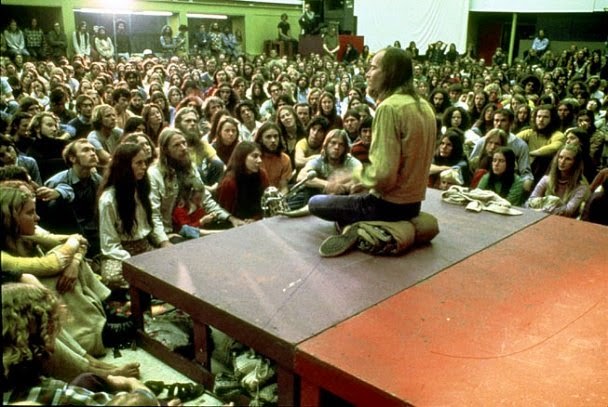

I'll start with someone few have heard of: Stephen Gaskin. I happened to be in Berkeley when his Monday Night Class at the Family Dog ballroom in San Francisco was packing in 1500 or so seekers in 1969. It culminated in those months in the First Annual Holy Man Jam, at which I was ordained a minister in the Universal Life Church by means of a scroll conferred upon me with the holy word Zap! and a toke on the world's longest bong.

Great days. As Gaskin, always wise, wisely said more recently, "You’ve got to be a rich country to have hippies. They’re a free, privileged scholar class that can study what they want. They’re like young princelings. That’s why the only other places to have produced hippies are countries like Germany, because they’re rich enough. It’s really been an upscale movement, in a way, except for when it broke through. And when it broke through was when it was the most revolutionary and really scared the Establishment, because hippies bond across cultural, religious, and class lines."

Above is what Gaskin looked like at the time of the Monday Night Class. I have a couple of books that preserve some of what he said, and one of the last surviving magazines to keep faith with that era's best instincts, The Sun Magazine, printed an excerpt with Gaskin's pretty recent commentary, as part of a project to annotate and republish these old volumes.

Shortly after the Holy Man Jam he left the Bay area and started a particular kind of commune called The Farm which he talks about in The Sun interview from the mid 1980s. He remained an activist, speaker and widely admired man. This photo is from 2009.

The Maestro. No writer in my lifetime made as many people happy reading his work, particularly A Hundred Years of Solitude. I saw the same joyful look on the faces of literary editor Ted Solataroff and the casual readers who read it on my recommendation. He remains an heroic example. In this click-happy age, his words are even more powerful: "Some say the novel is dead. But it is not the novel. It is they who are dead." His work and his spirit are immortal.

This photo from the New Yorker says everything I want to say about Mike Nichols. He was the most approachable yet incisive interpreter of our age, from the 1950s of Nichols and May to the 1960s of The Graduate to the 1970s of Carnal Knowledge to 1980s of Working Girl to the 90s of Regarding Henry and beyond. He brought both Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and Angels in America to the screen. He was the medium cool of New York. Though I never met him, I'll remember him for one week in 1984 when I saw two new plays he directed on Broadway: Tom Stoppard's The Real Thing and David Rabe's Hurlyburly. There haven't been too many years on Broadway like that since. He had discernment and taste, and his gift was witty and accessible presentation. He was the perfect host.

The closest I got to Ruby Dee was at the Pittsburgh airport, when she and Ossie Davis were paged, but unfortunately they didn't come to the white courtesy telephone nearest me. She was a familiar figure in the performing arts and in the public sphere from the 60s on, and by the 80s and 90s she was revered.

But long before that she began breaking barriers for black women especially, beginning when she was a young woman in the 1940s.

Robin Williams broke through the sitcom's mannered sterility in Mork & Mindy, and his frenzied humor remained to surprise and challenge the established forms. His hilarious genius in mating very different things is best expressed for me in his Elmer Fudd singing "Fire." But then in the movies he played Garp with a natural humanity that was equally surprising. Most of his film roles were like that. Thinking about him is to think hard about the vagaries and vicissitudes of life, of what we're given from birth, and how we use and handle them. There was a nobility about him, and a vulnerability too.

I once met a woman who had worked in Hollywood in the 40s who said that the romance between Bogart and Lauren Bacall was so smoldering that people from all over the lot came to watch the filming of To Have and Have Not. Bacall was magic on the screen in the 40s, and a strong presence in her films and plays thereafter. She lived beyond Hollywood, in circles that included writers and political figures. She made her mark on her times in positive ways. She was almost 90.

Peter Mathiessen wrote about his hard and extensive travels to places where few people were or go, and his face became the definition of weathered. He wrote books on Leonard Peltier and Indian Country that didn't help his career, and got deeply into Buddhism. His travel writings emphasized the ecological. All of which I relate to. He also wrote novels about a violent southern outlaw I couldn't relate to at all. His life and his writing were part of the same persistent quest and journey. Like the snow leopard he wrote about, he may have been among the last of his kind.

This is Mona Freeman in That Brennan Girl, released in 1946, the year I was born. She was never a movie star, and worked most of her career through the 50s and 60s in television series dramas, in supporting roles. She was a working actor, with another 40 years of life after her TV career. But in this 1946 role, she was the face of a generation, of hope and yearning, of the future. She stands in here for all the actors and others who did something that got their deaths mentioned in wikipedia or elsewhere, but who have been long forgotten. I want to honor them too. Maybe another stranger will see this photo, and remember her--or discover her.

I once met a woman who had worked in Hollywood in the 40s who said that the romance between Bogart and Lauren Bacall was so smoldering that people from all over the lot came to watch the filming of To Have and Have Not. Bacall was magic on the screen in the 40s, and a strong presence in her films and plays thereafter. She lived beyond Hollywood, in circles that included writers and political figures. She made her mark on her times in positive ways. She was almost 90.

Peter Mathiessen wrote about his hard and extensive travels to places where few people were or go, and his face became the definition of weathered. He wrote books on Leonard Peltier and Indian Country that didn't help his career, and got deeply into Buddhism. His travel writings emphasized the ecological. All of which I relate to. He also wrote novels about a violent southern outlaw I couldn't relate to at all. His life and his writing were part of the same persistent quest and journey. Like the snow leopard he wrote about, he may have been among the last of his kind.

This is Mona Freeman in That Brennan Girl, released in 1946, the year I was born. She was never a movie star, and worked most of her career through the 50s and 60s in television series dramas, in supporting roles. She was a working actor, with another 40 years of life after her TV career. But in this 1946 role, she was the face of a generation, of hope and yearning, of the future. She stands in here for all the actors and others who did something that got their deaths mentioned in wikipedia or elsewhere, but who have been long forgotten. I want to honor them too. Maybe another stranger will see this photo, and remember her--or discover her.

No comments:

Post a Comment