Newman got his PhD from Stanford University, the self-styled Ivy League college of the West, just before he began teaching at Knox, which at the time liked to call itself the Harvard of the Midwest (complete with Harvard's purple and gold.)

At Knox he was friends with Douglas Wilson and William V. Spanos of the English Department (among others), and so I probably knew of him from Wilson (my academic advisor) in my first semester. Newman and Wilson were principals in a folk music ensemble, famous that year for their satirical song about "the rug," which--if memory serves-- told the story of Knox buying the world's largest carpet and building a Fine Arts Center around it. The CFA had just opened.

But I'm pretty sure my first direct experience of Fred Newman was in the intro philosophy course (Philosophy 115) I took that second semester. I probably knew that--like my fiction-writing course with Harold Grutzmacher--it would be my last chance to take one of his courses, because it was to be his last semester at Knox. But I'm not entirely sure about the timing, since Newman himself was not told until January that his contract wasn't going to be renewed after this semester (so late in the year that it was itself a violation of rules established by the American Association of University Professors.)

A disturbing number of young and favorite faculty members were leaving Knox that year, as others had the year before and more would the year after. Newman's abrupt and mostly forced departure was the most dramatic example of the Knox brain drain, and that drama played out all semester, culminating in a Student Senate resolution and a protest march at graduation.

But while this drama slowly built to its climax, my ongoing and intensive experience was this philosophy course, the first I'd taken. It was not, we were emphatically warned, about a "philosophy of life," or even the Great Thoughts and schools of philosophy through history. Newman had studied analytic philosophy with the charismatic Donald Davidson at Stanford. Its general areas of interest were logic and language (which happens to be the title of what I believe was one of our texts: Logic and Language, an anthology of essays by the likes of Gilbert Ryle, John Wisdom and G.E. Moore.) Logic and language also happened to be areas of my intense interest and aptitude.

As I was to learn later, this brand of analytic philosophy emerged from Oxbridge--the universities of Oxford and Cambridge in England-- beginning in the early twentieth century. One emphasis among several was dubbed Ordinary Language Philosophy, which questioned academic reliance on specialized or technical terms (especially jargon) and instead analyzed the meaning of words and expressions in everyday use, and their relationship to philosophical questions.

|

| A.J. Ayer |

|

| Beyond the Fringe: Oxbridge Quartet |

That style of language and logic play also inspired the likes of David Frost (That Was the Week That Was), the members of Monty Python's Flying Circus, and Douglas Adams (The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy)--most of them Oxbridgers. It also influenced the work of several English playwrights--notably Tom Stoppard, who wrote a play about academic philosophers (Jumpers), and Michael Frayn, who wrote a long book of philosophy, which I reviewed for the San Francisco Chronicle Book Review.

This is not to imply that this philosophy course was a joke (though Quine's writing and Newman's talk could be playful and witty.) On the contrary, it was among the richest, most consequential and most intellectually mind-opening courses I took at Knox.

I remember the class as being huge. I believe we met for lectures in the Fine Art Center, perhaps the main theatre or the music theatre. The lectures were supplemented by tutorials, with either Newman or the only other member of the philosophy department, Donald Milton. Perhaps Milton lectured as well, but Newman was definitely the main attraction, a mesmerizing and theatrical performer.

We were definitely given handouts, including texts of Newman's lectures (double-spaced mimeographed purple ink copies.) I also have a long article by Warner A. Wick from the Philosophical Review that looks like it came from this course. We wrote frequent short papers, some perhaps based on articles like this, which were the subject of our tutorials.

The tutorials were held in the philosophy office where Newman and Milton would hold them simultaneously in different parts of the room. Each would be sitting in one chair, with an chair for the student opposite. We filed through, one after another. It reminded me of two priests hearing confessions, except we didn't kneel.

Philosophy 115 was not a standard introductory course that presented a range of material, organized by historical chronology or types, which students were expected to learn to identify. We were introduced instead to philosophy as an activity. We were dropped in the middle of philosophical undertakings--into what seemed like live discoveries and debates. We weren't learning about philosophy; we were learning to do philosophy.

Along the way there were new ideas and a new language, and our heads were swimming among the given and interpretive, analytic and synthetic, a priori and empirical, not to mention relativistic ontological relativism. But we learned most of the terms and ideas on the fly, inside the analyses being done. This was an electric combination.

The books and essays we read were making actual arguments to advance knowledge, as were Newman's lectures, or at least some of them. As students we were focused on Newman's preoccupations and his brand of philosophy (which I realize now in paging through two of his subsequent books, Explanation By Description and The Myth of Psychology, had American roots in the pragmatism of William James as well as certain Oxbridge figures.) But a semester is not a long time, and this approach to an introduction seems as least as valid as the more standard one.

In one sense it could be said that instead of learning the history of swimming and the various methods, we were thrown into the pool to learn how to swim. More than that, I felt it as a model completely new to me: a course in which students witness and share in the ongoing work of the teacher in their field. What could be more exciting than that?

That impression was augmented by Newman's availability. He was on campus a lot, in the Gizmo even at night, and although discussions could be wide-ranging (and funny), the kind of analytical approach we were learning in the course was always present, if not predominant. (For some reason I recall one specific day when Newman sat in the Gizmo with his back against the heat register or radiator. He talked for hours, even though he had a cold. Then he got up, declared that he'd sweated out the cold and felt better, and left.)

What were we learning? Especially what transferred beyond the discipline into other areas of knowledge and life? Of course that varied for each student. But at this remove, two areas occur to me as prominently in the mix for many.

First of all, to question, beyond what we may already have learned to question. Not just the accuracy of facts, the legitimacy of sources, the faulty arguments (by authority, for example) or illogic. But the meaning of every statement, every word--its logic and implications. Philosophy analyzed the internal logic--the hidden assumptions, the unquestioned contradictions--of entire fields of endeavor, such as science (including social science.) It wasn't a stretch to ask similar questions about politics or literary studies, or relationships.

Second, the defining role of the mind in our reality. In effect, this philosophical approach stated that the world as we know it is as much a product of the mind as the mind is of the world. In a meaningful way, we are the medium in which the apprehensible and comprehensible universe exits; our abstractions, analogies and stories construct a universe. We couldn't exist without the given world, but the world we knew couldn't exist without our mental participation. This is a paradox, and the paradox is us.

This single insight of the mind's active relationship to reality becomes crucial to approaching such disparate subjects as quantum physics, the Tao and Zen meditation, modern literature (Wallace Stevens, for instance), Vietnam and Yellow Submarine ("It's all in the mind, ya know.")

|

| G.E. Moore |

The philosophy we studied--of Quine and Lewis particularly, but with roots in Kant etc.--posits a given world, but humans define it in the most basic and subtle ways. Moreover, we don't often do this individually. Reality and its elements are a product of social agreement.

This is the subject of the one paragraph of Quine I've always remembered. He points out that calling an object "red" is a product of learning and agreement--we don't really know that everybody sees exactly the same color, and that indeed there are differences in the light that create slightly different colors, but we still call it red. Here's the paragraph (from the first chapter of Word and Object):

"Different persons growing up in the same language are like different bushes trimmed and trained to take the shape of identical elephants. The anatomical details of twigs and branches will fulfill the elephantine form differently from bush to bush, but the overall results are alike."

There was a certain shared euphoria among students in this course. I remember a long conversation with an older student named Barbara Johnson about the course that was exhilarating (and not just because she was.) This course fulfilled dreams of what college could be.

And the college was about to take it away.

|

| Paul Shepard |

At the end of the 1964-5 school year, Gabriel Jackson, widely viewed as a brilliant historian and teacher, was leaving. Student Patricia Perry wrote: "Dr. Jackson is a tremendous human being, enormously talented, interested in almost everything, with a reverence for life. He is a first-rate scholar with a concern for the humanities, for social justice, for rational and compassionate solutions to human problems. In his classes, one gets the impression of his true concern for problems that matter."

Writing professor Harold Grutzmacher was leaving, depleting the writing faculty by half. Also leaving was Rowland K. Chase, chair of the theatre department, who not only directed a stellar production of Hamlet this school year, but wrote a lecture/ essay about his approach to the production published in Dialogue--the only such occasion in my time at Knox. Kim Chase had also revolutionized the Studio Theatre program to be more student-oriented, and revitalized theatre at Knox in the process.

Some 18 faculty members were not coming back in the fall. There is always some turnover, and people have individual reasons for moving on that students of my generation were probably not equipped to understand, such as career advancement, money to raise a family, escape from Galesburg, family preferences and relationships, for example.

But some faculty exits had troubling factors in common, having to do with the college's uneven commitment to academic excellence, and conflict with the administration over policies, especially over the onerous student codes (chiefly women's "hours" or curfew, but other issues as well) that were becoming serious causes of campus conflict. Most troubling was the quality of several of the teachers who were leaving. Having experienced excellent teaching, Knox students were not happy about losing these opportunities. Many felt betrayed.

A charismatic teacher like Fred Newman would probably have been the focal point of student anger anyway, but the nature of his situation ensured it. Unlike the others leaving (who weren't on one year contracts), he had been fired--in a brutal way, halfway through the school year. Knox avoided national censure by offering him a one year terminal contract, which he refused.

The reasons for his firing were the sources of rumors all semester. In April, the editor of the Knox Student, Ed Rust, interviewed Newman, and got his version. Newman talked about the achievements of the philosophy department in a sudden array of classes and--for the first time--philosophy majors, but also disappointments and difficulties of a two-person philosophy department--requests to expand it were denied.

Then he talked about the reasons he thought he was fired. Newman was part of a group of young faculty members who worked within established channels to increase institutional opportunities for student participation in college decisions, and especially to modify women's hours, with the aim of eliminating them with a simple sign-out system for juniors and seniors.

That seemed close to success the previous spring (of 1963-64), he said, but a sudden reversal of the Student Affairs Committee vote led to alarm that the administration was closing the door on considering changes. Classes were over for the year, but students still on campus wanted to talk about this, and discuss active responses, including a demonstration at the last remaining event of the year, graduation. One of those meetings was held at Newman's home.

According to Newman, the college president (Sharvey Umbeck) accused Newman of leading or instigating this putative revolt, using a figure of speech I hadn't heard since a particular nun employed it in my fifth grade: "heads will roll." (Newman said he had opposed a demonstration at graduation, and in the end students didn't demonstrate anyway.)

Rust's interview ended with the information that the other philosophy teacher, Donald Milton, was offered a contract to stay at Knox but declined. Also that the one philosophy teacher Knox had hired to replace them had changed his mind and wasn't coming. As of April, Knox had philosophy majors and philosophy students, but no philosophy department for the following school year.

Rumors again circulated--spread by at least one administrator I heard them from--that there was more to Newman's dismissal: something so dark and sinister that it couldn't be specified. Meanwhile, the senior class "by a substantial margin" selected Fred Newman as their Senior Convocation speaker.

In May, a resolution crafted by an ad hoc student committee passed the Student Senate 26.5 votes to 4. The resolution asserted that "a valuable member of the Knox faculty has been dismissed for reasons other than his academic competence. Specifically, he is being dismissed for taking a position with respect to the social structure of Knox College, a position differing with the official administration policy." The resolution called a dismissal on such grounds "irresponsible" and "a threat to the intellectual welfare of the entire student body."

It ended with this: "We, the students of Knox College, will express our concern on Friday, May 21, 1965." That was the date of the Senior Convocation. The demonstration the administration apparently feared the previous spring was happening one year later.

The last Knox Student of the school year, also dated May 21, contained Ed Rust's editorial, stating that while claims were made that Newman was lying about why he was fired, no one offered contrary evidence. There was a long essay by student Gordon Benkler and several pages of letters to the editor, many in support of Newman as well as other departing faculty, especially Gabe Jackson.

Probably the most significant letter was from Jackson himself. He countered the charges that Newman's interview was "full of lies." There were "omissions, a few errors of detail, and some distortions of motive which understandably hurt a great many peoples' feelings--my own included. However, the interview is, on the whole, highly factual..."

Jackson's letter ended with two sentences that would reverberate for years to come: "I do not know the extent to which the administration and trustees are determined to create a great liberal arts college at Knox. I do feel that I know that a truly excellent faculty and excellent student body cannot be maintained within the present codes."

This issue of the Student also contained the text of Newman's speech to the Senior Convocation, entitled "Rules and Games." It was reprinted a year later in Dialogue. Reading it today, it remains well-cadenced, eloquent, heartfelt and insightful. It is personal and at the same time creates a thoughtful context for the 1960s but also for our densely computerized age.

It continued themes of our course as well as a theme of the year for me--the defense of individualism. Individualists, he said, are aware that in "acting in accordance with existing norms" they are choosing to endorse these norms, and are "sensitive to the fact that these norms are, in part, a result" of their choices. Norms or rules cannot become moral crutches.

"Individualism needs defending," he said. People can "dehumanize" themselves.

Aspects of the address are also very interesting in light of Newman's own later career. At the time, with its evocations of Wittgenstein, it continued and--for those of us who were his students--completed our course in philosophy.

I don't remember much about the actual demonstration that spring. In memory I thought it happened after the graduation ceremony. I seem to recall being in Seymour Union to get my picket sign, waiting for it to start. I remember it as being silent--a long line, single and double file--more of a funeral procession than a raucous demo. Or maybe that's what I felt--that it was a funeral for my Knox College hopes, for the possibilities I saw in the course I'd just experienced, that seemed to be taken away in the next instant.

Effects of this philosophy course and the events of that spring--personally and at Knox more generally-- continued into the next year. I intend to pick up the story in a future post.

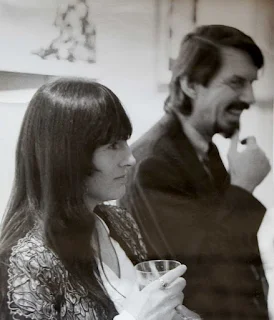

As for Fred Newman, by that late spring I'd established something like a personal relationship with him. He volunteered to drive me and my boxes and suitcases of stuff to the Q train station to send home for the summer, in exchange for my babysitting for an evening so that he and his wife could go to what amounted to a farewell party.

We exchanged a few letters (though none survive), and I saw him occasionally over the next three years. He seemed to come back to Galesburg at about this time every spring, including 1968, when the last students who'd had him as a teacher were about to leave. It was perhaps the year before that he arrived a little later, when Galesburg was already gripped in its solid block of summer heat. Probably my last memory of him was outside the apartment where I was staying on West Berrien. He'd been in a mood, almost hostile at times, alternating with gloom. I saw him sitting on the hood of a car, looking into the sunset.

|

| CCNY today |

Once when he returned to Galesburg he was promoting his new idea, an independent program called the Robin Hood Relearning Corps. He also mentioned a summer experiment, in which he and three other philosophers and their spouses lived in the same house, so they could do philosophy full time. The only result, he said, was that all four marriages broke up, including his own.

By the 1970s he was out of academia, and those two anecdotes suggest directions his life would take. I remember him once cursing psychologists as "failed physicists," an offhand remark that continued to seem apt in many ways. Just as his philosophical mentors claimed that reality is socially obtained, he decided that psychology required a social practice. He and others developed a new kind of therapy, at least partially based on some of the theories that got attention in the late 60s, such as the work of R.D. Laing in the UK. He became a therapist, with highly controversial methods. Some of his work on personal and social development was with underclass black and Latino youth.

Newman also became a player in New York politics (he ran for Mayor at least once), and a playwright with his own theatre. I have no personal knowledge of any of this, so I'll just quote his New York Times obituary:

"Fred Newman’s influential role in New York life and politics defied easy description. He founded a Marxist-Leninist party, fostered a sexually charged brand of psychotherapy, wrote controversial plays about race and managed the presidential campaign of Lenora Fulani, who was both the first woman and the first black candidate to get on the ballot in all 50 states.

He helped the Rev. Al Sharpton get on his feet as a public figure and gave Michael R. Bloomberg the support of his Independence Party in three mayoral elections, arguably providing Mr. Bloomberg’s margin of victory in 2001 and 2009.

He created an empire of nonprofit and for-profit enterprises, including arts groups and a public relations firm. He wrote books on psychology and philosophy as well as plays. One play, about the 1991 riots between blacks and Jews in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, was condemned as anti-Semitic by the Anti-Defamation League.

His greatest impact came through mobilizing his followers, sometimes called “Newmanites,” to build alliances with third parties, including that of the Texas independent H. Ross Perot."

When I heard about his death after a long illness at the age of 76 in 2011, I looked up this dizzying information: he's got a wikipedia page as well as his own website and material on the East Side Institute site. He's got his own Vimeo page and C-Span page of videos. I can't comment on the insights he had on psychology and politics, or dramaturgy for that matter, since I haven't really perused them. But I did see that he continued to have enthusiastic followers whichever way he turned.

I began to see Newman not as a phony or a charlatan, as he has been called over the years, but as a charismatic personality, and as much a captive of it as others were captivated.

I've known other people since with similar traits: that brilliance that focuses with complete belief, together with an insistent persuasion and cultivation of complicity--until they drop it and pick up something else with the same conviction.

This is not necessarily bad but can be dangerous. Generosity is accompanied by a need for the emotional connivance of others, and at worst there is a blindness to consequences and disparagement of non-believers.

The first effect of that charismatic energy, to quote a multi-year student of Fred's, was a kind of ecstasy: "I fell completely under his spell." But also: "Fred left quite a trail of victims, and quite a trail of followers." This former student detached himself from Newman's orbit when he began to see destructive consequences, long after he left Knox. In similar circumstances, others apparently either overlook or rationalize such consequences, or believe they are not primarily consequences of what the charismatic figure said or did. Or they remain so convinced or just overwhelmed by the brilliance and the vision that nothing else matters as much.

His complexities, it seems to me, don't require condemnation, just wariness. Specific actions or ideas can be evaluated on their own. The charismatic personality is hard to resist but can become stifling as well as exhausting, so sometimes--or maybe inevitably-- you eventually just have to move on. But the words are still there to be read and considered.

The Newman I knew introduced me to Quine and Wittgenstein, and to seeing the world in a different way. In "Rules and Games" he quoted Wittgenstein about what games had in common--don't think or assume you know, but really look. Newman also said of his speech that he wished he'd been asked "to hear for you rather than talk to you." Those two statements remained guides for me and my work from then until now.

The 1965 Fred Newman ended his Senior Convocation Address by returning to Wittgenstein, and his last words: "Tell them I've had a wonderful life."

"Even those who never understood were to be thanked for allowing him to rant and rave and to be his individualistic brilliant self," Newman said. "I am surely no Wittgenstein and I do not believe I am about to die. But I feel compelled to conclude by saying to all my friends who have understood as well as to those who gave me the opportunity to persuade, 'Thank you.'"