Growing up most of a continent away, there were always some books in our house (though none in most other homes I visited), and I always had books to hold and look at. I had Golden Books of the 1950s, and other child-size books like Little Toot and The Little Red Caboose. But I also had a library of particular book-size books. My first house of books was My Book House.

Officially called The Book House For Children, they were illustrated anthologies of verse and prose edited by Olive Beaupre Miller and published under its own imprint in Chicago. The first set came out in a series beginning in 1920, and some version would continue to be published until 1971.

Writer Jim Harrison, a few years older than me, wrote about the influence of this set on his childhood. And fellow western-Pennsylvanian Mr. Fred Rogers remembered an even earlier encounter--right down to a particular story read to him as a very young child.

The set that I grew up with was published in 1943. The prior 1920s editions were six thick volumes but by the 40s the same basic material was in twelve volumes of more than 200 pages each. They were deep blue, thinner but larger in size to better accommodate illustrations.

We had fifteen books in all, for the set included a Parents' Guide Book and two extra volumes, the orange Tales Told in Holland and the lighter blue Nursery Friends From France, both unchanged from 1927, when they accompanied the original sets as "My Travelship." There was a third Travelship volume called Little Pictures of Japan, but I don't recall we had it, possibly because it wasn't offered in 1943 since the US was at war with Japan.

Our set must have been acquired at my birth in 1946. I believe my mother's sister Antoinette, who was a teacher, either gave us the set or advised my mother to buy it. It became central to my childhood and that of my sisters, Kathy and Debbie. I have the set now, and evidence of each of us survives in the books themselves: my scrawls of the alphabet and attempts to print my name in pencil and crayon, a number of blank endpapers in the Parents' Guide volume decorated with Kathy's drawings, and a clutch of napkins stuck in one volume upon which Debbie wrote and drew--and signed, when she was seven.

We were not the only ones who grew up with these books, of course. In recent years they've become a favorite of home schoolers. Writers remember them. Novelist Jim Harrison mentioned the Book House set several times in his fiction and nonfiction. Larry McMurtry writes a few words about it in his autobiographical Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen, which I've recently read and which prompted these musings on my early experience with books.

For me now, the color, slight shine and heft of these volumes, the very touch of their cool surfaces, still define "books." As I view their contents, browsing by the light of the floor lamp that had once been in my grandparents' living room, now nearest to the shelves where these books repose, I can be taken back to earliest impressions, especially by the relationship of these evocative, colorful and now singular illustrations to the text.

|

Once I'd learned to read I don't recall my mother offering any guidance as suggested, but she seems to have heeded some of the suggestions on reading to babies. (I have the advantage of having my own very real memories confirmed by watching her with my younger sisters, particularly Debbie, who was born when I was 8.)

For example, the book suggests how to hold a baby's arms and clap while mother recites "Pat-a-cake, pat-a-cake, baker's man" (which sounded more like "patty-cake" to me) and how to play with the babies toes for "This little piggy went to market." It's exactly how my mother did it, although she sometimes added a rhythmic bouncing as she held me on her knee, which I believe was important in showing me that whatever else words in such arrangements were about, they were first of all about rhythm and music.

Since my mother's own babyhood was in Italy and the Italian language, and I was the eldest child of two eldest children in the vanguard of my generation, I believe she was following this book's instruction, including gradually getting me to chant along, and to anticipate the words and rhymes. The rhythmic bouncing, however, was probably homegrown. Since I remember my grandmother doing that with us, she probably had done so with my mother. But other instruction she ignored, just as we ignored many of the other selections in that first volume, In the Nursery.

When I look at them now, I feel the resonance of their magic then. Like the animals around a music stand under the verses about the sounds they make ( Bow-wow," says the dog; "Mew, Mew," says the cat; "Grunt, grunt," goes the hog; And "Squeak!" goes the rat.) Or the cow flying over the moon accompanying "Hey diddle diddle," the subject as well--as my mother once pointed out to me--of our cookie jar.

After fifty pages of common nursery rhymes, there are successive sections of short rhymes from Scotland, Wales and Ireland; Norse, Italian, Spanish, Swiss, South American, Mexican, Polish, Swedish, Chinese and East Indian nursery rhymes, and one Japanese lullaby, before national and regional rhymes from America, including American Indian Songs.

Then another set of short sections of German, French, Dutch, Czechoslovakian, Canadian, Russian, and Hungarian rhymes, and a Roumanian lullaby. Rhymes from Finland, Africa; rhymes from Shakespeare, verse from Keats, Robert Burns, Tennyson, Christina Rossetti, Robert Lewis Stevenson.

Some of the verses get longer before the book turns to prose, and explores childhood experience in a neighborhood, on a farm, in a big city and so on, sometimes in stories similar to those found in an early grade reader, sometimes adapted from authors like Hans Christian Andersen. Ending up with tales from Greece, Rome and the Bible. All in this first volume.

This resolute international inclusiveness, the combination of folk stories, myths and work of classic authors, set one pattern for further volumes. Olive Beaupre Miller would change the mix over the years, but this edition seems to preserve some authentic cultural fragments, perhaps otherwise lost, with no apology for how puzzling many selections were and are.

Some stories have morals and messages, but they aren't all "The Ugly Duckling" and "The Little Engine That Could" (which are included.) The one that stayed with me is "The Gingerbread Man" (who in the story is called the Gingerbread Boy.) The Gingerbread Boy comes to life, leaps out of the oven and over 8 madcap pages inset with illustrations, he laughs and outruns everybody. Until the last page when he reaches the river, still being pursued, and accepts the fox's offer to carry him across on his back. As the water gets deeper the fox counsels him to jump up on his shoulder and then his nose, until the fox eats him.

Not exactly a strive and succeed sort of story, but the impact of it hit me with the final illustration. Most of the figures had been cartoonish, except the fox in the final one, which is rendered with startling realism. I'm surprised now to see how small this illustration is, down at the bottom of the page, because it made a big impression on me, when my mother read me the story.

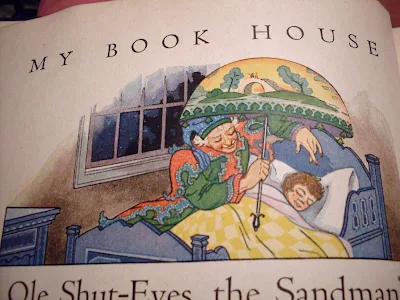

The illustration in this book I most loved however was of the Sandman holding his wondrous umbrella over a sleeping child. The umbrella reminded me of a similarly shaped and decorated lampshade on a table lamp at my grandparents. (I believe my sister Kathy has it now.)

Volume 3, Up One Pair of Stairs was transitional--I remember reading parts of it myself. I learned to recognize words on my own, but didn't really read until taught to do so in first grade, where I was in the Rosebuds reading group, the most advanced one. We started with the classic Dick and Jane readers, though possibly a Catholic edition.

This volume of My Book House has more and longer prose stories, and the illustrations have changed. In the first two volumes the colors were bright and varied, with variations of reds. Though I believe they all were done with a four-color process (illustrations using similar colors appeared together), the palate mostly became restricted in this and subsequent volumes to shades of blue and orange as well as black and white, and more like art deco. They were less prominent usually, deferring to the text, but not always.

By volume 3, the books in my set are also in better shape, showing less handling than the first two. Now I seem them as treasuries, but at the time they competed with schoolbooks and later with comics and library books. But I did read selections in all of the volumes, often in bed and especially when restricted to bed by my many childhood illnesses (mumps, chicken pox, measles twice as well as colds, flus, etc.)

In volume 4 (Through the Gate) I'm sure I read about Paul Bunyan and Pecos Bill, Johnny Appleseed and the Fisherman and His Wife, a cautionary tale about greed.

Volume 5 (Over the Hills) wove in more history, with several pieces about Abraham Lincoln (and the Gettysburg Address verbatim), along with Jack and the Beanstalk, a poem by Emerson, and William Dean Howell's "The Pony Engine and the Pacific Express" (I especially loved stories about trains, like those I could see a few blocks from my grandmother's house.)

Volume 6 (Through Fairy Halls) emphasizes magical worlds, though hewing close to impressive classical sources, such as libretto for operas, a tone poem by Debussy, Shakespeare (prose telling of A Midsummer Night's Dream) and Dickens, and stories about Leonardo da Vinci and composer Felix Mendelssohn. The versions of stories we would know in more popularized form like Hansel and Gretel and Sleeping Beauty are closer to original sources. Again, a mix of international tales, including Alaskan, Hawaiian, Northwest and Winnebago Native tales, and poems by Basho and Eugene Field.

Now when I browse subsequent volumes I see poems, excerpts and rewritten tales from authors and works I've since read. If I read these as a child, their influence was subconscious, but then much of education is. There are bookmarks left in them (one indicating 1962) by one or another of us.

The one volume I remember best is the eighth: Flying Sails. At some age--perhaps 11 or so--I became passionately interested in tales of ships and the sea, and voyages. And of all the stories in this volume, the one I recall definitely reading first there is "Gulliver's Travels to Lilliput."

Comparison to Jonathan Swift's text shows this to be only lightly edited and condensed, so Swift's voice is preserved as well as the now classic story. Again I remember reading it here because I recall the illustrations. But these illustrations are not so numerous, and the story lasts for some forty pages. The point being that while I was transported by the wonder of the story, I was given the opportunity to absorb its literary merits as well.

Volume 12 (Halls of Fame) is devoted largely to biographical sketches of authors, including authors of famous fairy tales with suggestions of their hidden historical references. It notably includes a long, illustrated retelling of Goethe's Faust. This final volume ends with an index to the entire set, plus a child development index that sends the parent or reader to appropriate pages for views on bravery, courtesy, imagination, shyness etc.

These books existed in my life within a context that prominently included movies (especially Disney), radio (early on) and television, as well as phonograph records. (I still have my battered 78 version of Tubby the Tuba.) But the point is that books were represented, and not just picture books or school books (which barely registered as books.) My Book House provided living examples of what books are, and the template for my further and continuing explorations of these nurturing, magical objects.

I may have begun to learn to read when my mother read from the early volumes of the Book House, and in other ways a pre-school child picks up the shape of letters matching with words in advertisements, etc. But mostly I started in first grade, where we read a Catholic-approved version of the Dick and Jane readers. We had a large class (in the same classroom as the second grade, so I listened to their lessons, too) and were split into reading groups, with the names of flowers. I was in the top group--the Rosebuds. These books had their own odd poetry of repetition, but I recall being energized in third or fourth grade when the readers suddenly took on new life, and there were verbs liked "zipped." Eventually we got lists of vocabulary words, which to me were like new worlds.

Another influence had to be our main text, the Baltimore Catechism, with its question and answer guide to Catholic doctrine that provided another repetitive cadence. Our Catechism had a cover with white figures on a blue background.

Throughout twelve years of Catholic school, the day began with the entire class standing and reciting from memory a parade of prayers--the Our Father, Hail Mary, Glory Be, Apostles Creed and the Confetior (in addition to the Pledge of Allegiance to the flag and another to the Cross.) Throughout grade school we attended Mass one day a week in addition to the required Sunday, and adjourned to church to say rosaries and perform other rituals, all of which involved reading and reciting verses and prayers, with their imagery and particular language. We did not read the Bible per se, but we certainly got major parts of it in the Epistles and Gospels at Mass, and chunks of the Old Testament in school. It wasn't exactly the King James version, but close. So these and their particular cadences and vocabularies were repeated experiences in my reading.

No comments:

Post a Comment