Science fiction is a method, a way we see the future—a kind of storytelling by which we imagine, evaluate, contemplate the future in something close to a usefully comprehensive way. Some argue that, in our age, it is the only possible way of envisioning and interrogating the future.

So what is it?

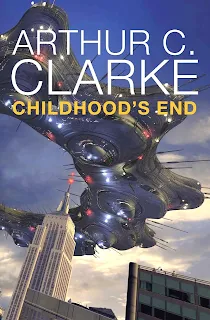

"Attempting to define science fiction, " wrote science fiction author and futures studies pioneer Arthur C. Clarke, "is an undertaking almost as difficult, though not quite so popular, as trying to define pornography."

After reviewing distinctions and definitions, Clarke finally allows that “it is, preeminently, the literature of change...”

Others tend to agree. Though he has his own technical definition, science fiction writer and historian Brian Aldiss wrote, “The greatest successes of science fiction are those which deal with man in relation to his changing surroundings and abilities.”

“Science fiction accepts change as the major basis for stories,” Lester del Rey assented. Author James Gunn called “a belief in a world being changed by man’s intellect” the “one indispensable ingredient of science fiction.”

Historically it was a response to “the conclusion that change was now going to be man’s fate, and that if he wished to be the master of change rather than its victim he would have to start thinking about the consequences of his actions and decisions,” Gunn concludes.

Change implies a difference from the past and especially the present, which seem to be known quantities. The past however is deceptively solid, its actual ambiguity revealed by changing interpretations of past events. (For example, various “objective” accounts over the years have depicted General Armstrong Custer as the hero, villain or fool of Little Big Horn.) The present is circumscribed by what we know and accept, not necessarily all that there is. Like the future, neither past nor present is known or stable.

Nevertheless, a fiction of the future seems fanciful to many, and disturbing to some. We know the present involves change, but we naturally try to maintain stability. Fast changes are upsetting, in reality and emotionally. Otherwise, our experience of the slowly rolling present lulls us into assumptions of permanence. (If this seems not to be a contemporary affliction, consider the fortunes always lost when an ascending stock market fails to keep rising and shockingly plunges.)

Science fiction however (as Mark Rose writes) “challenges our sense of the stability of reality by insisting upon the contingency of the present order of things. Indeed, science fiction not only asserts that things may be different, as a genre it insists that they will be and must be different, that change is the only constant rule and that the future will not be like the present.”

This has been true since its beginning. According to science fiction scholar Darko Suvin, “Wells’s basic historical lesson is that the stifling bourgeois society is but a short moment in an unpredictable, menacing, but at least theoretically open-ended human evolution under the stars.”

However scary it might be, and however preposterous stories of the future appear, looking towards the future is a human attribute. An argument can be made that honing abilities to be curious about the future, to imagine and plan and create a future, are key characteristics of a developing human species.

Such curiosity and wonder are within us still. They are so strong that we thrill and are beguiled by the basic question that every science fiction tale poses: What if?

Because new technologies and how people use them constitute such a crucial determinant, and because fiction is often best equipped to explore possible uses, implications, ramifications and effects on individuals and society within a complex context of life as it is lived, science fiction is the best lens on the future.

Or as contemporary science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson suggests, double lenses. Because fiction (or any form of speculation) cannot entirely escape its origins in the present, and because it is often metaphorically a critique of the present to various degrees, it is a lens on the current world and its place in history. But in depicting changes and resulting patterns and relationships, science fiction is also a lens on a possible future.

Understanding science fiction is a matter of seeing through these lenses simultaneously—as most science fiction readers and viewers informally learn to do. The result is a perspective that glimpses possible futures as well as seeing the present from a different point of view.

The double vision of science fiction to simultaneously view the present and future (both with their implied pasts) is only one of its characteristics that mediates, combines and synthesizes otherwise separate categories.

In fact a key characteristic that enables it to depict present and future simultaneously is the combination implied in its name, the label that Gernsback gave it: science fiction. It brings science to fiction, and the tools of literature to science.

Those tools include not only the logic of stories and the repertoire of literary effects, but the observations and insights we may now associate with the social sciences of psychology, sociology, anthropology, which study aspects of life first examined in literature and storytelling. Literature also traditionally applies philosophic points of view.

Partly because science fiction is informed by a literary sensibility, it can depict change not just as a linear way forward, not simply as progress, but also as cyclical, or as repeating aspects of the past in a new guise. Or even as retrogression, as in The Time Machine.

Fiction brings the human element, the persistence of underlying social and cultural systems, to technological change. Literature applies vestigial beliefs, human needs and emotions, patterns and archetypes to imagine effects of the sudden products of science.

Seen broadly as a popular as well as refined art, literature (including various kinds of stage plays and their descendants in newer media) can examine and express all levels of experience.

"Science fiction, we have been in process of discovering for some years now, is not the tawdry, sensationalist literature of the half-educated inhabitants of a roboticized society, but rather one of the few authentic mythologies of the twentieth century, a reexamination of the most ancient psychic dilemmas in the vocabulary of a distinctively contemporary world-view, “ writes Frank McConnell.

“To describe it as a mythology, moreover, is to imply that, at least at its best, science fiction bridges the gap—otherwise a widening one in our [20th] century—between so-called popular culture and so-called high culture.”

It is in popular culture that the pulp era assumes special significance, particularly in expressing unconscious fears and desires concerning the future—as will be explored in later posts in this series.

Yet science fiction also represents the relatively new approach of science—not only new technologies as subject matter, but science as a point of view.

In both areas—literature and science—the model is H.G. Wells. “The question most asked about science fiction is: ‘But is it literature?” notes Sam Moskowitz in his history of science fiction, Explorers of the Infinite. “To this, the science fiction world has one powerful and overriding answer, and that answer is expressed in the name of H.G. Wells.”

As for science, “Wells was the first significant writer to started to write SF from within the world of science, and not merely facing it,” writes Darko Suvin.

Wells applied science to human history to envision the future as partly the product of changes in the past and present. And he wrote about the future using the tools of literature, from describing effects on ordinary people to applying metaphors and creating a literary structure. Most serious science fiction follows both of these models.

By combining aspects of literature and science, science fiction mediates between crucial elements of human concern at all times, but essential to considering the future. “Science fiction’s role as mediator between the spiritual and the material is in alignment with its role as mediator between the human and the nonhuman,” Mark Rose observes.

Such a mediating and synthesizing in humans is, according to some contemporary commentators like Thomas Moore and James Hillman, a function of soul. According to the tradition they follow, mediating body and spirit, thinking and feeling, are the defining characteristics of soul.

Given the role of science and technology, mediating, synthesizing and simply exploring the relationship between science and the provinces of literature are essential to imagining, considering and creating the future.

"If our art…does not explore the relations and contingencies implicit in the greater world into which we are forcing our way, and does not reflect the hopes and fears based on these appraisals, then the art is a dead pretense,” wrote scientist Hermann J. Muller, discoverer of the genetic effects of radiation, in 1957. “But man will not live without art. In a scientific age he will therefore have science fiction.”

What then are the futures that science fiction imagines? There are many and yet, there are only two.

To be continued. For earlier posts in this series, click on the "Soul of the Future" label below.

Origins: The Winter Solstice

-

The Winter Solstice is considered the most celebrated annual event in the

history of human cultures around the world. Ancient structures survive in

m...

2 weeks ago

No comments:

Post a Comment