“A man, to be greatly good, must imagine intensely and comprehensively; he must put himself in the place of another and of many others; the pains and pleasure of his species must become his own. The great instrument of moral good is the imagination;"

P.B. Shelley

"The soul without imagination is what an observatory would be without a telescope."

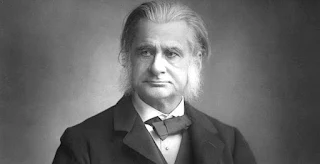

Henry Ward Beecher

When the forest fire approaches, most of the Morlocks run off in all directions. The Traveller is safe. Or is he? He sees several coming at him, and he "struck furiously at them with my bar, in a frenzy of fear, as they approached me, killing one and crippling several more."

But then, even in this frenzy of defending against an apparent onslaught, he realizes they are not really attacking him any more. They are blind, at least in the presence of the fire's light, and they are simply blundering towards him in their fearful frenzy to escape the light and heat.

And then the Traveller stops. "But when I had watched the gestures of one of them groping under the hawthorn against the red sky, and heard their moans, I was assured of their absolute helplessness and misery in the glare, and I struck no more of them."

In the physical details of this sentence, and in the words "moans" and "misery," the Morlocks are "humanized" to a new extent. But the Traveller also concludes that they are helpless. Killing them when they were attacking him, regardless of how good or bad it might feel, was justified and necessary self-defense. To kill them now, however good it feels or however angry he still is, would be murder.

John Huntington notes this sentence, this "I struck no more of them" and a later passage in which the Traveller is mourning the death of Weena and considers revenge ("a massacre of the helpless abominations") but "contains" himself, as key examples of how the Traveller's humanity is different from these species: he can exert self-control.

"It is his ability—a distinctly human ability—to bridge distinctions, to recognize an area of identity within a difference, that sets him apart,” Huntington observes. “The Time Traveller is able to assert an ethical view in the face of the evolutionary competition that rules the future."

The ethical view, beginning with an insight of empathy, that is the human difference. This was the position of Wells' teacher, T.H. Huxley, going back some 30 years but expressed most eloquently in his lecture “Evolution and Ethics,” his final and summary statement which was delivered and published while Wells was writing The Time Machine.

Huxley concedes that natural selection is mostly a brutal process, and that as animal life, the human species has been subject to it. But at this point in its evolution, humanity has developed both consciousness and civilization, which will be the basis of its particular "artificial" evolution.

Huxley didn't believe that evolution meant progress or guaranteed human triumph. Like other species, humanity would naturally peak and then decline, perhaps becoming extinct. But before the earth dies or some outside force suddenly overtakes or wipes out the human species, humanity can exercise a great deal of control over its fate. That will require some counter-force to natural decay, or new skills that will keep humanity going.

Technology is the obvious example of a new skill, except that technology without conscience and conscious control is the best candidate to be the instrument of humanity’s self-destruction.

Huxley believed that the counter-force would be human ethics. Humanity could change the rules of evolution by the ethical decisions to work for the betterment of all:

"The practice of that which is ethically best—what we call goodness or virtue," he wrote, "involves a course of conduct which in all respects, is opposed to that which leads to success in the cosmic struggle for existence. In place of ruthless self-assertion it demands self-restraint; in place of thrusting aside, or treading down, all competitors, it requires that the individual shall not merely respect, but shall help his fellows; its influence is directed, not so much to the survival of the fittest, as to the fitting of as many as possible to survive. It repudiates the gladiatorial theory of existence."

Both Huxley and Wells recognized the importance of cooperation and altruism in biological evolution. Huxley used examples of bees and ants, and Wells wrote in an 1892 essay (“Ancient Experiments in Co-Operation”) that the idea that competition alone causes changes in biological evolution is “a horrible conception, as false as it is evil.”

Some (including G.B. Shaw) would note that in certain circumstances, human self-restraint does enhance survival, and that human reason and ethics add to the fitness of individuals and the species, so they are actually features of human evolution, though perhaps not yet in a Darwinian timeframe. Intelligence, self-knowledge and ethical behavior are successful adaptations for the species.

Nevertheless, even without these assertions, ethics were important to Huxley because they define the human. That’s why it is important that humanity fosters “the survival of the ethically fittest.”

The ethics themselves define the human, but so does the intelligence and creativity to formulate them, the expression of freedom and the act of will to choose them.

So the meat-eating Time Traveller who exults as he strikes and kills, controls the expression of these responses and feelings, by using his ethical conscience. In this case, the situation doesn't require a lot of soul-searching and analysis, as it might in others. Not killing the helpless is recognizably an aspect of English "fair play," and the Traveller's quick decision, which he seems to feel will be obvious to the upper middle class Englishmen listening to his story, suggests that civilization can help to make ethical restraint nearly as reflexive as fight or flight.

Still, the pattern of thought is fairly sophisticated. He realizes that the violent emotion he is feeling towards the Morlocks is not necessarily the same emotion the Morlocks are feeling. He realizes that because he finds the Morlocks loathsome, hateful and threatening at that moment, they don't find him so—if only because they can't see him, and have other things on their minds. They are not a danger to him just because they are ugly and strange. They endanger him only when they attack him.

His decision not to wreak revenge later also seems dependent on this idea of the Morlocks as "helpless," though very soon they prove not to be completely so. Still, there are plenty of real cases, and many stories and feature films, in which violent revenge (or "payback") is a reflex that does not take the current helplessness of the original perpetrator into account at all.

In The Time Machine, Wells subtly undermines the use of science to justify selfishness and conflict. By dramatizing the way evolution works—not as inevitable progress, or progress based on Social Darwinist or racist principles—he shows that left to its own process, natural selection does not necessarily favor the survival of humanity as a conscious, intelligent species.

The science that led up to Darwin had a close relationship to the industrial era. The Darwinian process of natural selection itself, extended as a general rule, sees nature as a kind of machine.

But in Wells’ story humanity achieved the perfection of a machine by dividing, and ending itself. “I grieved to think how brief the dream of the human intellect had been,” the Traveller thought. “It had committed suicide.”

At first a divided society seemed to work out for everyone, he speculated, in harmony with its environment until it became “a perfect mechanism.” By becoming parts of this machine, the elite and the servile became their roles, their unchanging functions. Humanity created its perfection by apparently following the Social Darwinist and possibly racist lines, and separating the species.

It worked for awhile, the Traveller speculates. But they "had lacked one thing even for mechanical perfection—absolute permanency." The environment changed, and the two halves of humanity no longer had the intellectual versatility to cope, other than in the awful way the Morlocks and Eloi did. "There is no intelligence where there is no change and no need of change," the Traveller says.

That versatility is energized in part by humanity's struggle to persist in its environment, but also by the internal energy of differences within humanity that challenges the mind, quickens the heart and deepens the soul.

Intelligence in these terms includes imagination and empathy, which is the imaginative act of understanding the emotions of another—or the Other.

Taking into account the information the Traveller acquired through empathy helped guide his actions. It’s a very human thing to do.

“Empathy” was not yet a known word in English when The Time Machine was written—its first instance is early twentieth century, although it was based on a German word coined a half century earlier. It was first applied to understanding the emotion in works of art, or the aesthetic appreciation of people.

Another feature of the human response that the Traveller applies to this future world is the aesthetic response itself--the appreciation of beauty.

For example, as he rests among the Eloi after his battle with the Morlocks, he reflects on the beauty of the sunny morning, and on the beauty of the Eloi as they again laugh and play by the river.

The scene may remind us of others in which the Traveller sits and observes the beauty around him. Beauty was the first virtue of this future that he saw, and now it seems to be the last.

It was on the hill as he gazed at the stars, thinking with some awe about the sweep of cosmic time, that he realized what the Eloi's relationship to the Morlocks was. It was then he looked at "little Weena sleeping beside me, her face white and starlike under the stars." With this Wells makes an instant connection between the beauty of the cosmos and the beauty of this frail child-like creature.

Some critics and readers have found the presence of Weena to be cloying and embarrassing, if not faintly perverse. But the childlike quality of the Eloi is metaphorically apt, as well as producing a certain tug of sentiment. Children as a rule are beautiful. It is not only a physical attribute but resides in their affection, trust, curiosity and delight in the world. It is in their eyes.

Otherwise weak and helpless, it is their beauty and the effect it has on adults that makes it their chief survival mechanism. This beauty is common to children of all ethnicities, genders, classes.

As they grow a little older, children reach out to other children, regardless of any distinctions. They have to be taught to judge by skin color. Children naturally get angry and act aggressively, but generally they must be taught to hate.

While ugliness alone is not enough to justify violence, beauty alone is worth preserving. The Time Traveller's impulse to take the beautiful child back with him is an impulse to honor the only living form of value he finds in the future. And though he cannot take Weena, he accidentally takes with him two white flowers that she had placed in his pocket.

It is these flowers that the narrator—the witness to the Traveller's tale—holds onto, "to witness that even when mind and strength had gone, gratitude and a mutual tenderness still lived on in the heart of man."

But before the Traveller can return home, he must retrieve his time machine. There is one more battle to fight, and a series of brief but memorable glimpses into the farthest future.

To be continued...For prior posts in this series, click on the "Soul of the Future" label below.

Starting With Stoppard

-

Tom Stoppard died in November 2025. From his first success in the late

1960s--*Rosencrantz and Gildenstern Are Dead-*- to now, I followed his

career and...

3 weeks ago

No comments:

Post a Comment