In the burgeoning controversy over e-cigarettes, this and similar stories caught my eye: a congressional hearing exposing how e-cigarette sellers were marketing specifically to young people, by using social media but also by handing out free samples at music and other events that attract the young.

It reminds me all too well of similar efforts in the late 1980s and early 90s when I was a columnist for a weekly alternative newspaper in Pittsburgh. It was in fact called In Pittsburgh, and it was mostly of interest to a young adult readership. At one of my frequent lunches with the editor-publisher, he informed me that the paper had been offered two very large new ad accounts, both from cigarette companies. One of these companies was buying multi-page inserts three weeks out of four. But they had a condition: no anti-smoking stories or words could appear in that issue. The editor was telling me because I'd already written such columns, and he was accepting the ads and their conditions.

As shocking as this was, I was even more surprised that I was virtually alone in seeing it as betraying basic journalistic principles. If anyone else connected with the paper thought so, they didn't say so or do anything about it. For some at least it was a small inconvenience for a greater good. "All I know is that I'm getting health insurance," was one comment I recall.

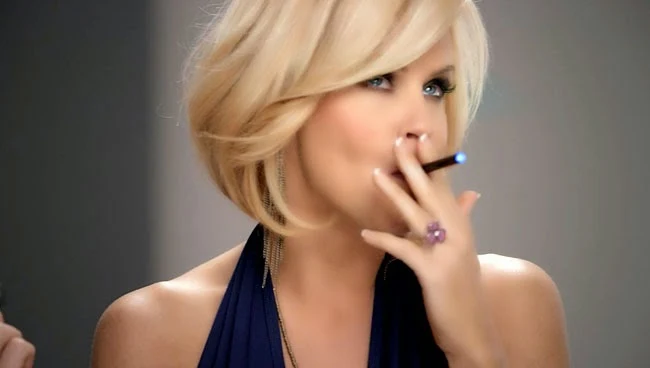

At about the same time I went to a local club to hear a band--some place I went to fairly often, and where I usually saw a lot of people I knew. There were Salem cigarette banners everywhere. At the door to the dance floor and performance area, young ladies in fetching green and white outfits stood with trays of cigarette samples. And what was the reaction? I heard somebody say how flattering it was that a national brand was paying attention to a club in Pittsburgh.

I soon wrote about this event and the compact that my newspaper had made, knowing that the column would not be published and that I would resign in protest, which is how it played out. I got no support from "friends" on the paper. There suddenly appeared letters in the daily papers ostensibly from other writers for the weekly (though I'd never seen the names before) criticizing my action. I got no support from anyone in the Pittsburgh press or media. Along with my gig and my readership, I lost pretty much all of my friends.

There were a number of lessons I learned from this, about habitual ways of thinking (no one connected this with censorship, although the usual suspects were up in arms when someone was prevented from describing a sexual act on the radio), about the power of money to corrupt and compromise at any level, and about costs that never quite end. Some of this informs my understanding of reactions to the climate crisis.

But some of it of course bears directly on this current e-cigarette situation. This time however reaction time has been at least a little quicker. It didn't take as long for a congressional hearing and substantive political opposition. And today the Food and Drug Administration is exploring rules governing e-cigarettes as well as other new tobacco products. It's been a 5 year struggle to get that far, and the proposed rules don't do much to restrict marketing to youth. But that's par for the course. It wasn't until several years after my confrontation that the FDA finally declared that nicotine is a drug that it could regulate.

Update: However, the FDA action may not be all that it seems, judging from this Wall Street Journal article: "Makers of electronic cigarettes breathed a big sigh of relief Thursday as the Food and Drug Administration avoided a heavy-handed approach to regulating the fast-growing alternative to traditional smokes, likely paving the way for stepped-up investment and even more varieties."

Several years ago I wrote an anti-smoking musical for school children (never produced) that included the figure of Moloch representing the cigarette companies. Moloch mythologically is a demon who devours children. He's apparently still working for tobacco interests, although he's branched out since then, considerably.

Starting With Stoppard

-

Tom Stoppard died in November 2025. From his first success in the late

1960s--*Rosencrantz and Gildenstern Are Dead-*- to now, I followed his

career and...

2 weeks ago