Television and I grew up together. This is our story. Latest in a series.

When network television first blossomed in 1950, one of its first and most popular forms for evening programming was the variety show. From a technical standpoint, variety shows were essentially a series of live performances on a stage, with plenty of room for large television cameras and predictable lighting, and so they were within the capabilities of early television production.

But they were also heirs to entertainment forms that go back through American and world history. Simply from the past half century, they had strong connections to radio shows, stage revues, vaudeville, burlesque, nightclub, Borscht Belt summer hotel entertainments and beyond, with elements of pantomime and the circus. Moreover, the first TV variety shows featured performers who learned their craft and developed their stage identities in several of these venues. They embodied that entertainment history.

For instance, Jimmy Durante, who by 1950 had been an entertainment star for some thirty years. He was so famous that well-known writer Gene Fowler wrote his biography in 1951, titled Schnozzola. In typical New York style of the time, the word referring to Durante’s trademark big nose combines Yiddish and Italian.The son of Italian immigrants, Jimmy Durante was born in the Bronx in 1893. The woman who would become his mother had arrived from Salerno the very day that the Statue of Liberty was officially unveiled in New York Harbor, in October 1886. His father had emigrated a few years earlier, also from Solerno, beginning in America as a laborer before earning enough to open a barber shop, the trade he had trained for in Italy.

Jimmy Durante started piano lessons in eighth grade—the last year of formal schooling he completed—with his sights already set on the latest rage of ragtime. His first gig was on Coney Island in 1910. Next he played at a rowdy Chinatown club where Irving Berlin once worked. A summer gig at a club back on Coney Island had him paired up with a hyperactive young singer, Eddie Cantor. He played all night in some 20 similar venues where he became known as Ragtime Jimmy.By 1917 ragtime was morphing into jazz, namely the Dixieland coming up from New Orleans. Durante brought four players from there to New York and formed Jimmy Durante’s New Orleans Jazz Band. On some numbers he stood up at the piano and joked with the band, adding another characteristic to his reputation.

By the early 20s he became part owner of his first night spot, the Durant Club. Soon he was partnering with singer Eddie Jackson and dancer Lou Clayton. Besides music, comic banter and skits became part of the act, all at a frenetic high-spirited pace. They were an immediate hit, as was the club in Prohibition New York, with customers that included the chronicler of the milieu, Damon Runyon, and George M. Cohan as well as the top politicians and gangsters of the day.Though vaudeville circuits traveled to many cities and towns, the capital of vaudeville was New York. By the late 20s, the team of Clayton, Jackson and Durante were hit performers on Manhattan’s top vaudeville stages. The vaudeville equivalent of Carnegie Hall was the Palace theatre, and playing the Palace was the vaudevillian’s dream. Durante and company not only played the Palace—in their first week they broke its attendance records.

_1.jpg) |

| Buster Keaton, Thelma Todd and Durante in 1932 "Speaking Easily" |

From the evidence of 1959 recordings, Durante remained an accomplished and inventive pianist with his own style, but sitting at the keys became a decreasing part of his evolving act. He was more often on his feet, dancing and prancing in vaudeville stage style, or doing physical stunts and takes. Though the characters he played in movies weren’t too far removed from himself, he could act a convincing scene. His baggy, rumpled suits and slouch hat, his exasperated frown and emphasis on his substantial nose, all became his signature clown suit. All of this made him appealing for the visual medium of television.

Though based on his Bronx malapropisms, his club and Broadway patter and the lyrics to his songs were verbally sophisticated, while also being corny and surreal. There were often more words than notes as his verbal gymnastics and interplay with the band took precedence. All of this also made the transition to television, though in simplified form.Durante’s first TV gig was as one of the rotating hosts of the Four Star Revue (later changed to All Star Revue), broadcast on NBC beginning in 1950. The multiple hosts were standard in the first variety shows, though not all stuck with the format. Apparently the idea was to attract viewers who might want to see what the stars behind those radio voices looked like in action.

Durante hosted a total of 24 one hour shows over the first three seasons (on Saturday nights), before moving over to the more popular Colgate Comedy Hour, also on NBC (on Sunday nights.) Though he hosted only eight shows, they were seen by many more viewers—this was a highly watched show, and by 1954, a lot more families had TV sets. He then moved over to The Texaco Star Theatre, alternating for a season with Donald O’Connor, and then appearing weekly in his own Jimmy Durante Show through the 1955-56 season. In his early 60s, Jimmy Durante was a television star.

In many ways Durante’s appeal was unique. His style was one of a kind, and his personality seemed generous and genuine, especially when working with co-stars. (Frank Sinatra never looked happier than when he was working with Durante.) As occasionally happens, Durante actually was genuine and generous offstage as well. Gene Fowler refers to his “grotesque tenderness,” and estimates that he regularly gave away at least 40% of what he earned. But Durante was hardly alone in bringing a long resume in multiple performance venues to early TV variety shows. Milton Berle was a child actor in silent films before developing his skills as a vaudeville comic (which usually involved a little singing, dancing and acting as well), beginning at age 16. By the 1930s he was performing in nightclubs. He dabbled in movies but set his sights on radio in the 1940s. In 1948 he became one of the rotating hosts of Texaco Star Theatre, and quickly proved so popular that it became his show. He reproduced elements of his late 40s radio variety show, adding visual slapstick, cross-dressing and skits from vaudeville. He became the first major television star with adult audiences, dominating Tuesday nights, and earning the nickname of Mr. Television. As a teenager, Jackie Gleason was a carnival barker and half of double act for vaudeville theatres. In his 20s he played nightclubs as a comedian and acted in supporting roles in Hollywood movies. Like Berle, he was hired as one of several rotating hosts for a 1950 variety show, Cavalcade of Stars on the Dumont network, but soon transformed it into the Jackie Gleason Show. After transferring to CBS, his show became a hit of the mid-1950s.Such pedigrees were also common for acts on these shows. Some had even deeper roots. Popular 1950s guest star Buster Keaton was one of the original silent comedy geniuses (in his last 1930s films he partnered with Jimmy Durante). But his performing experience went back through vaudeville to one of the 19th century American theatrical forms, the medicine show-- entertainment off the back of a wagon to gather a crowd for the patent medicine pitch.

I emphasize this genealogy of the first TV variety shows and their hosts not mainly to make an historical point, but to suggest an element that made experiencing these shows as a viewer unique. When as a child I laughed at Milton Berle yelling “Makeup!” and getting hit in the face with a giant powder puff, it was new to me, but not to comedy performance. I didn’t notice anything particular about a song and dance number performed by guests Bob Hope and Jimmy Cagney. When I saw a typical finale to a Jimmy Durante show—a musical number in which he and his old partner Eddie Jackson strutted around in top hats, tapping canes on the floor, I vaguely knew I was seeing something “old-fashioned.” It turns out that in all cases what I was seeing was vaudeville bits done by former vaudevillians.What I didn’t realize or appreciate until much later that in watching these variety shows, I was seeing layers of entertainment that went back beyond the 20th century. Just as the early morning cartoons I watched provided an accidental history of animation, these variety shows were a living history, an experience largely inaccessible today. Perhaps only my generation of children had it, because we were young when television was young.

And I did watch them all—the variety shows. There were basically two kinds of hosts: singers or comedians. Most variety shows headlining singers were short-lived (though some, like the Nat King Cole Show were noble tries—in 1957 this half hour was the first TV variety show with a black host.) The major exceptions were the perennial Perry Como (1949 to 1966, with his annual Christmas shows that had begun in 1948 continuing through 1994) and Dinah Shore (1951 to 1963.) As a child I waited to hear Dinah Shore sing her “See the USA in your Chevrolet” song, and see her blow an exaggerated goodnight kiss. Even in the 60s, Perry Como was a favorite of my grandmother, so we all watched it at her house.There were variations on the form, such as “talent shows” from Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts to Ted Mack’s Original Amateur Hour (and local variations, like the Wilkins Amateur Hour in Pittsburgh, sponsored by Wilkins Jewelers: simulcast from the radio show, it was Pittsburgh’s first live television show.)

There were a few attempts at shows hosted by bandleaders (Bob Crosby, Freddy Martin, Russ Morgan, Guy Lombardo), but the only one that stuck was Lawrence Welk, who went on through rock and roll and the 60s without changing much. (Guy Lombardo did become part of TV history with his New Year’s Eve shows; for a generation he was an inevitable part of welcoming in the New Year.) Shows hosted by musicians in particular, but variety shows in general gave my generation knowledge of songs from the entire first half of the 20th century and a little from earlier--many of which are now thought of as the American Songbook.

The shows hosted by comics were the most enduring. The Colgate Comedy Hour may have been the first evening TV show I knew by name, and I waited earnestly for my favorite hosts: Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Abbott and Costello, and Jimmy Durante.

In this show or a later one, I was especially entranced by Durante’s closing song, always the same signature song, called simply “Goodnight,” to more or less the tune of “The Shiek of Araby.” As the ditty ends he gets up from the piano, takes a trenchcoat from the rack and puts it on, pauses at a door to say his indelible final line: “Goodnight Mrs. Calabash, wherever you are.” Then he walks through the door into darkness, guided by circular pools of light on the floor.It was a magical, mysterious moment. I wondered where he was going, where those lights would take him. Every time he appeared I waited to maybe find out who Mrs. Calabash was. No one ever did find out for sure. The two leading theories are that it was a pet name for his first (deceased) wife, or that it was a generic name for (in his daughter’s words) “all the lonely old ladies watching the show.”

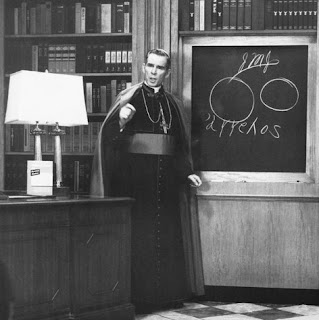

The first comic to establish the variety show as a network staple was Milton Berle, beginning in 1948. His Texaco Star Theatre set the vaudeville show example, with comedy, musical guests and dancers, as well as acrobats, ventriloquists (very big on early TV, with its close-up cameras) jugglers and so on. But Berle’s wild costumes, slapstick comedy and classic vaudeville/burlesque comedy skits were the main attraction. He was a national sensation, and was said to have sold more TV sets than any advertiser. He reigned for the first eight years of network TV. I watched Milton Berle on Tuesday nights, even at the risk of damnation for not choosing Bishop Sheen’s show on another station. Officially titled “Life is Worth Living,” it first ran on the fading Dumont network on Tuesdays, and then on another night on the fledgling ABC. It remains an anomaly in network TV—a Catholic priest standing in front of a blackboard in full regalia, delivering homilies for a half hour from a religious point of view. It was in that sense the anti-variety show. I did watch it sometimes, perhaps catching the second half of Berle, or in later years when it was on other nights. As a child, I was mystified by how Bishop Sheen’s blackboard was magically erased during his talk. (He referred to the “angels” that wiped it.) It says something about the innocence of the early 1950s audience that adults were similarly mystified by this simple camera move.I absorbed a great deal of vaudeville comedy style from Milton Berle, in particular the many variations on the double take. (Also of course the spit take.) He may have also been the first adult I saw who seemed to be having fun. Berle’s most direct TV heir was probably Red Skelton—I watched his show but wasn’t crazy about it. Skelton had perhaps the deepest resume of the major comics—he had played medicine shows, burlesque, vaudeville (at times doing pantomime) and nightclubs before radio and the movies.

Jackie Gleason’s show also followed but also developed the vaudeville variety format. The June Taylor Dancers were a regular feature, often shot from above in Busby Berkeley style. He participated in big production numbers with his nimble big man dancing (and it was at the end of one of these that he fell and broke his leg, necessitating his absence for a number of shows.) But his character driven skits with a series of repeated characters evolved beyond vaudeville set pieces into what became situation comedy, especially with the famous Honeymooners segment, that also became a stand-alone series for a season. He’s best remembered now for his catch-phrases (“And away we go!” etc.) and his Ralph Cramden character in The Honeymooners. Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows and subsequent incarnations also developed beyond the simple variety format (though it presented many singers, dancers and other acts) to become a kind of rep company comedy hour. It remains unique in the sophisticated subjects of its humor, such as foreign films that were generally available only in New York and a few other big cities.Some of its skits are still seen on film and are still hilarious. The show is also remembered for the lineup of its writing staff, which included Mel Brooks, Neil Simon, Woody Allen, Carl Reiner, Lucille Kallen and eventually Larry Gelbart. The physical and verbal comedy genius who made it all work was Sid Caesar, who invented his “double-talk” in foreign languages while waiting tables as a boy in his parents’ luncheonette, and watched variety performers as a saxophonist for a Borscht Belt orchestra before creating and performing in musical comedy revues in the Coast Guard during World War II. His TV partner Imogene Coca was also a physically gifted comedienne. (Nanette Fabray proved herself adept at comedy as well in a later incarnation of the show.) Carl Reiner was the perfect straight man.

Meanwhile a new generation of entertainer was also taking the national TV stage. Ernie Kovacs was an actor and a radio DJ who gradually expanded into local and then national television. He entered the new field of late night with a show on the Dumont network in 1954. (He would later be Steve Allen’s principal fill-in host on The Tonight Show.) He had a network show from 1952 through 1956, during which he experimented with camera tricks, exploring the visual possibilities of television more than other variety show comics. By the time of his series in 1962 he was able to use videotape to further refine this approach. Meanwhile he created memorable characters and bits, and his reputation grew with the years. |

| Moore, Burnett and Kirby |

Steve Allen also started professionally as a radio DJ who soon began playing fewer records and doing more comedy. He brought his talents for comic invention, innovation and quick wit to television in 1950, eventually creating a late night show in New York which went national in 1954 as the Tonight Show, the first network late night show. He was performing for two hours a night live, 90 minutes of which were on the network. Most of today’s conventions of late night were his inventions.

Two years later, he added the hosting of a Sunday night variety show on NBC. Though it had the usual novelty acts, Allen showcased music, especially jazz, and often played piano with his musical guests. He was decidedly offbeat for network TV, interviewing writer Jack Kerouac and then playing a jazzy background to Kerouac reading from his writing.

|

| Louis Nye |

The Steve Allen Show was opposite the Sunday night ratings leader, and among the most popular shows in television. Formally called “The Toast of the Town,” it was a major anomaly: a network variety show hosted by neither singer nor comedian nor star of any kind, but a barely articulate newspaper columnist, Ed Sullivan.

At first people didn’t know what to make of it, and it was regularly trounced by the Colgate Comedy Hour. But by the mid-50s it was immensely popular, surviving the head-to-head with Steve Allen’s Sunday night show, and going on to become a television institution.

|

| Roxyettes on Sullivan 1953 |

For there was lots of variety on this variety show: tumblers, high-wire acts, jugglers (and jugglers on high wires), magicians, clowns and acrobats, and even animal acts, all reminiscent of the circus, if not actually appearing directly from one. There were singers of all styles with the latest hit record or from the newest or most popular Broadway show, and occasionally from the opera. No musical style was out of bounds, including classical, country and western, R& B and blues.

Dancers in all

combinations and styles, including ballet, and orchestras playing popular and

classical music. There were foreign

stars and ethnic acts (national dances and songs) and novelty acts. There were puppets, like the Italian puppet

Topo Gigio, and ventriloquists. There

were impressionists and comics of all kinds, including duos (Wayne and Schuster

most frequently.) For singers and comics in particular, appearing on Ed

Sullivan became the equivalent of playing the Palace in a previous generation:

the top. (This was parodied in the musical “Bye, Bye, Birdie” with a hymn-like

song extolling Ed Sullivan.)

Dancers in all

combinations and styles, including ballet, and orchestras playing popular and

classical music. There were foreign

stars and ethnic acts (national dances and songs) and novelty acts. There were puppets, like the Italian puppet

Topo Gigio, and ventriloquists. There

were impressionists and comics of all kinds, including duos (Wayne and Schuster

most frequently.) For singers and comics in particular, appearing on Ed

Sullivan became the equivalent of playing the Palace in a previous generation:

the top. (This was parodied in the musical “Bye, Bye, Birdie” with a hymn-like

song extolling Ed Sullivan.)

The variety extended to the guests of every ethnicity and race. Though it didn’t seem unusual to me at the time, Sullivan’s show is credited with showcasing a large number and variety of Black performers. (The Supremes alone appeared 17 times.) “As a Catholic, it was inevitable that I would despise intolerance,” he told a reporter, “because Catholics suffered more than their share of it.” This rings true as a 1950s position. I suspect it’s not so true today. And it is of course within the context of a century of entertainment segregation, and worse. Though Sullivan was perhaps more tainted by the racism of his time that he knew, it is also true that he supported Black entertainers, and in 1949 he organized the largest funeral in New York City history, for Bill "Bojangles" Robinson. Prominent celebrity attendees included Milton Berle and Jimmy Durante.

I much preferred the Steve Allen Show for as long as it lasted, and I found it difficult to watch the Sullivan show straight through. But come Sunday night, the television was on, and so was Ed, and there was usually something worth watching. (Especially when it was either that or homework, or bed.)

The Ed Sullivan Show became the longest running variety show in TV history, lasting from 1948 to 1971. When it was cancelled, Sullivan was quoted as saying that vaudeville had died a second death.Even in the mid-50s, the technology to make television shows was improving, as was the quality of television sets to receive them. Program budgets were also increasing, so a range of programs became possible beyond pointing cameras at live performances on a stage.

At the same time, audiences were changing, or at least their circumstances, economic and otherwise. According to scholars, it was no coincidence that the rise of vaudeville coincided with the flood of immigrants, particularly into New York and other cities. The mill workers and service workers of the immigrant families in the city were vaudeville’s principal audience, and it is from immigrant families that most vaudeville performers came. To a large degree the same was true of early television, particularly the variety shows. But television was to reflect the changes in its audience as the 1950s went on, particularly in the form that in part also emerged from vaudeville roots: the situation comedy. Next time.

No comments:

Post a Comment