Television and I grew up together. This is our story. Sixth in a series.

The quintessential English heroes have long been King Arthur

and Robin Hood.

They are foundational

legends within England and known internationally.

In the 1950s, before Lerner and Lowe’s hit musical

Camelot,

the best known of these epic heroes in the US was probably Robin Hood.

So it was fitting that the first television series centered

on Robin Hood was shot in England with English actors for an English TV network

by a production company in England. And

so it must have seemed when episodes of The Adventures of Robin Hood

crossed the Atlantic in 1955 to appear on American television.

But behind the scenes there was another story, with

different heroes. The Adventures of

Robin Hood was scripted primarily by American writers, mostly living in the

U.S. But by a particular category of

American writers.

Even at nine years old (which is what I was as the

1955 fall television season began) I’d heard about the Communist Menace. I saw headlines about it in the newspapers

and was aware of it from television.

The Sisters talked about it at school, as did occasionally the priests

from the Sunday pulpit. They called it

“Godless Communism.” The danger wasn’t

just the Soviet Union, with its atomic bombs threatening to crash down on us

while we hugged our heads under our school desks. It was also Communist subversion-- Communists undercover in our

own country.

There was a kind of hysteria, some of it organized, and an

atmosphere of fear that some stoked for their own advantages. Whatever justification there was for alarm about Soviet

subversion, a combination of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, Senator Joseph McCarthy,

the U.S. House UnAmerican Activities Committee (HUAC) and allied groups (such

as the American Legion, which led boycotts of movies, etc.) and individuals went much further in

attacking any sort of dissent, political activity or ideas they didn’t like,

for their own political—and in some cases, monetary—profit and power. Opportunism, reactionary politics,

anti-union fury and not just a whiff of anti-Semitism came to characterize this

witchhunt.

The American Communist Party was a registered political

party subject to U.S. laws, and membership in it was not a crime. None of the

accused was ever shown to advocate the violent overthrow of the US

government. In fact, those who resisted

their inquisitors did so as staunch defenders of the Constitution.

Nevertheless, these forces destroyed the livelihoods and

distorted the lives of thousands of Americans, including many with little or no

relationship to the American Communist Party, often with false and flimsy

charges and innuendo. It was cancel

culture writ large—and it affected the entire culture.

It was felt on college campuses and in schools at other

levels, in government, organized religion and other institutions and

businesses. But it had a particular

impact in arts and entertainment—to some extent in the theatre, but mostly in

the movies and television.

|

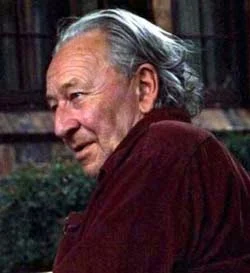

| Ring Lardner, Jr. of the Hollywood Ten |

In 1947, HUAC hearings resulted in contempt charges for

screenwriters and other Hollywood professionals because they refused to name

names of their colleagues.

The ones

indicted became known as the Hollywood Ten. They sold their homes and assets,

and (as Dalton Trumbo said later) prepared to become nobody.

They eventually went to prison for a year.

(Lardner served in the same prison as the congressman who had questioned him—he

had since been convicted of financial fraud.)

Shortly after their indictment, Hollywood studio heads met

at the Waldorf Hotel in Manhattan and issued the Waldorf Statement which

declared that the ten would never work in Hollywood again, and others who were

shown to be communists would not be employed there. This was the origin of the Hollywood Blacklist.

Though the Waldorf statement recognized how easy it would be

to unjustly victimize individuals, that’s exactly what happened. Thanks to a few powerful outlets that

published names, many were condemned for being seen with a suspected communist,

or for involvement in civil rights, civil liberties, labor organizing and other

such causes that the American Communist Party sometimes supported, or simply

for expressing a view. Or by mistake,

or for vengeance, or no reason at all except the need to continually churn out

names.

|

| Harry Belafonte |

By the mid-1950s the Blacklist was at its height. Among

those blacklisted were such well known figures as composer Aaron Copland,

conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein, band leader Artie Shaw, and folk

singer Pete Seeger; writers Arthur Miller, Lillian Hellman, Dorothy Parker,

Arthur Laurents, Dashiell Hammett, and journalists William Shirer, Charles

Collingwood and Howard K. Smith, as well as actors Judy Holliday, Burgess

Meredith, Lee Grant, Zero Mostel, and Will Geer, and director-actor Orson

Welles, directors Joseph Losey and Martin Ritt, among many others.

A conspicuous

number of Black figures in the arts and entertainment were blacklisted, such as

Lena Horne, Harry Belafonte, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson,

Josh White, Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee.

|

| John Garfield |

Many of the Hollywood actors and writers in particular were

not employed in their industry for seven, ten, twelve or more years. Others,

from big stars like actor John Garfield (who refused to name names) to many

lesser-knowns, lost their careers forever, and some lost their health, their

marriages and in a few cases, their lives to suicide. The blacklist became so institutionalized that it continued well

into the 1960s, and had lingering effects even in the 70s, long after the

McCarthy period was over.

A few

lesser-knowns got some work because of defiant directors and producers: Alfred

Hitchcock employed actor Norman Lloyd, and Robert Wise refused to drop Sam

Jaffe from the cast of the 1951 The Day the Earth Stood Still. Both became big TV stars in later decades:

Jaffe as Dr. Zorba in the medical drama Ben Casey, and Lloyd in a later

medical drama, St. Elsewhere.

And one lesser-known actor was saved by Superman. Veteran

film actor Robert Shayne was in the cast of

The Adventures of Superman,

playing police Inspector Henderson, when his wife divorced him, and accused him

of being a Communist. His offense seems

to have been an interest in unionizing.

As he was being investigated, George Reeves, Superman himself, vouched

for him. He was soon a regular on the

show.

But all of this had a profound effect on the culture of

Hollywood (which quickly made some 50 anticommunist propaganda films) and

America in general. Dissent and political activity died down, the narcosis

identified with the 1950s began. It probably wasn’t a coincidence that in the

1940s cartoons Superman fought for truth and justice, but on TV in the 50s he

also fought for the American Way, standing stalwart in front of a huge waving

flag.

|

| Brecht |

Hollywood had been energized by the artists and

intellectuals who fled from Germany and elsewhere in Europe to southern

California just before and during World War II. Now in the Blacklist 50s, playwright Bertoldt Brecht led the

exodus back the other way. But the

emigration also included Hollywood hands born in the USA. Some hid out in Mexico, and some fled to

Canada and Europe. Some didn’t come

back for a very long time.

One of these

refugees from repression was Hannah Weinstein, a journalist and political

operative who worked on the New York mayoral campaign of Fiorello La Guardia,

and the presidential campaign of Franklin D. Roosevelt. She and screenwriter Ring Lardner, Jr. wrote

speeches for Orson Welles and Charlie Chaplin, supporting FDR. All four of them were eventually

blacklisted.

But before anyone could name her name, Weinstein relocated

to Paris in 1950, and then moved to London two years later. There she established a production company,

Sapphire Films.

In 1954, legislation was passed in England to foster

competition with the state-owned British Broadcasting Company (BBC.) A private company developed by Lew Grade

called ITV was hungry for programs, especially the kind that could draw attention

and audience. Hannah Weinstein and Sapphire Films had a proposal he liked.

|

Producer Hannah Weinstein with

Robin Hood cast members |

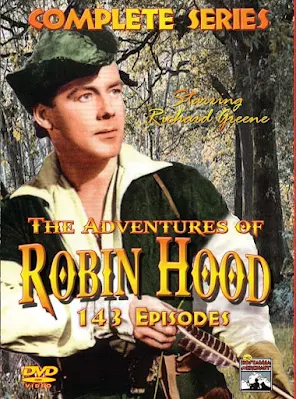

The Adventures of Robin Hood went on the air on ITV

in England on September 25, 1955, and a day later in the US, broadcast by CBS

on Monday evenings at 7:30, sponsored by Johnson & Johnson and

Wildroot Cream-Oil hair tonic. It became an immediate hit in both

countries. Its four seasons (three

seasons of 39 episodes each, one season of 26, for a total of 143 half-hour

shows) ran until the end of 1960.

Syndicated re-runs began even before the first run was over, and the

show was often scheduled for Saturday mornings, sometimes with a slightly

different title (“Adventures in Sherwood Forest.”)

It was a triumph for English folklore and free

enterprise. But The Adventures of Robin

Hood had a secret: it was written almost exclusively by blacklisted

American writers, including at least one of the Hollywood Ten, Weinstein’s

former writing partner, and Academy Award-winning screenwriter Ring Lardner,

Jr. It’s been estimated that 22

blacklisted writers worked on episodes for this show, always using

pseudonyms. Most of them still resided

in the US (some because they’d had their passports revoked.)

Their participation had to be kept secret, and it was. A

number of pseudonyms were used so that none would stand out, and they usually

were typical British-sounding names.

Moreover, the Robin Hood series was such a hit that

Weinstein quickly followed with two others widely seen in the US as well as

England:

The Buccaneers and

The Adventures of Sir Lancelot. Lancelot of course was a Knight of the Round

Table, so King Arthur (the other English hero) made it to American TV as well.

More blacklisted writers worked on Lancelot and

The Buccaneers.

Starting in 1956, we could watch Robin Hood and Lancelot

back to back on Monday nights, though we might have to switch the channel to an

NBC station at 8. Also that fall, we saw The Buccaneers on Saturdays at 7:30 p. on CBS.

This was the ironic vengeance of the Blacklist. The blacklisting authorities claimed they

were only concerned with eliminating subversive ideas from being concealed in

American entertainment, and foisted on innocent American viewers. No real Soviet propaganda was ever found

in a Hollywood film or TV show. But

thanks to the Hollywood blacklist, blacklisted writers were now churning out

stories around ideas that the blacklist promoters might well consider

subversive, and the most innocent Americans of all—namely nine year olds—were

watching them every week.

The two features that defined

The Adventures of Robin

Hood to me and my friends are the same two that likely remain in the

memories of those who watched it: the opening shots and the song at the end.

Each episode began with Richard Greene as Robin Hood pulling

back his bowstring and letting the arrow fly, with a whoosh, a whirring sound

and a vibrating plunk as it hit a tree, followed by a drumbeat and the trumpet

flourish. It was one of the most effective sounds associated with any TV show.

Then after the story came the song, sometimes just the

hypnotic chorus: Robin Hood, Robin Hood, riding through the glen/Robin Hood,

Robin Hood, with his band of men/Feared by the bad, loved by the good/ Robin

Hood, Robin Hood, Robin Hood.

By the age of nine I was playing regularly with three other

boys, neighbors on each side of our house.

Across our houses on Lincoln Avenue was a fairly large patch of trees and brush (it later hosted lots for three or four houses), that

became our Sherwood Forest. (We noticed

that the Lincoln Road passed through Sherwood, and Robin's band dressed in Lincoln green.)

We immediately got

interested in the quarterstaves that Robin and the outlaws carried and used in

their fights, and in our woods it was easy enough to find and fashion such a

staff. They made satisfying sounds when

we clunked them against one another in our simulated combat.

We actually experienced a double dose of Robin Hood in 1955.

Walt Disney made a Technicolor feature film in 1952, The Story of Robin Hood

starring Richard Todd (some of which was shot in the real Sherwood Forest), and

showed an edited version on his TV show in two parts in November. Robin Hood’s

fight with Little John on a narrow bridge over a river using quarterstaves was

more elaborate than on the TV series.

Our experiments fashioning bows and arrows were less

successful. A few years later, probably

while the Robin Hood series was still on the air, two of my friends—the

brothers who lived across a grass field to the south—were given real fiberglass

bows by their father. We set up targets

and learned to shoot a little, but we couldn’t really use them for play. None of us got good enough to even pretend

to be Robin Hood in an archery contest.

When

The Adventures of Sir Lancelot began in the fall

of 1956, we saw a different style of sword fighting—with the big flat

broadswords, sometimes with shields but sometimes using two hands. These were

also easier to simulate with wood. We also learned the vocabulary of challenge

and acknowledging defeat: “I yield.”

While all this was of first interest, the stories were

satisfying enough that we kept watching.

Unlike Superman, I’d heard of Robin Hood and King Arthur. There was a

long story in the My Book House Books volume In Shining Armor about

Robin Hood, for instance, though it was based on an older version set in the

era of Henry II. The TV series and most

modern versions of Robin Hood place him in the era of Richard the Lionhearted

(Henry’s son) and the Crusades.

Similarly, the legends of King Arthur evolved over the centuries, but

each version of Camelot sets the stage for the next iteration.

So what were the subversive ideas we innocents absorbed? The

most obvious is the best known quality of the Robin Hood legend as it developed

through the centuries: he took from the rich and gave to the poor.

That indeed was almost enough to get Robin Hood himself

blacklisted, or more specifically, banned.

In 1953 a member of the Indiana Textbook Commission called for

eliminating Robin Hood from all educational materials in the state, because

Communists were allegedly advocating Robin Hood’s income equality measures be

emphasized in education.

Although the governor of Indiana also spoke darkly of a

Commie takeover of the Robin Hood legend, the commission didn’t act. Still, the proposal inspired protest by the

“Green Feather Movement” on the Indiana University campus. Five students distributed green feathers all

over campus, with handbills explaining the issue. The local newspaper denounced them as Commie “dupes,” and the

five students were reportedly investigated by the FBI. This was the McCarthy era in small.

Of course this was all nearly 70 years ago. We’re way beyond that sort of thing now.

|

| Robin and the Sheriff (Alan Wheatley) |

In the series Robin Hood did make a policy of robbing the

corrupt rich and distributing to the exploited poor. But these acts weren’t

characterized as political. Robin

Hood’s weekly opponent, the Sheriff of Nottingham (played by Alan Wheatley)

often spoke instead of Robin Hood being “sentimental” for helping the poor or

unjustly accused, or rescuing those in trouble. It may seem a curious word now, but in the 50s “sentimental” was

another word for “womanly” or effeminate, unmanly—an echo of the implied charge

against Superman.

This Robin Hood series made it clear that the rich being

robbed were mostly those whose wealth was ill-gotten gain, chiefly by taking

from the poor. To us as children, Robin Hood’s actions just seemed fair, and as

psychologists and parents are aware, children have a very strong sense of

fairness.

But there were story points beyond this, some suggesting

issues relevant to the blacklist itself.

A central conflict of the blacklist era was between those who informed

on others, either out of conviction or to try to save themselves, and those who

refused to name names. Some who did name names (like director Elia Kazan)

ruined careers and lives. Though

blacklisted writer Dalton Trumbo famously observed that the blacklist had “only

victims,” some never forgave the informers. So as late as 1999, Elia Kazan’s

honorary Oscar was met with protests and a number of actors in the audience who

refused to applaud or turned their backs.

There were stories in both the Robin Hood and Lancelot

series that dealt with informers and traitors, the unjustly accused and punished,

all the stuff of drama and history beyond the blacklist, but pertinent to what

happened in Hollywood. Similarly, the corrupt Sheriff as well as dishonest

nobles often tried to use Robin Hood and his band as scapegoats for their own

misdeeds and swindles. It’s not much of

a stretch to see that as reflecting the views of the blacklisted.

Many more stories

concerned issues that reflected broadly applicable and widely held convictions

shared by the writers—including perhaps the kind that got them in trouble with

those in power who had a more constricted world view. For example:

In “The Salt King,” a noble with the legal corner on selling

salt creates an artificial shortage by robbing his own shipment, and then

quadruples his prices, until the outlaws of Sherwood foil his plan. In “A Tuck in Time,” Robin Hood prevents the

auction of a primitive cannon powered by “devil’s powder,” temporarily preventing

an arms race.

In “The York Treasure,” Robin stops Malbet, a racist noble

from preventing Jewish refugees from landing. Malbet gives several speeches

railing about the duty of “right thinking people” to keep out “their dirty

kind” with their “low foreign cunning,” to maintain England for the

English.

Malbet—whose actual purpose is

to steal the money that two Jewish citizens have gathered to pay for the

refugees’ passage-- is certain the refugees won’t fight back, but he’s wrong

about that.

In “A Change of Heart,” a lord refuses to allow a small band

of “primitive” Celts from remaining on their land, arguing that in the medieval

schema, they aren’t really people. With

the use of a sleeping potion, Robin convinces the lord that he is actually one

of the Celts, and soon he is arguing that the Celts have human rights, and a

right to their land.

|

| Billie Whitelaw |

There’s a preview of women’s liberation in “The Bride of

Robin Hood,” with guest star Billie Whitelaw, who would soon become Samuel

Beckett’s most important collaborator, and would star in several Albert Finney

films, especially

Charlie Bubbles.

Disguised as a boy, she saves Robin’s life with her archery

skills. Speculating on her motives for attacking the Sheriff’s soldiers, Robin

suggests she may have suffered some oppression herself. As she pulls back her hood to reveal her

feminine blond hair, she says, “All my life, beginning in the cradle as a

disgrace because you weren’t born a boy.

They think it’s a waste of time to teach you anything, and then they marry

you off without bothering to consult you.”

(However, the episode soon becomes a conventional comedy.)

Of course there were many more stories with variations on

the standard plots and conflicts, as well as other contemporary topics treated

with a light touch, as when Robin shows a pair of comic juvenile delinquents

the error of their ways, or the Sheriff lays siege to a castle with Robin

inside, where he happily cavorts with Maid Marian.

These were all in the context of adventure stories, with

battles, captures and escapes, and wars of wits between Robin Hood and the

Sheriff. There was considerable humor,

from slapstick to witty banter, aided by guest performers such as the brilliant

comic actor Leo McKern. Donald Pleasance made a deliciously evil King John in

one of five episodes directed by Lindsay Anderson, who later directed the late

1960s cult film,

“If…” that made Malcolm McDowell a star.

The Adventures of Robin Hood was filmed partly in a

British studio and partly on locations, often on the estate of producer Hannah

Weinstein. Richard Greene starred as

Robin Hood throughout, Alexander Gauge as Friar Tuck and Archie Duncan as Little John (except for the

episodes he missed because of injuries from his real life heroics, saving some

visitors to the set from errant animal actors). Alan Wheatley was the sinister but never frightening Sheriff of

Nottingham (replaced in the fourth season by John Arnatt as the deputy

sheriff), and Bernadette O’Farrell was an attractive Maid Marian (replaced by

Patricia Driscoll.)

|

| Lee Grant |

As a 9 year old, I’d heard of the Red Menace and a

little about McCarthyism, but I knew nothing about the Blacklist. Nor did I know much about it at 19, or for

some years thereafter.

In fact the

Blacklist had been lost to history until the mid-1970s, when its 1950s reality

was finally admitted. While accepting

her acting Oscar in 1976, Lee Grant was the first to mention that she’d been

blacklisted in the 50s. (Writer Milliard Lampell announced his blacklisting

while accepting a television Emmy a decade earlier.)

The first feature film about the Blacklist was released in

1976, The Front, made by a blacklisted director (Martin Ritt), written

by a blacklisted writer (Walter Bernstein), with several blacklisted actors in

the cast, including Zero Mostel.

That same year, Hollywood

on Trial, the first documentary film on the Blacklist, was nominated for an

Academy Award. It was made by friends

of mine in Boston, and I followed its process from nearly beginning to end,

viewing hours of interview footage that didn’t get into the film, and as far as

I know have never otherwise been seen.

I met several children of the blacklisted, some without knowing they

were at first, and eventually wrote about the effects on their lives. I had in

fact worked with Ring Lardner, Jr.’s son, James, a few years before knowing

much about the blacklist.

It was later in the 70s that I heard that blacklisted

writers had found work on the Robin Hood show, though it’s only been in putting

this post together that I learned many of the details.

In his Spotlight review of

The Adventures of Robin Hood,

Allen W. Wright observed, “Many children of that generation would be inspired

by this series. One professor remarked that show formed the basis of her

morality.”

"Robin Hood ran for four years, generating profits for

everyone concerned,” Ring Lardner, Jr. concluded in his autobiography, “and

perhaps, in some small way, setting the stage for the 1960s by subverting a

whole new generation of young Americans."

But though the connection to the blacklist gives these shows

a giddy emphasis and curiosity they didn’t have at the time, and while I

appreciate the ironies involved, there is the additional irony that these shows

written by blacklisted writers weren’t all that different from others we were

seeing. These were similar to stories

and themes in some other dramas and adventures we watched, including several

already described in this TV and Me series.

And maybe that’s the point.

The blacklist as it evolved was not only dangerous and destructive, it

was arbitrary and capricious. It did

needless damage that lasted for decades, both to individual lives and to movies

and the culture. But though it dampened

adult culture in the conformist 50s, it may have missed the future, thanks in

part to Robin Hood.