H.G. Wells: In the Days of the Comet

Though the space alien invasion is now a familiar story type, The War of the Worlds is the first one known. To create it, Wells combined and transformed two popular topics of the time.

The first was the result of a growing anxiety across the western world. After decades of peace, European nations were taking advantage of new technologies and industries to make many new and more powerful weapons for mechanized war. In 1871 an anonymous pamphlet described a future invasion and conquest of England by a barely disguised Germany as if it had already happened. (The author was later identified as George Tomkyns Chesney, a former Captain of the Royal Engineers.)

“The Battle of Dorking” became a sensation throughout Europe. It inspired a spate of similar novels dramatizing invasions of one country by another that were still appearing in the late 1890s.

Another popular topic was the planet Mars. What geology was to the first years of the 19th century, astronomy became to its last decades. Bigger and better telescopes and new instruments led to discoveries that inspired public enthusiasm. So many amateur astronomy societies arose that the British Astronomical Association was formed to organize them in 1890.

Particular interest was focused on Mars, due to discoveries made each time its eccentric orbit brought it closer to Earth. As a result of his 1877 observations, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli published maps of the Martian surface which showed a network of lines he called “channels.” But the Italian word (“canali”) got translated as “canals,” and since manmade canals were familiar features of the industrial age, a roar of speculation resulted concerning past or present intelligent life on Mars.

Mars was even closer in 1894, and American astronomer Percival Lowell professed to see even more evidence of canals, which he believed were the work of a civilization desperately trying to irrigate their drying planet.

Also that year, French astronomer Javelle reported “strange lights” on the Martian surface that might be signals. These were taken so seriously that eminences such as Edison, Marconi and Tesla tried to devise ways to signal back.

All of these sensational reports and the keen public interest they generated resulted in at least 50 novels about Mars and Martians.

None of the Mars novels or the invasion novels (with the possible exception of Chesney’s) were very good. But H.G. Wells saw the potential of putting these two topics together, in the first invasion from space story: The War of the Worlds, serialized in 1897 and published in book form in 1898...

He goes to see it, and is in the crowd when the Martians first appear, and witnesses the first deadly use of their heat ray. He is sufficiently alarmed to take his wife to a nearby town for safekeeping, in a borrowed horse-drawn cart.

At first it is believed the Martians are trapped in the pit, but when he gets back to Woking (to return the cart) he is confronted by their giant Fighting Machines, which stride through the countryside incinerating people and buildings with their now-mobile heat ray. Meanwhile, other cylinders are falling to Earth.

Those 1894 lights on the Martian surface, he surmises, were the first blasts of the guns that would send these cylinders across space in a planned invasion.

|

| a more contemporary illustration |

Our chief narrator has encounters with two less than exemplary humans, the Curate and the Artilleryman, and witnesses the Martians feeding on the blood of live human victims.

With the human race on the run all around him, he blunders into London, where he watches the defeat of the otherwise indestructible Martians, by bacteria to which they have no resistance.

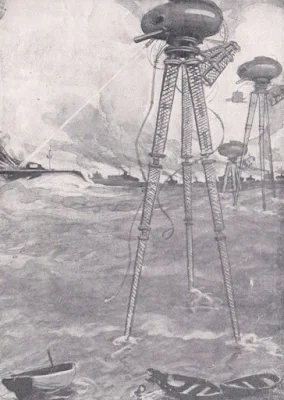

|

| a 1915 illustration |

Since the book was published in 1898 and takes place in the 20th century, it qualified as future history for those first readers as well.

Though it is clearly if subtly stated early in his account (and referred to later) that humanity survived the invasion, Wells’ precise description and evocative invention create a compelling and suspenseful narrative experience.

This novel ominously forecast the near future of warfare, from the poison gas of World War I to the effects of bombing and invasion of civilian areas (“Never before in the history of warfare had destruction been so indiscriminate and so universal”) that would characterize World War II, lacking only the inhuman enemies from another planet.

It is also his first to foreshadow technologies of future weaponry—from manned flight to the laser-like heat rays—as well as still speculative uses of cybernetics and psychic communication.

The War of the Worlds repeats and extends several themes of The Time Machine. First, it continues Wells’ challenges to the complacency of his time. “The War of the Worlds like The Time Machine was another assault on human self-satisfaction,” he wrote in his preface to a 1934 collection of novels. Human mastery has not been attained and progress is not inevitable. In this case, humanity is challenged not by another species rising from beneath it on Earth, but by an alien species of greater power coming down from outer space.

To understand this possible fate, Wells suggests the people of his time and place might need to see things from another point of view, such as that of the invading Martians. Several times the narrator suggests understanding how the more advanced Martians might see humans by recalling how humans see ants or small animals.

|

| 1905 |

This act of imagination seems to have been the seeds of this story. As Wells recounted in a 1920 article of the Strand magazine, he was walking with his brother Frank “through some particularly peaceful Surrey scenery.” They were probably talking about the indigenous inhabitants of Tasmania, an island south of Australia, who were nearly eradicated when the English turned the island into a prison colony. Then his brother wondered, what if some beings from another planet suddenly dropped out the sky and did that to England?

Frank Wells made the first imaginative leap, the empathy of placing himself in the position of another who is perceived to be very different. For this idea, H.G. dedicated the book to Frank, and made a very specific analogy early in the story: “The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?”

There are several more references to oppressed people overrun by empires, and the theme is sounded early, with a clever use of the word “empire” and a reference to indigenous peoples such as American Indians and Africans who find themselves beset by missionaries:

“With infinite complacency men went to and fro over this globe about their little affairs, serene in their assurance of their empire over matter. It is possible that the infusoria under the microscope do the same.... At most terrestrial men fancied there might be other men upon Mars, perhaps inferior to themselves and ready to welcome a missionary enterprise.”

The Martians have as well the same excuse as humans of Wells’ time used: imperialism is actually natural selection. The Martian race was older and much more advanced. “And we men, the creatures who inhabit this earth, must be to them at least as alien and lowly as are the monkeys and lemurs to us. The intellectual side of man already admits that life is an incessant struggle for existence, and it would seem that this too is the belief of the minds upon Mars.” Again there is the Huxley version of a relentless evolutionary process, which only human ethics and empathy can counter.

But as advanced beings, wouldn’t Martians develop such ethics? This leads to a third theme—perhaps the most subtle and devastating. As an older race, the Martians have had longer to evolve. The beings they have become are physically simple, pretty much just a large head and hands (or more precisely, tentacles.) Though resilient, they are weak. Their strength is in their machines.

To make the game of identifying with the Other more explicit, Wells’ narrator notes that “a certain speculative writer of quasi-scientific repute, writing long before the Martian invasion, did forecast for man a final structure not unlike the actual Martian condition.”

That writer was Wells himself. In his 1893 article “Man of the Year Million” he speculated that, having long before delegated all physical activities to their machines, humans of the far future would become nothing but head and hands. Here he also suggests that with the body gone, the intelligence becomes unfeeling, like the Martians who in the famous opening paragraphs of The War of the Worlds are “intellects vast, cool and unsympathetic.”

This is the fate of humanity when it becomes dependent on technology. These Martians are us. Humanity is being conquered by its own future.

Like the Morlocks in The Time Machine, the Martians are technology-minded beings who raise a biped species as food—they use tubes to extract their blood. Eventually they then do the same to live humans: the first interplanetary vampires. (Bram Stoker’s Dracula was first published at about the same time as The War of the Worlds.) This is the sole relationship to organic life of this technologically dependent race. Both the Morlocks and the Martians are versions of the human future.

This dehumanizing effect of technology is another theme that will become prominent in the twentieth century. Wells, the biologist and prophet of technology, explores the complex relationship of the machine and the organic in the lives and future of humanity and the Earth.

In The War of the Worlds, the war is won literally by the Earth itself, and by humanity’s long biological relationship to their planet. The Martian machines are defeated when the biological beings inside them die from infection by bacteria to which humans, after many generations of suffering and death, have become immune.

That in the end, it is the organic that saves humanity and the Earth, says quite a bit. It is first of all, almost literally grounding. It is evidence of the realities of dependence, of relationships to the Earth and its organisms that technological humans ignore, partly as expression of the same arrogance that leads to complacency, partly as denial.

With Wells, the machine enters literature as a given, as part of reality. The relationship of man and machine, the machine and nature, and generally the impact of science and technology on human life and the human future, would come to define a new kind of fiction.

Wells set the template for this kind of fiction with the novels and stories he wrote in the first decade of his career. He called them “scientific romances.” It would be nearly 30 years before they would be known by the name we call them today: science fiction.

Not all science fiction stories are directly about the future. But in one way or another, nearly every story about the future is within the realm of science fiction. Its unique history and status is essential to understanding how we confront the future.

To be continued. For prior posts in this series, click on the Soul of the Future label below.

No comments:

Post a Comment