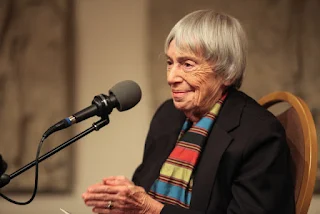

I'm not entirely sure why I take the death of Ursula LeGuin in such a personal way. I have no right to--I attended a reading she gave at a Portland bookstore some 20 years ago, but other than that, I didn't know her.

I haven't even read many of her books, though I remain enormously impressed with one of them, Always Coming Home. It's so unique I can't get past it to her other created worlds. It's not one of her best known, though it is singled out in the emotional tribute by writer John Scalzi that appeared in the LA Times. He notes the immediate and heartfelt response of so many in the literary world and especially the science fiction and fantasy universe who did know her:

"On and on and on goes this immediate and real-time outpouring of grief and remembrance of a woman who gave us Earthsea, "The Left Hand of Darkness" and the short story "The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas," which is as much a parable for our time as anything that anyone has written, or likely will.

She was a supporting column of the genre, on equal footing and bearing equal weight to Verne or Wells or Heinlein or Bradbury. Losing her is like losing one of the great sequoias. As the unceasing flow of testimonials gives witness, nearly every lover and creator of science fiction and fantasy can give you a story of how Le Guin, through her words or presence, has illuminated their lives."

I responded so strongly to Always Coming Home as a vision of a far future that is a complex return to a humanity living in close relationship to the Earth, with a strong relationship to Indigenous and particularly Native American culture. As well as being a woman writer in an historically and predominantly male sci-fi culture, what distinguishes her is a background in anthropology. This goes back to her father, Alfred Kroeber, who wrote several works on California Indians, and her mother Theodora Quinn Kroeber, who wrote Ishi in Two Worlds, a classic about the last member of his tribe. This is a crucial perspective for the future. I probably also felt an aspirational kinship because she was from California, at a time when I was making it my home.

Probably the personal quality of my response is also due to large extent because I've been reading her latest book, No Time To Spare, which is a collection of short pieces she wrote as blog posts. Though she applies her keen intelligence to literary and political matters, much of the book is personal, about her life and her attitudes toward life, specifically her thoughts on aging. In that way it is intimate, and in some ways it's like I've been in conversation with her, off and on, since I bought the book at a bookstore in Menlo Park on Christmas Eve. A Christmas gift for myself.

The title essay took to task a familiar sounding questionnaire from her alma mater of Harvard for her sixtieth reunion. They wanted to know what she did in her spare time. Something she shares with another great woman when she was in her 80s, Jane Jacobs, is that she won't let a stupid question or sloppy statement just go by. She found this one pointless. "What do retired people have but 'spare time'?"

It's all spare time--except that none of it is: "I still don't know what spare time is because all my time is occupied. It always has been and it is now. It's occupied by living."

Maybe that's also part of it. She was so vibrantly alive. Selfishly, she was a source of hope.

I've read some of her other nonfiction--her essays collected in The Language of the Night (1979), the essays and speeches collected in Dancing at the Edge of the World (1989.) There have been other collections and nonfiction books since, in addition to a wealth of fiction and poetry.

Her now famous National Book Awards six minute speech in 2014 accepting a lifetime achievement award (which I posted here) was a two-part poem. The second part warned against trends in publishing that shifted autonomy and power from writers and editors to the sales department. By accepting this, writers are giving away their most precious asset--their freedom.

The first part was acknowledging that writers in fantasy and science fiction are finally being accepted in the literary world, which I hope is true. Back in the 1970s she was already making the case for why this is necessary, also in a speech accepting a National Book Award (in childrens lit): "Sophisticated readers are accepting the fact that an improbable and unmanageable world is going to produce an improbable and hypothetical art. At this point, realism is perhaps the least adequate means of understanding or portraying the incredible realities of our existence."

I suppose I wasn't completely unprepared for news of her death. Her blog was ongoing but when I checked it online, she hadn't posted in months. She was 88, my mother's generation (or anyway, the generation of her younger brother, my uncle.)

But it was a blow I'm not over. After all, I'm still reading her book. I had intended to start a series of quotes from it here. Maybe I'll start with this one, from a piece about a holiday visit that involved young children.

"What it made me think about above all is how incredibly much we learn between our birthday and last day--from where the horses live to the origin of the stars. How rich we are in knowledge, and in all that lies around us yet to learn. Billionaires, all of us."

May she rest in peace. Her work lives on, and on and on.

No comments:

Post a Comment