My intuition and intelligence both told me that Daniel Kahneman and his Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow are largely bullshit. I based this view on its oversimplifying and overreaching (all of which are habitual in behavioral psychology) as well as methodological lapses that even I could see, confirmed and elaborated on by the eminent psychologist Jerome Kagan.

But what I didn't realize was the immense influence of Kahneman and his analysis on major institutions, especially on the Internet, that ultimately may have decided the 2016 elections.

These revelations (to me anyway) came in a penetrating review by Tasmin Shaw of a new highly laudatory and uncritical book on Kahneman and friend, published in the New York Review of Books. It leads quickly into the Orwellian world of yet another ultra conservative billionaire and apparently the only thing that unites Bannon and Kushner, the Cambridge Analytica firm that claims to have essentially elected our Homemade Hitler.

Kahneman became famous among economists for his insight that, contrary to classical market economic dogma, people do not rationally choose to spend their money in ways most advantageous to themselves, but let emotional factors override their calculations. Incredible insight! Even though this is the very foundation of advertising, and that the heart or appetites winning out over the head with tragic and comic consequences is the theme of countless novels, plays, folk tales and myths over centuries. Amazing! Give that man a Nobel Prize! (They did.)

But his current fame is based on his binary worldview of human decisionmaking, between the fast (irrational, cf. emotion and intuition) and the slow (rational, meaning in his terms, doing the math.) His theory exemplifies its conclusions, in that it is easier to manipulate communication if you know what your audience wants to hear and you present it to them in an appealing way, such as a very simple theory that gratifyingly explains everything with just two cute and easy- to- remember choices.

But he did produce some math, and together with massive data collection, it did help create algorithms and some less than savory techniques to manipulate choices by going directly to emotions, used with alacrity by Amazon and Facebook, among others.

Though the Obama administration made some use of some offshoots of this behaviorial psychology model, Shaw writes, actual political manipulation is claimed for the far right consulting group Cambridge Analytica that cut its teeth proudly manipulating elections in the third world, then may well have worked for the most reactionary Brexit advocates, then definitely did work for our apprentice dictator, and may still be doing so.

Some of the techniques and the Cambridge A. connections to billionaire Robert Mercer and the White House are chillingly described in this Guardian article. Here again there are Russian connections--like the zombie websites waiting for the trigger word--and there may be more, if indeed Russian agents stole voter registration data and passed it on through the R campaign to political micro-message manipulators like Cambridge A.

Some dispute its effectiveness, Shaw writes. "But this doesn’t mean that there is no threat to democracy once we start relying less on information that can be critically scrutinized in favor of unconscious manipulation." That manipulation may include actually subconscious phenomena, Shaw suggests, through the use of what used to be called subliminal advertising--for example, emojs flashing on web sites too fast to be consciously seen.

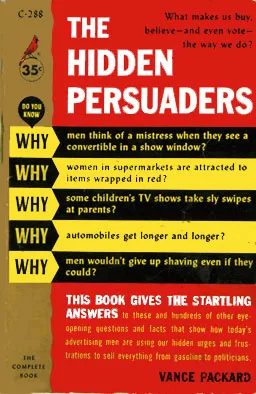

All this is at least as old as Vance Packard and The Hidden Persuaders in the 1950s, but its now on computational and electronic steroids. There is perhaps an irony in that Kahneman began by advocating for the rational side. But, as Shaw writes: "The two-systems view has managed to lend the appearance of legitimacy to techniques that might otherwise appear coercive."

Shaw states his own rejection of the Kahneman model:

"Psychologists have not yet uncovered the fundamental mechanisms governing human thought or finally found the secret key to mind control. Since the human mind is not straightforwardly a mechanism (or we are at least far from proving that it is) and its workings are unfathomably complex so far, they may never succeed in that venture. Some of the biases they have identified can easily be redescribed in ways that don’t make them seem like irrational biases at all; some are not transferable across different environments. The fundamental assumption of two discreet systems cannot be sustained."

But--Shaw warns:"this does not mean we can disregard the propaganda initiatives derived from Kahneman and Tversky’s work," especially when wedded with the global influence of the Internet and the power of Big Data. Big Data magnifies Big Lies.

Shaw's conclusion is glum: "It is still possible to envisage behavioral science playing a part in the great social experiment of providing the kind of public education that nurtures the critical faculties of everyone in our society. But the pressures to exploit irrationalities rather than eliminate them are great and the chaos caused by competition to exploit them is perhaps already too intractable for us to rein in."

The only hope in that regard lies in Kahneman's basic mistake: his fast and slow division, which distorts the nature of both intuition and intelligence. Actual intuition and intelligence enable us to see patterns (so for example that Homemade Hitler's moronic soundbite speeches finally make sense as crude recitations of the keywords identified in this research as triggers for a selected audience.) And they also enable us to take charge of changing our own minds--a topic I hope to go into here soon.

Origins: The Winter Solstice

-

The Winter Solstice is considered the most celebrated annual event in the

history of human cultures around the world. Ancient structures survive in

m...

1 week ago

No comments:

Post a Comment