“And the roses of electricity still open

In the garden of my memory.”

Apollonaire

|

| photo by Paula Rhodes 1974 or 5 |

At the end of March 1974, after I returned to my Cambridge apartment from my mother’s funeral and the eight weeks in Greensburg that preceded it, I started a new notebook.

On the first inside page I wrote: “Write of other worlds, not this one.” I didn’t attribute it, but it was (as only I knew) one of the last things my mother said to me, in the midst of a stream of consciousness goodnight.

I recorded my state of mind and the state of my affairs as April began. Though I had many acquaintances beyond my apartment’s walls, I was more alone within it than ever. My last housemate was moving out, to live with a new group of friends. My time was untethered by any particular responsibilities other than the flexible mealtimes of my cats. Various tensions from those weeks at the hospital and then the funeral (the slow motion loss, the guilty tedium, the sense of unreality in the midst of as real as it gets) were releasing, accompanied by unpredictable physical ups and (mostly) downs. Plenty of tensions remained. Yet I was not unhappy, I wrote--though too much was lost and was otherwise missing for happiness either.

I was still collecting unemployment checks for a few more months, and had some savings left, so I resolved to work hard on my college novel. I had worked out a plan and written about 80 pages the previous year, and now I would write to that plan—25 pages a week was my goal: 300 pages by my birthday at the end of June. Though that still would be a fraction of the plan.

I had plenty of doubts. Could I? Should I? Was I crazy to try, especially without support or encouragement of any kind? Could I find the necessary temperament, the energy combined with the stillness? What could I draw on, in this Cambridge of ambition and acquisition, of drive haunted by compromise, of ego and insecurity and the reflexes of angst, of feckless frenzy and rolling confusion?

These doubts were never really resolved and haunted me from time to time. At other times I was entirely absorbed in what I was doing.

I was buoyed a bit by a used copy of a book titled The Rise of the Novel by Ian Watt, originally published in the late 50s and kept in print by the University of California Press. It chronicled and analyzed the early English novel in the 18th century, of Defoe, Richardson and Fielding. Looking at it again now, I feel the same excitement at the birth of something new that was derived—and often improvised-- from many older sources, yet was particular to the time.Among the characteristics Watt named as distinguishing the novel from other forms was especially relevant to my project: “…the novel, whose primary criterion was truth to individual experience… which is always unique and therefore new.” I was also encouraged to learn that Daniel Defoe had begun as a journalist, essentially writing his own periodical, including reporting on crimes, something else that was relatively new in his time.

Another characteristic of these early novels, Watt writes, is embedding the characters in a particular time and place. Fielding seems to have regularly consulted an almanac to keep tracks of days and dates, as well as external events such as the Jacobite rebellion of 1745. This is something I learned from James Joyce, and it was especially important for my college novel, given that 1965 was so different from 1967 as to be almost another planet.

Also important to me, perhaps indirectly but very strongly,

were the books about early to mid 20th century art in Europe,

primarily in Paris. I had art books

from Phoenix days and a few before that (mostly to do with Picasso.) Now in the many Cambridge bookstores I

searched for books of text as well as reproductions. I often got them used or from bargain bins and hurt books

tables. I was especially alert to

volumes in the paperback series Documents of 20th Century Art: Dore

Ashton’s book on Picasso, the memoir of a major modern art deader in Paris,

dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Apollonaire on Art and a volume on Italian

Futurism. Dada and Futurism led me to French Surrealism, which had its literary

expressions and tradition.

Also important to me, perhaps indirectly but very strongly,

were the books about early to mid 20th century art in Europe,

primarily in Paris. I had art books

from Phoenix days and a few before that (mostly to do with Picasso.) Now in the many Cambridge bookstores I

searched for books of text as well as reproductions. I often got them used or from bargain bins and hurt books

tables. I was especially alert to

volumes in the paperback series Documents of 20th Century Art: Dore

Ashton’s book on Picasso, the memoir of a major modern art deader in Paris,

dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, Apollonaire on Art and a volume on Italian

Futurism. Dada and Futurism led me to French Surrealism, which had its literary

expressions and tradition.

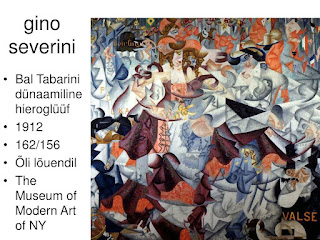

My identification with this place and period was both

vindicated and greatly strengthened when I came upon the name of Gino Severini,

as a painter and theorist of Italian Futurism.

When I mentioned him to my grandmother, she immediately recalled a

conversation she’d overheard many years before, among her husband’s Severini

relatives, about the black sheep of the family who had run away to Paris to

become a bum. The time fit pretty exactly,

and a penniless painter, even with famous friends (including Picasso and

Apollonaire) and future fame himself, would fit the bill as a bum.

My identification with this place and period was both

vindicated and greatly strengthened when I came upon the name of Gino Severini,

as a painter and theorist of Italian Futurism.

When I mentioned him to my grandmother, she immediately recalled a

conversation she’d overheard many years before, among her husband’s Severini

relatives, about the black sheep of the family who had run away to Paris to

become a bum. The time fit pretty exactly,

and a penniless painter, even with famous friends (including Picasso and

Apollonaire) and future fame himself, would fit the bill as a bum.

Now it seemed I had blood in the game. I visited the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan (on a press pass) every time I was in New York. Besides buying one of the few books on Futurism then (derived from one of their exhibitions) I could see several Severini paintings, including the largest and most famous: Dynamic Hieroglyph of the Bal Tabarin.

It was about this time that I added Severini to my byline name (though at first only to my “literary” efforts), mostly to honor my mother and her family—for that had always been more the family than my father’s—but I was also linking myself to Gino. When years later I read his autobiographical books, I felt even stronger resonance.

This—along with writing poems and plays, writing songs and playing music—constituted my creative life. I pursued possibilities to extend it, by going through the laborious process of applying for fellowships (I recall going to the Harvard Square Xerox place to pick up my bound manuscript for the annual Massachusetts Arts and Humanities Foundation grants, and seeing under the harsh florescent light the stacks of other applying manuscripts the night before deadline) as well as sending out poems and the occasional story: except for a single prose poem published in a local literary magazine, without success.But I also pursued opportunities in the areas I had established some credits, a kind of journalism. I knew little of career-building, though I was soon to see how it could work as I watched friends and former colleagues swiftly ascend to the heights, but I did intuit (rightly or wrongly) one path I might follow: from writing for city weekly periodicals to national magazines, and then to book contracts.

By this time I was mostly trying to write for magazines. I had written for Creem (I have an undated letter from the legendary Lester Bangs, probably from the previous year, encouraging me to re-start my relationship there. “I think you’re one of the best writers who has appeared in this magazine,” he wrote. I don’t think anything came of this, though I’m not sure why.)

But I had also entered the big time magazine world with an assignment from Esquire in 1972. I’d been called by a young editor there named John Lombardi, who liked something I’d written for Creem (I’m guessing it was my review of the early apocalyptic movie Omega Man starring Charleton Heston) and he probably found me through its editor, Dave Marsh. He wanted me to research and write a story for Esquire’s annual college issue on one of Harvard’s better known dorms, Adams House, that was now co-ed (radical for the time), and especially the rumor that their swimming pool included nude bathing. Without ever actually witnessing such an event, I did some interviews (yes, they said, but the nude swimming was no big deal), wrote the story and it was published.After I left the Phoenix in 1973, I learned from Dave Marsh that Lombardi had moved to Oui Magazine, a new glossy from Playboy, and they were assigning. I proposed a story on a singles cruise that advertised itself as employing computer matching, a hot trend of the time. He assigned it, and off I went that December.

It turned out to be mostly bogus: the computer matching was a fraud (so much so that the guy doing mine offered to “hand select” anyone who’d caught my eye) and the singles theme hadn’t filled the boat, so there were families as well. But by the time I realized this, we were on the water and I was trapped for the week. We hit rough seas in a relatively small ship and this absurd floating imprisonment became a sickening one as well. Still, I did get paid to visit Puerto Rico and St. Thomas-- for an hour each, but a memorable hour. I wrote the story but in early 1974 the magazine had wisely passed on publishing it.

In addition to my excesses in response to the Phoenix and other separations in 1973, I was walking a lot more and lost weight I’d acquired from hurried restaurant meals, helped no doubt by the fact that for the first time I was dependent on my own cooking. I also quit smoking, which set off a series of revelations.

I discovered I was less addicted than habituated, so I was able to wean myself off cigarettes by concentrating on my primary smoking circumstances. So instead of a cigarette next to the typewriter when I wrote, I kept a bowl of popcorn. To accompany drinking, I chewed gum, or on Twizzler-type licorice. That these were awkward substitutes was part of the plan. I could soon do without them, though I kept the popcorn for awhile.

In social situations I especially noticed the way smoking cigarettes became part of people’s conversational style—the pauses for inhaling, the cigarette itself “as a baton at the end of our gestures.”

So while I was in Greensburg those eight weeks, I wrote an article about quitting smoking and these observations, and sent it out. By spring it had been rejected everywhere. The dependence of magazines then on the revenue from cigarette advertising I’m sure had nothing to do with it. But this attempt did start something in my professional life: the impetus for an article was my own experience.

My most promising new contact probably came through Janet Maslin, friend and former colleague at the Phoenix, who had been spreading her wings beyond that paper when I was editing there. Now she was the regular music columnist at a new magazine in New York called New Times (unaffiliated in any way with publications of that name since.) She was pals with the film reviewer who also was an editor at the magazine, Frank Rich. She suggested I get in touch with him—perhaps to review books. I did, and in February I had heard back. They had more book reviewers than books to review, he said, but he encouraged me to send article ideas. I did but with no success yet that spring.

So while I continued to write pieces for the Real Paper locally for a little income (and go through hell to get paid) I had little excuse not to organize my life around writing those 300 pages of fiction.

And so I did—with days of lethargy and nights of elation, 18 hour binges of work and sleep, with stretches of numb despair and high anxiety. But as the clock struck midnight on June 30, 1978—my 28th birthday—I had produced those 300 pages, or near enough.

I recorded this in that blue notebook while sitting in the place that had become the center of my life outside my apartment: the Orson Welles Complex, specifically this time, the Orson Welles Cinema lobby.

I could say that the three overlapping, interacting, competitive, conflicting and symbiotic parts of my life were creative, professional and personal. I’m not going into much detail about the particularly personal here, but it’s fair to say that significant aspects of all three did their dance at the Orson Welles Complex, especially in these years.

When I first arrived in Cambridge in 1970, the Welles was a single-screen cinema on Mass Ave between Harvard and Central Squares. Cinema blossomed in those early to mid 1970s, with the availability of foreign films, the rediscovery (partly through the enthusiasm of French New Wave directors) of past decades of American films, a surge in creative Hollywood films and a growing recognition of film as art. There was a surge as well in film schools and courses (though I didn’t know it at the time, the Orson Welles itself had a film school.)

My devotion was guaranteed in that spring of 1970 when as part of a Godard retrospective, I saw Pierrot Le Fou three times, including the last screening in a mostly empty theatre with only hardcore fantatics, accompanied by the aroma of Gaulloises.

A few years later—certainly by 1973—the Welles Cinema expanded to three screens, descending in auditorium size but not in quality of viewing. This was also still the era of the double feature, except for some first run theatres. So on any given day, there were six movies playing at the Welles. At its height, on Saturdays with morning screenings and midnight shows, there might be ten.

So for the first five years of the 1970s, I had a cinema experience and film education that is unimaginable now, just as it would have been unlikely if not impossible before. I saw probably hundreds of good if not pristine prints of a wide variety of movies, well-projected, on big movie screens. I saw new movies there, though not the same ones at the Boston commercial chain theatres. More like Lucia, a Cuban film, or The Harder They Come, the Jimmy Cliff movie from Jamaica that introduced reggae music to many, which ran at the Welles for a year or so.

The Welles was one of four movie theatres in Cambridge, all of them showing foreign films at least some of the time. But the Welles had the most films, especially in organized retrospectives. It was mostly there that I saw almost all of Truffaut and Godard released to that point, a lot of Bergman, Fellini, Renoir, Kurasawa, and of course Orson Welles. Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast, Orpheus, Blood of the Poet. Hitchcock’s early British films, Chaplin from The Gold Rush to The Great Dictator, City Lights, Modern Times and Limelight (which had been banned until 1972.) I saw what was available of the astonishing early French filmmaker Abel Gance, the definition of innovator and the avante garde, including a version of Napoleon (with some scenes split into three screens) and the 1938 version of the antiwar J’Accuse, much of it shot in World War I, featuring a harrowing scene of men who were really about to go into battle with many likely to die, essentially playing their own ghosts. I believe there was a documentary on him as well, perhaps the 1968 The Charm of Dynamite.

Black Orpheus, The Blue Angel, Rene Clement’s Forbidden Games, Louis Malle’s Murmur of the Heart, De Sica’s Umberto D. Wuthering Heights, The African Queen, Borsalino, Bicycle Thief, Savage Messiah, Straw Dogs.

There were Bogart, Garbo and Brando retrospectives, the classic Cary Grant and Kate Hepburn comedies, and in the full flower of their 1970s revival, all the Marx Brothers movies except their first, The Coconuts, not yet available then. There were comedy festivals, one which included Richard Lester’s non-Beatles movies, The Knack, the surreal How I Won the War, and the even more surreal The Bed-Sitting Room. |

| Gena Rowlands in Faces |

Stan Vanderbeek was one of the experimental filmmakers who came to show and talk about their work. Robert Altman was hot in the 70s—I saw The Long Goodbye and McCabe & Mrs. Miller there. I remember documentaries on and starring Henry Miller (The Henry Miller Odyssey) and Anais Nin (Anais Nin Observed.) And I’ll never forget seeing Night of the Living Dead for the first time there, and hearing for the first time in any theatre the screams of adults watching it.

As part of my cinema enthusiasm, and especially under the influence of Truffaut and Godard, who always showed books and characters reading in their films, I started collecting film books, in the same way as the art books. I was drawn mostly to books on the French New Waves and its directors, but there was a lot of other writing on film at the time.

I particularly collected book versions of film scripts, which often included stills from the film, and sometimes interviews and criticism. Most of these were in the Modern Film Scripts series, but there were others. Bergman’s and Truffaut’s filmscripts in particular became available in hardback and paperback editions. I saw these books for the first time at the f-Stop camera store that was attached to the Welles for awhile.Though we had the privilege of seeing these films on the big screen, we could only see them when the cinemas exhibited them—there was no video of any kind, and foreign films were rarely on TV, almost never with subtitles instead of dubbing. So these script books were all I could keep. Now with so much dependence on streaming and the disappearance of art film cinemas and video stores, when once again most of these movies aren’t readily available, these books are again all I have of them, unless I have the DVD or they are on YouTube.

I was writing and editing at the Phoenix when I met Larry Jackson, manager of the Cinema and the one who selected the movies shown. Later he was the manager of the entire Complex, but still programmed the films. (Martha Pinson succeeded him as manager before she, too, moved to the administrative offices upstairs as publicity director, and Mary Galloway took over.)

|

| me at the typewriter some years later in that t-shirt. Photo by Elizabeth Offner. |

By the time I left the Phoenix we’d become friends, and he continued to include me in Welles film activities. For instance, in 1974 I got to hang around “backstage” with Peter Bogdonavich and Cybil Shepherd when they introduced their film version of Henry James’ Daisy Miller, and accepted some semi-silly award from Harvard students. I saw fame from a different perspective: both of them were near-sighted, so the crowds around them were mostly noise and a blur. I thought it was admirable how they could keep their composure.

.jpg) |

| Orson Welles and Larry Jackson, 1976? |

Another of these forays however gave me one of the greatest cinematic experiences of my life: a 1974 screening, probably at Boston University on a portable screen, of the as-yet unreleased new Cassavettes film A Woman Under the Influence, starring Gena Rowlands in a transcendent, bravura performance (which eventually led to an Oscar nomination.)

The lights came up after this very powerful film to show Rowlands and Cassavettes standing in front of the screen. For a mind-bending moment it seemed she had just stepped out of the movie. I asked a question from the crowd, struggling with emotion, and I saw the empathy in Rowlands’ eyes. Afterwards, on the sidewalk outside, I met them both.

|

| Martha Pinson at the snacks counter |

Most often I was just drinking coffee and starring off into space or scribbling in my notebook, as I was at the clock struck twelve, inaugurating my 28th birthday.

I was there so often that Mary or Manny would enlist me to help take tickets when several movies were starting at the same time. My conversations upstairs with Larry included my suggestions for films to program (my greatest triumph: the double bill of Morgan! and Charlie Bubbles, two of my idiosyncratic favorites of the 1960s British New Wave) and eventually led to becoming the co-editor of the program book for the 1974 Boston Film Festival there.

I was not the only one to be obsessed with film—the cultural moment might be indicated by the fact that Jon Landau gave up editing the record review section of Rolling Stone and writing about music there, to become its film critic. I recall at least one movie we saw together at the Welles—it was a Welles in fact. He claimed to have seen 300 movies in one year. Thinking about it, I probably came close. I did have it bad. One Saturday, starting with the morning show at the Welles, I saw 10 movies in one day, including a few on television… And then I was sick in bed for a week.By late fall in 1970, the Orson Welles Restaurant opened. It seems to me the bar on the level above it didn’t open until some time later. In any case, when I wasn’t at the Cinema, I was opening the thick wooden doors to the bar, which wrapped around and looked down on the restaurant below street level. I ate at the Restaurant a few times—almost always the duck with orange sauce—but that was for special occasions. If I ate there it was in the bar, where they served from the lunch and dessert menus. Together the cinemas, the restaurant and the bar comprised the Orson Welles Complex.

The social life of film and the Welles continued there. In addition to Larry Jackson and Terry Corey, who also worked upstairs, I met other film buffs, some of whom were engaged in filmmaking. I even ran into David Axlerod, who started me on my cinematic journey with the Cinema Club at Knox College; he was in Boston for day or two, so naturally he stopped by the Welles.

|

| David Helpern, Jr. Photo by Paula Rhodes |

David had just finished a one hour documentary film on director Nicholas Ray, whose most famous films included Rebel Without A Cause, Johnny Guitar and two Bogart films, In A Lonely Place and Knock On Any Door. It was called I’m A Stranger Here Myself, which the documentary noted was what Ray said was the working title of all of his films, and appears as a line in Johnny Guitar.

Nicholas Ray had a tumultuous and colorful career, often at odds with Hollywood, but his movies were admired by film buffs, particularly the critics and directors of the French New Wave (a short interview with Francois Truffaut appears in David’s film.)

David had an even longer history with the Orson Welles Cinema than I, having been (I believe) both a student and teacher in its film school. (He was later co-editor with me of the 1974 film festival program.) He involved several people from the Welles in making his film, including Murphy Birdsall (production assistant), and he acknowledged Larry Jackson, John Rossi and the Welles in general in the credits. His producer was Jim Gutman, who had been the chief administrator of the film school.To introduce his film, he got Nicolas Ray himself to spend a few days in Boston. At the time Ray had been teaching at what was then Harpur College (where my ex-prof William Spanos taught), and is now the State College of New York at Binghamton. Much of the documentary follows Ray as he works with students on making an actual film, part of which was later shown at Cannes.

David invited me to tag along with him and Nick Ray, so I was present for all his public events, his radio interview, and shared a couple of meals with him. (One evening he and I were the last to leave the table. At the time, the price of sugar at the grocery store was very high, so as we left I pocketed a few of the small bags of sugar at the table. He was amused by this, and pocketed some himself.)

Ray was known as an especially sensitive director (he had a close working relationship with James Dean) and a sensitive man. His talks were sometimes halting, but concise and articulate. Hearing him speak softly about the ideals of filmmaking and art in general to a scattering of attendees after a very late screening in the Welles’ smallest theatre was almost a religious experience.I scribbled down one line: “Wherever you go in the world, the principal concern is ‘Who am I? Where am I? Why am I?’ We need to find ways to say hello to each other and look one another in the eye. To dream and try things.”

He was 63 but seemed older, very weathered, but with a corona of white hair and the remnants of a noble face. (He’d started as an actor, and would soon appear in Wim Wender’s film, The American Friend.) He smoked incessantly, but what I didn’t know is that he was struggling with, or in the grips of alcoholism and drug dependence. A few years later he was diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer. He died five years after his days in Cambridge.

But the Orson Welles bar was more than a hangout for film buffs and those engaged somehow in movies, with ambitions for some sort of film career. It was presided over by a cadre of waitresses, the most beautiful young women I’d ever seen in one place, and they were there every night. I got to know some of them to some extent, so Buffy, Celine, Emily, Emily, Kathy, Laurie, Lori, Marie, Martha, Teri and others were my ambiguous Muses.

Cambridge was deep in the throes of absorbing new mores and conditions brought on by the early 1970s women’s movement, known then as women’s lib. I had many conversations with other young men there—some of them complete strangers—about the confusions and ironies arising from that new consciousness, which had become for some men a nearly paralyzing self-consciousness. We noted for example that while we were supposed to be getting in touch with our feminine side, we were watching some of the women of the Welles going off with men on motorcycles.

Meanwhile my professional life was reviving somewhat. In August I got a letter from Frank Rich responding favorably to an article idea for New Times, and book review assignments from Suzanne Mantell at the new Harper’s Bookletter, a publication of Harper’s Magazine.

My New Times idea resulted from a report I must have stumbled on, of research that found a biological basis for why some people like to stay up late, as I did, and it was a revelation. The majority of people are born Larks, who are energetic early and then fade; a minority are Owls, whose body temperature rises slowly, so full energy doesn’t arrive until later. I fit the Owl profile exactly—so it wasn’t a character defect but a matter of biorhythms.

It got me thinking about other elements of the built environment that affect people but aren’t recognized as having effects, like lighting and temperature. I might well have been thinking of my response to the awful lighting in the hospital where I spent so much time, and how my father kept the house heated too high for my comfort that winter. Relating all this to people’s behavior and self-image, especially in the workplace, could be the basis for an article. I don’t recall if I had to write a formal proposal but I eventually got the assignment.

I did maybe a half dozen reviews for Harper’s Bookletter, the most notable being a plea to get Paul Shepard’s Man in the Landscape back in print. I complained—as I often did, and would again--that the editing had taken out my writing voice.

I don’t think the Bookletter lasted very long, but I have kept one with Lewis Lapham’s cover essay on “The Pleasures of Reading.” He was then the editor of Harper's. “On first opening a book I listen for the sound of the human voice,” it begins. "Most books don’t have it, but there are still so many that do." It’s a long and lovely essay; I read Lapham every month in Harper’s as well as some of his books. I met him briefly in his Harper’s office in the 1980s, and he was a friendly generous and open man as well as a writer always worth reading.

Books I was reading other than those I was paid to read evidently (from notes) included: Don DeLillo’s first novel Americana; a selection of Kafka short stories, and Conversations with Kafka by Gustav Janouch; a novel I loved entitled Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things by Gilbert Sorrentino, which I picked up off the remainder table at Reading International. I wrote Sorrentino to express my admiration. He wrote a gracious letter in return, urging me to keep writing despite the difficulties.

Also that year, Neil Young came to the Orson Welles with his first movie, Journey Through the Past. I saw it at the press screening, and when the two weeklies panned it, I wrote a letter to the editor to both papers. They were both music critics, and suggested Young stay in his lane. I suggested they both do the same, for it had cinematic qualities, however unconventional, that they failed to mention. I praised the cinematography and especially the sound, and called it authentic and surprising. I recall Larry Jackson saying that I was the only writer who understood the film.

But they carried the conventional wisdom, and today it’s known mostly for the concert footage, especially from Buffalo Springfield, but there are sequences with Hollywood actors and one very visual scene that came directly from one of the director’s dreams.

During the screening I sat in the aisle seat of the third row, and I could see Carrie Snodgress, Young’s partner at the time, and their two year old son Zeke standing near the side curtain by the stage and the screen. I was absorbed in watching the movie when I felt a tug on the fringe of my jacket. I looked down to see Zeke, with Carrie close behind him, taking him away.

I was wearing my suede jacket with the fringe—I’d always wanted a fringe jacket like those I’d admired on The Range Rider and other childhood TV heroes, though this one had the added advantage of thick fleece lining against the Massachusetts cold. Neil Young wore a more classic fringe jacket in some album photos. That’s what I immediately thought of at the time—that Zeke had seen the fringe jacket and headed straight for it.

|

| Neil Young, Larry Jackson and Manny Duran in the OW lobby |

“The Loner,” he said, considering it. He soon did release another live album, and “The Loner” was on it.

After dinner, I was among the party that piled in a car or two and headed up the coast to a roadhouse bar where a local band was playing. Again we sat around a long table, now drinking beer. I somehow wound up playing pool with Neil Young, a game I know nothing about except that, in my experience, a certain reckless confidence works wonders. So it was this time, and I won (though really, only because he scratched.)

We were still there when the band ended their final set, and one of Neil’s guys told them that Neil would like to jam. They refused. The guy put a $50 bill on the drumhead as they were packing up, but the answer was still no. For some reason they gave up the chance to jam with Neil Young (maybe they were pissed that we made noise during their sets), and we lost the opportunity to hear him so close up.

We headed for the car and the long drive back in the dark. On the way, Neil spotted a lighted cross on a hill or atop a church and said that kind of thing freaked him out. Crosses were evident in his movie, too, especially as carried by the Klan. Back in Cambridge the Welles people and I were dropped off in front of the Cinema. I tried saying goodbye to Young but he was glowering straight ahead, somewhere else entirely.

I did have another rock and roll moment, though it was more in the nature of a non-encounter. Janet Maslin invited me to grab a sandwich with her and then go to the Bonnie Raitt concert at the Harvard Square Theatre. We ate somewhere in Harvard Square, and she explained that her husband Jon Landau was meeting with the opening act, a band starting to make some noise fronted by a guy named Bruce Springsteen. He was frustrated because he felt their first couple of albums, which didn't sell well, had been badly produced, and Jon had helped make Jackson Browne a star by producing his breakout album. But my conversation with Janet was so irritating and exhausting that I decided to just go home. I'd seen Bonnie Raitt several times so I thought it was no big loss.

A few days later the Real Paper published Jon Landau's column that began with the most famous words in rock critic history: "I have seen the future of rock and roll, and it is Bruce Springsteen." Some of the column was personal and heartfelt, but it was that sentence--bannered on ads--that has lived on. Landau's prophesy was a bit self-fulfilling, in that he did produce Springsteen's breakout album, Born to Run, and later became his manager. It would be several years before I saw Springsteen live, at a theatre in Pittsburgh, and it was amazing. But I missed my chance to be present for the concert that made rock history.

I returned to Greensburg in August for the wedding of my sister Debbie and Jerry Boice. Their reception happened to be on the evening of my high school’s 10th anniversary class reunion. So with two of my Central Catholic friends, Clayton and his wife Joyce, who were also at the reception, I headed a short distance down the highway to check out the free gathering in the bar of the restaurant where the reunion dinner would occur. Since I had dated Joyce in high school, she reveled in the idea that people would be wondering which of us she was married to.

I saw that the cheerleaders etc. of our class were now sleek married women, and most of the guys were already overweight. I spotted one former friend who’d been timid and socially backward who was now a prestigious professor with that ageless middle-aged bearded look of the academic, standing aloof in the shadows, long drink in hand. We didn’t stay long.

When I got back to Cambridge I found that my apartment had been broken into. Among the stolen items were various stereo components and, adding insult to injury, my typewriter.

I continued to be absorbed working on the novel, completing another two or three hundred pages of first draft by the end of the year. But money was getting tight. So I tried to concentrate on paying work.

In late fall I was researching the Larks and Owls article for New Times, finding relevant research and professional sources to talk to. Except for the ensuing phone interviews, I worked in the Widener Library at Harvard, with breaks at Harvard Square cafes. Once at my favorite Patisserie (as I recorded in a notebook), I could overhear two conversations at nearby tables—a couple was talking about places they’d lived, while two women were discussing scientific research articles. One person at each table said “Berkeley” at exactly the same time.

I drafted a letter about a possible job to a friend who’d recently been hired at Rolling Stone—possibly the most pathetic job-hunting letter ever written, although I've had a few nearly its equal. “I need money, but I’m not up for another long-term suicide mission like the Phoenix.” I revised it a few times but to no avail.

In November, I looked out “into the blue twilight of Columbia Street on Thanksgiving afternoon. Little traffic, a few people in the street. Bare branches, old houses; it is, in repose, a European street.” In fact even more international—along its lengths were new residents like the Portuguese speakers, holdover Irish, Jamaicans, educated young whites still experimenting and living on the margins.

|

| me and my shadow. Photo by Paula Rhodes |

On the mantle photos of my mother and sisters, a Gino Severini card, a program from my college play. In the study, two photos of me—one as a small boy, one in college, both with the same gesture; a Marx Brother poster with an Einstein photo interposed as the fourth brother, photos of Catherine Deneuve, Truffaut, Vanessa Redgrave. “Books, colors, music, some furry animals, some food in the kitchen and a tub for hot baths. My home.”

“I understand what I have to do,” I wrote. “Pay my bills to keep my blue rooms, the nice heat, the nice hot water, the electricity for the music, the nice food. I will be commercial. I will be journalistic. I will be a cross of myself and a fox.”

No comments:

Post a Comment