Arthur Conan Doyle “The Adventure of Silver Blaze”

Critics have found models for Wells’ Time Traveller in a variety of fictional characters and real people, from Beowulf to Gulliver, Oedipus to Edison. Doubtless there are multiple sources, but there’s one never mentioned that I believe must be prominently included: Sherlock Holmes.

Conan Doyle had the first success, with his Sherlock Holmes stories. Wells read and admired them, and in 1894—a year in which he was completing The Time Machine—he recommended the Holmes stories as a model for writing about science:

“The fundamental principles of construction underlie such stories as Poe’s ‘Murders in the Rue Morgue’ or Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes series, are precisely those that should guide a scientific writer...First the problem, then the gradual piecing together of the solution.”

Conan Doyle called Holmes a “scientific detective.” Like Holmes, the Traveller employs the scientific method in making observations in this completely unknown world of the future, then forms a hypothesis, and makes further observations to test it.

The Traveller’s basic assumption about the future didn’t last very long: he saw the large buildings in the distance and the graceful and beautiful Eloi as evidence of the progress he expected from the future. Then he realized the Eloi were on the level of children.

|

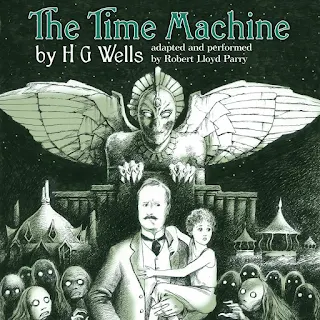

| This poster suggests the size of the Eloi as described in the text--Weena as child-size. |

The Traveller sat on the crest of a hill to watch the sunset and reflect on what he sees. The landscape is like a garden, with the palace-like buildings embedded in greenery. It was perfect. “The air was free of gnats, the earth from weeds or fungi; everywhere were fruits and sweet and delightful flowers... I saw mankind housed in splendid shelters, gloriously clothed, and yet I found them engaged in no toil.”

Yet for all the peace and beauty, the indolence and indifference of the Eloi suggested “humanity on the wane. The ruddy sunset had me thinking of the sunset of mankind.”

But this hypothesis about this future is soon to be shattered as well.

As darkness falls heralding his first night in the future, the Traveller looks down on the huge marble sculpture of a winged sphinx (part human, part animal) upon a large pedestal. He’d arrived in his time machine on the lawn in front of it. But his machine is not there.

He searches for it frantically that night, questioning the Eloi as his frustration and confusion mount, terrified that he will be marooned in this future.

The next morning he sees impressions on the grass that tell him the machine has been taken inside the pedestal, but he can find no way in.

Over the next few days he continues his explorations and observation, with the disappearance of the time machine always on his mind. He notices a number of circular wells dotting the land, and examines one. He hears a repeating thudding sound coming from below.

Among the Eloi he sees no evidence of machines, yet their clothes appear new. (He has already noted that their clothes are identical, with few clues to their gender.) He notes the absence of tombs. He has no idea who took his time machine—the Eloi seem incapable as well as uninterested.

“She was exactly like a child.” Her name is Weena, and she becomes his constant companion. She stayed especially close at night, and seemed very afraid of the dark.

The Traveller had already caught phantom glimpses of a “white, ape-like creature” in the night. Then one morning, as he escaped the heat of day (for the weather was “much hotter” than England in his own time), he entered a sheltered space and saw a pair of eyes glaring at him from deeper in the darkness.

He saw the creature clamber down the well shaft. He had met a Morlock. He began piecing together what he had observed. He realized they lived underground, that the wells were ventilation shafts, and that the thuds he’d heard were unseen machines.

So the Traveller forms his second hypothesis.

“But gradually, the truth dawn upon me: Man had not remained one species, but had differentiated into two distinct animals: that my graceful children of the Upperworld were not the sole descendants of our generation, but that the bleached, obscene, nocturnal Thing, which had flashed before me, was also heir to all the ages."

How could this have happened? The Traveller elaborates on his second hypothesis—that two species diverged from one—by speculating on the obvious parallels to his own time: the Eloi descend from the elite, the Capitalists, the Haves; the Morlocks from the servile, Labor, the Have-nots. Specifically the Morlocks descend from the workers of the industrial age, sent down for their short lives into the darkness of the mines, or into the "dark satanic mills." They are sent down there out of sight with the machinery, while the elite above enjoy the fruits of their labor.

What may appear to us now as mostly a metaphor was more powerful and shocking to Wells' first readers. The imagery of the Eloi and Morlocks resonate with us as classic caricature—boldly opposing images of fey beauty and disfigured horror out of folk and fairy tales, or religious images of angels and devils. But citizens of 19th century London could on any given day see suggestions of Eloi and Morlocks walking among them.

As several commentators suggest, the Eloi resemble the ideal look of the fashionable young aesthetes, the gentle hedonists of Aubrey Beardsley's illustrations, somewhere between the innocence of the Pre-Raphaelites earlier in the century, and the Art Nouveau of the period.

The monstrous-looking Morlocks would seem more exaggerated, but are they? Blake was not the only writer to invoke Satan. In describing workers in the mills, novelists Charles Dickens and Elisabeth Gaskell use almost exactly the same terms: that they appear as "demons among the flame and smoke" (Dickens.)

But the reality even outside the dark mines and mills was equally monstrous.

Social historian Lewis Mumford praises 19th century working class families for their heroism in just surviving, and his description of their living conditions explains why—even as it eerily suggests the Morlocks:

"…whole quarters and cities, acres, square miles, provinces were filled with such dwellings, which mocked every boast of material success that the 'Century of Progress' uttered. In these new warrens, a race of defectives was created.

Poverty and the environment of poverty produced organic modifications: rickets in children, due to the absence of sunlight, malformations of the bony structure and organs, defective functioning of the endrocrines, through a vile diet; skin diseases for lack of the elementary hygiene of water; smallpox, typhoid, scarlet fever, septic sore throat, through dirt and excrement; tuberculosis, encouraged by a combination of bad diet, lack of sunshine, and room overcrowding, to say nothing of the occupational diseases, also partly environmental."

The idea of this division was not original with Wells. Dickens wrote about it, as did Benjamin Disraeli with his famous formulation of the "two nations" of rich and poor in an 1845 novel. But it isn't just the fact of this division that Wells is exposing.

There were those in his time who believed this kind of division was regrettable but necessary—not simply that there were always poor people but that poverty and deprivation were simply part of how things naturally worked, and worked out for the best. It was survival—and triumph—of the fittest.

There were several interpretations of Darwin’s natural selection applied to human affairs that came to be known as Social Darwinism.

It was not Darwin but English public philosopher Herbert Spencer who coined the phrase "survival of the fittest." He had applied it directly to humanity a decade or so before Darwin announced his biological findings. But Spencer and others who rallied to a simplified version of Spencer’s views were eager to claim Darwin’s theory as the ultimate scientific justification.

At least implicit in Social Darwinism is that evolution decrees all-out social warfare of the strong against the weak. As unfit losers fade away, the race is strengthened because the fittest survive. Those who obtain wealth and power by any means are acting as nature intends. Large companies should not be obstructed from getting larger, and the defeated in war are to be granted no help or mercy.

|

| John D. Rockefeller |

“The laws of competition, while sometimes hard for the individual...is best for the race because it insures the survival of the fittest in every department,” wrote industrialist Andrew Carnegie. “"We accept and welcome, therefore, as conditions to which we must accommodate ourselves, great inequality of environment."

In Wells’ novel, "great inequality of environment" is exactly what could lead, in time, to one species becoming two. In his second hypothesis, the Traveller concludes this is just what happened.

He could see the process beginning in his own time, with the rich and poor separating in every way. “So, in the end, above ground you must have the Haves, pursuing pleasure and comfort and beauty, and below ground the Have-nots, the Workers getting continually adapted to the conditions of their labour.”

“The great triumph of Humanity I had dreamed of took a different shape in my mind. It had been no such triumph of moral education and general cooperation as I had imagined. Instead, I saw a real aristocracy, armed with a perfected science and working to a logical conclusion the industrial system of today. Its triumph had not been simply a triumph over Nature, but a triumph over Nature and their fellow man.”

Wells had given the adherents of Social Darwinism the world they wanted. He made their theory a fact of nature—and then he shows the consequences: two species, neither of them fully human. The fittest survive, but humanity does not.

Yet there are more surprises to come for the Traveller, along with his final hypothesis, and its proof.

No comments:

Post a Comment