Free Podesta" signs and to Abbie Hoffman's adopted name of Free, to designate a kind of Every-Protester. Later someone slipped me this p.r. man's own Shakespearian verse parody, quite skillfully written, with personal digs at a number of students but in which the chief villains are me ("King Owinski") and somebody called "Jan Siesta."

All of this reminds me of something Abbie Hoffman said years later:"We were reckless, we were headstrong, we were impatient, we were excessive. But goddammit we were right."

During the occupation I snuck out a few times, once to go to the library to check out the story about the occupation in Time Magazine (with its immortal quote, "If it can happen at Knox College, it can happen anywhere.") Oddly, there were a couple of alums I knew who visited Knox that weekend, for reasons of their own. One was Neil Gaston, one of the first of my classmates I met my first year. I ran into him in front of Seymour Hall. He was in the Army. He wanted to talk about books.

The other was Valjean McLenighan, in her Dress for Success period. We had a brief conversation before I had to go back. I only found her because Dean Deborah Wing saw me and said she was on campus and looking for me. In all my years at Knox I had hardly a good word to say for Dean Wing, and yet she was calmly civil with me. That was the last time I saw or heard from Neil. And though Valjean and I spoke on the phone, wrote letters and emails over the years, that was also the last time I saw her.

Two other relevant memories: I did participate in the open university, though my contribution was decidedly undistinguished. In retrospect it reminds me of the actor's nightmare, in which you find yourself on stage unprepared. I'd begun something which I'd planned as a multi-media presentation on "the classroom without walls," on old forms restricting new information and the revelations of disruptions, but I didn't have anything coherent in shape in time. And I was exhausted, so I mumbled and grumbled through the nightmare. All I managed to prepare, besides pages of preliminary verbiage, were copies of a page from a McLuhan book. The first sentence makes the point:"The speed of information movement in the global village means that every human action or event involves everybody in the village in the consequences of every event." That seemed true in May 1970. It's certainly true in May 2020.

But before I left campus I successfully made my first and only movie--a super 8 one-reeler, about 3 and a half minutes long, edited in the camera. It was about an Allison Krause figure. She also captured the imagination of many poets and others, probably for the flower in the gun barrel moment. I had immediately gravitated towards her also because she was from Pittsburgh, and grew up not far from where I did. I planned my scenes and shots but while I actually shot the film I had a tune in my head--Paul McCartney's first solo album was just out, and I kept hearing "Maybe I'm Amazed." The first and I think only time I ran the film, I put the record on, and the film and the song exactly matched, in length and rhythms. Spooky.

Two postscripts: Sometime in the 1980s I met Jerry Rubin. He was a millionaire by then, and was beginning to host networking parties. My literary agent at the time was helping him out. I rode in the back seat of a car with him, and attended one of his parties at his Upper East Side apartment. It was all carpeted in white. And I noticed that he served only white wine. I also noticed that I never saw him smile.

Also in the 1980s, when I was back in western Pennsylvania working on my mall book, I got an unusual phone call. Ivan Harlan and his new wife, the former Lynn Metz, were nearby and invited me to dinner. They were visiting St. Vincent College in Latrobe, evidently job-hunting. At one point Ivan told me that his daughter Becky had explained to him what my role was in organizing the occupation, that it had helped keep things from becoming violent. And he also told me that he missed those days. Students now were so boring.

No comments:

Post a Comment